_resources1_16a08521505_medium.jpg)

Goncalo Mabunda from Mozambique and Syrian Fadi Attoura have experienced the trauma of conflict in their countries. But rather than expressing anger and grief through their work, the two artists prefer to use their art to transform memories of war into symbols of hope and to look beyond the darkness for a brighter future.

Mabunda uses weapons recovered after his country’s long civil war to create thought-provoking sculptures that comment on contemporary Mozambican society. He is presenting a series of new works in Dubai in a show organised by AKKA project, titled Game of Thrones. Attoura takes inspiration from his children and his own childhood memories to create playful and profound paintings that convey joy and hope. He is showing his latest body of work in Dubai in a show curated by Fann a Porter, titled A Playful Path.

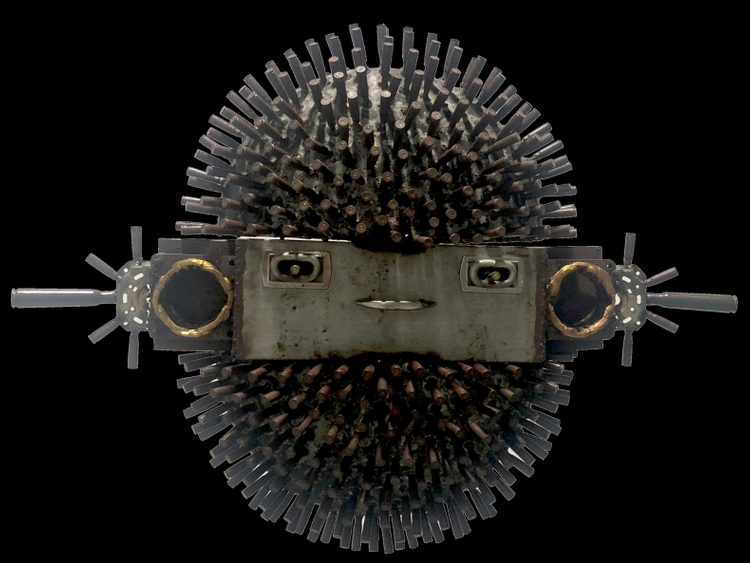

Mabunda was born in Mozambique in 1975, two years before the 16-year long war broke out. He plays with the weapons that terrified him in his childhood, giving them a new life as meaningful artworks. In his creative hands, parts of AK-47 rifles and Kalashnikovs, rockets, pistols, bullets, cartridges, magazines, bombs and grenades are transformed into majestic thrones, prehistoric animals with giant wings and legs, anthropomorphic robots, and expressive masks. He is internationally recognised for his unique style and has exhibited his work at the Venice Biennale, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and other prestigious venues.

“After the war ended in 1992, a religious organisation in Maputo encouraged the fighters to surrender their weapons in exchange for tools that could help them to earn a decent livelihood. The organisation then invited artists to find creative ways to use the weapons they had recovered and deactivated. Since I was already working with metal, it was easy technically, but emotionally it was quite disturbing. I continued working with this material because it helps me to portray the collective memory of Mozambicans and encourage peace. My sculptures force the viewer to physically face the weapons that were used in the war while also conveying the message that things can change and that objects of violence can be transformed into something positive and beautiful. To me these reworked weapons represent the resilience and creativity of African civilian societies,” Mabunda says.

My sculptures force the viewer to physically face the weapons that were used in the war while also conveying the message that things can change and that objects of violence can be transformed into something positive and beautiful.

The artist is showing two thrones and a series of masks made from decommissioned arms and pieces of scrap metal such as bicycle parts, old pipes and filing cabinets.

“I create thrones and masks because although my work is contemporary and universal, I want it to incorporate Mozambican and African traditions. In Africa, thrones function as traditional tribal symbols, ethnic art pieces and representations of power. My thrones made from weapons allude to the wars started by ruthless African leaders to capture power and cling on to it. My masks are inspired by African carved masks, but by representing both Western Modernism and African tradition through my pieces, I try to find an aesthetic and artistic way to unite cultures, and strip guns of the power to destroy and divide people. I have given them titles such as The Owner of the Two Me, The Architect of Marabenta, The Protector of the Refugees and The Singer of the New Language because they highlight issues such as the materialistic and selfish attitude of people today, the loss of traditional African culture, architecture and language due to Western colonial influences, and global issues of migration and the search for identity,” Mabunda says.

Attoura was born in 1978 in Hama, Syria where he still lives. He is well known for his minimalist paintings as well as for his work as a director and story board artist on Arabic television serials such as Nadour wa Nathour and Rijal Sadaqu. He draws inspiration from the toys and drawings of his children as well as from happy memories of his own childhood to create paintings that blend a carefree, childlike spirit with the formalism of Optical art.

The artist is fascinated by the mosaics of early Islamic art. These were first used in Mesopotamia in the third Millennium BC to decorate palaces and other important buildings and can be seen in ancient Islamic religious buildings such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. He has taken inspiration from the geometric forms and motifs of the mosaics to develop the grids and patterns that create depth and the illusion of movement in his Op art paintings.

On this pulsating background, Attoura has painted figures of cheerful children engaged in fun activities such as a game of hop scotch, swimming or riding bicycles. He has employed various visual techniques such as painting multiple figures or shadows, expanding and contracting lines, and contrasting colours to suggest movement, the passage of time and a three-dimensional feel in his compositions.

'Hope' for the viewer

For instance, My Angel features a woman with four hands holding three restless toddlers, which could be a way of showing just one lively child moving around; and in Knight, the multiple shadows behind the child on a rocking horse indicate the rocking movement.

The show also includes a series of paintings titled Hope. Here, Attoura has depicted a group of children, or perhaps one child at different moments in time, finding their way out of difficult situations such as climbing out of a deep tunnel or negotiating an endless maze-like staircase. The colourful pinwheels and flowers in their hands signify playfulness and positivity.

“The stained-glass windows and mosaic flooring I see in traditional Arabian homes all around my city inspired me to experiment with Op art. Living in Syria during the conflict was difficult. We could not leave our homes for long periods, so the children of my city were deprived of simple pleasures like playing outdoors. I found myself painting memories of my own childhood because I felt that it was joyous and beautiful unlike that of my children,” the artist says.

“I paint children because they represent innocence, purity, goodness, vitality and hope. They help me and my viewers to escape from the harsh realities around us and visualise a better tomorrow. I want to express the hope that my children and all the children of the world have a beautiful life, far away from wars and that they always walk on the playful path of fun, which is the best path for a bright future,” he adds.

Jyoti Kalsi is an arts-enthusiast based in Dubai.

Don't miss it: A Playful Path will run at The Workshop, off Al Wasl Road, Jumeirah, until December 7.

Game of Thrones will run at Akka Project’s pop-up space in Warehouse 60, Alserkal Avenue, until December 6.