Even ‘healthy’ superfoods can carry salmonella: UAE doctors explain the risks and how to stay safe

Low-moisture food can quietly carry the bacteria for a long time

Food poisoning takes many forms. A problem of undercooked chicken, dodgy street food, or maybe an unkempt kitchen. It doesn’t quite fit with the image of chia seed smoothies, artisanal chocolate bars, or carefully sourced 'clean' ingredients that dominate modern diets. Yet recent salmonella outbreaks linked to foods often perceived as wholesome have exposed a more uncomfortable truth: contamination doesn’t care about labels, trends, or wellness claims.

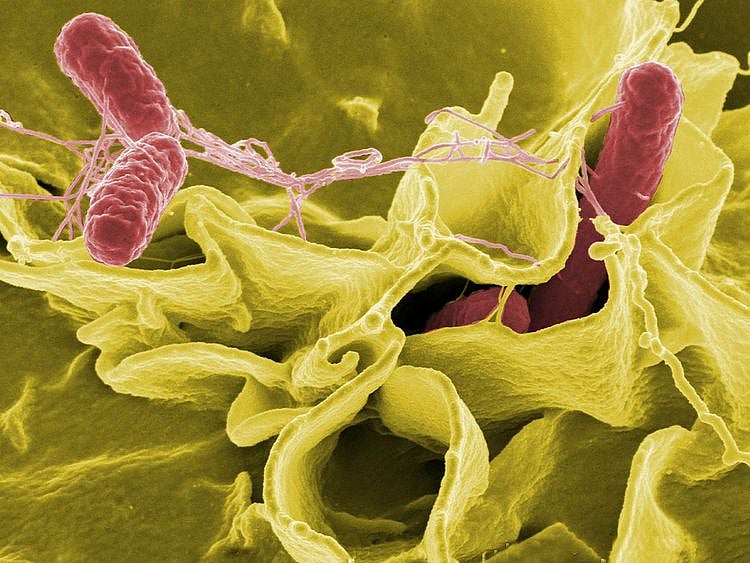

At its core, salmonella remains one of the most common and underestimated foodborne threats worldwide. It is a bacteria that causes food poisoning and is usually contracted through contaminated food or water, as Dr Sandeep Sharma, Specialist Gastroenterology of Medcare Hospital, Shaikh Saqr Al Qasimi Sharjah, explains. Once it works its way into the gut, it can trigger diarrhoea, stomach cramps, fever, nausea and vomiting. “Most healthy people recover on their own within a few days, but some people can get quite sick.”

That 'some people' is where the story becomes more complex and far more serious.

When ‘natural’ doesn’t mean safe

In recent years, outbreaks linked to seeds, nuts and chocolate have raised uncomfortable questions about superfoods. From an alternative medicine and functional health perspective, Dr Sharma points to the way these foods are produced as a potential vulnerability.

According to him, 'superfoods' are usually natural and minimally processed. Foods like chia seeds, raw cacao, or artisanal chocolate often skip aggressive heat treatments and chemical sanitisers to preserve nutrients. That’s good from a nutritional sense, but it also means there’s less killing of harmful bacteria if contamination happens.

In other words, the very processes that make these foods attractive to health-conscious consumers can also allow pathogens to survive quietly, without detection.

Dr Sharma adds that production methods matter deeply: “These foods are often grown in small-scale or organic systems, where soil health, compost, and natural fertilisers are emphasised. If those systems aren’t tightly controlled, bacteria from soil, animals, or water can persist.”

The final misconception, he says, is equating 'clean' with 'safe': “In short, ‘natural’ doesn’t automatically mean sterile and low-moisture foods can quietly carry bacteria for a long time without obvious spoilage.”

Clinical dietician Jaseera Maniparambil of Aster Clinic, Bur Dubai (AJMC), reinforces this point from a nutrition and food safety standpoint, offering a crucial clarification. “‘Superfoods’ such as chia seeds, cacao, or artisanal chocolates are not inherently more dangerous than conventional foods. However, certain characteristics can make them more vulnerable to contamination if proper food safety controls are not followed.”

She explains why these foods deserve closer scrutiny: “Many superfoods are minimally processed and consumed without cooking, which means there is no heat step to kill bacteria like Salmonella. Seeds and nuts can become contaminated during drying or storage, and artisanal products may sometimes be produced in smaller facilities where industrial-level hygiene controls are limited.”

The takeaway, she stresses, is practical rather than alarmist: it is not whether a food is labelled a “superfood,” but how it is handled, stored and processed. “When good agricultural practices and strict hygiene standards are followed, these foods are just as safe as conventional products.”

A 2021 research article published in the Journal of Food Protection investigated Salmonella prevalence on seeds commonly consumed without cooking, including chia, amaranth and sesame. The researchers found that Salmonella was detected in a significant proportion of these seeds, and that it survived on them for long periods under typical storage conditions, highlighting a food safety risk for products eaten raw.

How contamination creeps in

One of the most persistent myths around foodborne illness is that contamination happens at a single 'bad' point, a dirty factory, a careless worker, or a one-off mistake. In reality, Salmonella’s journey is often far more fragmented.

Dr Sharma notes, “In real life, contamination rarely happens at just one step. It can start on the farm, from animal droppings, contaminated water, or soil. It can spread during harvesting, when equipment or hands aren’t clean.”

The bacteria’s resilience makes it particularly dangerous in dry products. “It can survive processing and packaging, especially in dry foods where bacteria aren’t killed. And finally, it can be reintroduced during transport, storage, or retail handling if good sanitation is not observed.”

Maniparambil echoes this layered risk, breaking down the supply chain vulnerabilities in clinical terms. Salmonella contamination can occur at multiple stages in the food supply chain.

She outlines them clearly, from farm-level exposure to contaminated soil, water, animal manure, or infected animals and birds, to processing failures when equipment, workers’ hands, or surfaces are not properly sanitized.

Even after production, the risk continues, during transport and storage, if foods are kept at unsafe temperatures or stored near raw animal products, and finally at the retail level, through cross-contamination between raw and ready-to-eat foods or improper handling by staff.

Her conclusion is blunt: “As contamination can happen at several points, food safety must be maintained at every step, from farm practices to refrigeration and hygiene in supermarkets.”

Why one person shrugs it off, another ends up hospitalised

Perhaps the most confusing aspect of Salmonella infections is how unevenly they affect people. Two people can eat the same contaminated food and experience entirely different outcomes.

It mostly comes down to the person and the dose of bacteria ingested. A healthy adult with a strong immune system who swallows a small amount of bacteria may only have mild symptoms, or none at all, Dr Sharma explains.

But for others, the consequences escalate quickly. Someone who is older, very young, pregnant, or immunocompromised may get ill. Certain strains of Salmonella are also more aggressive, and gut health, including natural bacteria and stomach acid, plays a key role in how the body responds.

Maniparambil expands on this with clinical precision, noting that the severity of Salmonella infection depends on several factors. These include immune strength, the amount of bacteria consumed, individual gut health and overall nutritional status.

As she explains, “Some people may only experience mild diarrhea, while others develop high fever, severe dehydration, or bloodstream infection, requiring hospitalisation.”

The aftermath few people talk about

For most patients, Salmonella is an unpleasant but temporary ordeal. However, both experts caution against assuming recovery always marks the end of the story.

Dr Sharma says, “Most people recover fully, however, some may develop joint pain or arthritis-like symptoms weeks later.” A small number go on to experience lingering bowel problems, such as bloating or irregular, ill-formed stools. Rarely, the bacteria can enter the bloodstream and cause more serious infections.

Maniparambil offers a similar warning. “Most people recover completely within a few days to a week. However, in some cases, long-term effects can occur.” These include reactive arthritis, irritable bowel–type symptoms, and in rare instances complications affecting the heart, bones or nervous system.

Can natural solutions help?

The rise of probiotics, plant antimicrobials and essential oils has fuelled interest in alternative ways to reduce the risk of foodborne illness. Dr Sharma acknowledges their potential, with important caveats.

“Probiotics can help crowd out harmful bacteria in the gut and reduce shedding of Salmonella,” he says. Laboratory studies have also shown promise: “Certain plant compounds and essential oils like oregano, thyme, or cinnamon, can inhibit Salmonella in lab studies.”

But he draws a clear line. “From a medical standpoint, these approaches work best as supportive tools, not stand-alone solutions. They don’t replace proper hygiene, sanitation, or heat treatment, but they may reduce risk when used responsibly.”

Ultimately, the most effective prevention remains unchanged: proper cooking, refrigeration, hand hygiene and avoiding cross-contamination.

Salmonella doesn’t discriminate between fast food and farmers’ markets, between processed meals and organic indulgences. The real risk lies not in the idea of 'superfoods,' but in forgetting that bacteria operate by biological rules, not branding. Clean eating may nourish the body, but only vigilance, hygiene and informed handling truly keep it safe.

Here's what can help:

Wash and rinse seeds, nuts, and superfoods before use.

Store dry foods in airtight containers, away from moisture.

Keep raw and ready-to-eat foods separate to avoid cross-contamination.

Follow proper refrigeration guidelines for perishable items.

Practice good hand and kitchen hygiene when handling foods.

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.