Dubai: With global food prices rising at the most rapid pace in a decade last year, the question on everyone’s minds is will it reflect in the cost of everyday groceries in the months to come?

With corn, wheat, soybeans, vegetable oils - which form the backbone of much of the world's diet - getting dramatically more expensive, alarm signals have been flashing for global shopping budgets.

World food prices jumped 28 per cent in 2021 to their highest level in a decade, and hopes for a return to more stable market conditions this year are slim, the UN’s food agency cautioned on Thursday.

This latest jump is being closely watched because staple crops are a ubiquitous influence on grocery shelves - from bread and pizza dough to meat and even soda.

The monthly figure eased slightly in December but had climbed for the previous four months in a row, reflecting harvest setbacks and strong demand over the past year. Higher food prices have contributed to a broader surge in inflation as economies recover from the coronavirus crisis.

In its latest update, the food agency was cautious about whether price pressures might abate this year.

“While normally high prices are expected to give way to increased production, the high cost of inputs, ongoing global pandemic and ever more uncertain climatic conditions leave little room for optimism about a return to more stable market conditions even in 2022,” Abdolreza Abbassian, senior economist at the UN’s food agency, said in a statement.

Should I be worried about food price inflation?

Soaring raw material prices have broad repercussions for households, and threaten a world economy trying to recover from the damage of the coronavirus pandemic.

Emerging markets, in some cases already under pressure from weaker currencies, are particularly vulnerable because food costs make up a larger share of their spending.

For the poorest and often politically unstable countries, the surge in raw materials threatens to further stoke global hunger.

What global inflation means for everyday prices

The surge in raw material prices has been stoking fears of a higher rise in inflation. The key question for analysts is whether the price increases will be short-lived or morph into long lasting, broader inflation worldwide.

Analysts mostly agree that global producer prices (prices received by producers for their output) will continue rising into the quarter ahead, but they are divided over whether the price surge will be transmitted to the consumer side.

The global economy's path out of the COVID-19 shock will be different from that of previous crises because of broad pent-up demand and different inflation dynamics, global asset manager BlackRock said in a recent report.

Moreover, rather than across-the-board inflation, price pressures are affecting different economic sectors unevenly.

But it can also be more narrowly calculated – for certain goods, such as food, or for services, such as a haircut, for example. Whatever the context, inflation represents how much more expensive the relevant set of goods and/or services has become over a certain period, most commonly a year.

Understanding how inflation is measured

Consumers’ cost of living depends on the prices of many goods and services and the share of each in the household budget.

To measure the average consumer’s cost of living, government agencies conduct household surveys to identify a basket of commonly purchased items and track over time the cost of purchasing this basket.

The cost of this basket at a given time expressed relative to a base year is the consumer price index (CPI), and the percentage change in the CPI over a certain period is consumer price inflation, the most widely used measure of inflation. (For example, if the base year CPI is 100 and the current CPI is 110, inflation is 10 per cent over the period.)

The CPI basket is mostly kept constant over time for consistency, but is tweaked occasionally to reflect changing consumption patterns – for example, to include new hi-tech goods and to replace items no longer widely purchased.

Food prices on the rise, but why?

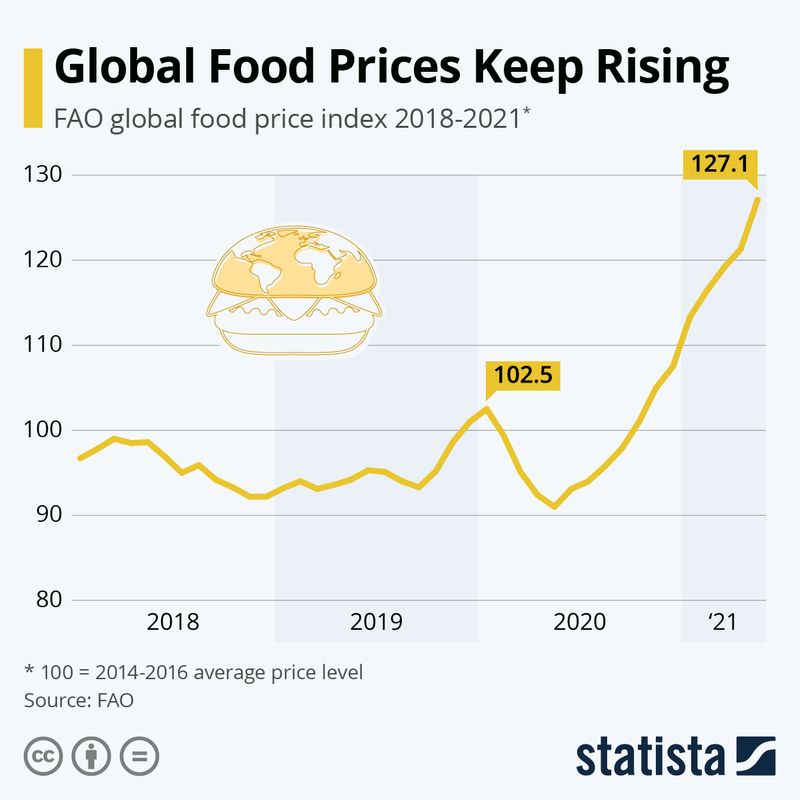

After the wholesale price of food initially slumped during the coronavirus pandemic, the global Food Price Index (FAO) has shown a steep increase, the World Economic Forum had revealed.

Most recently, food around the world was more than 27 per cent pricier than the 2014-2016 average, on which the index baseline of 100 points is calculated.

Palm oil prices have been driving the increase in the index since the fourth quarter of 2020, but global cereal prices also showed a significant bump in the past months, together creating a level of food prices not seen in a decade.

Dry weather and production disruptions due to COVID-19 coupled with high global demand led to the depletion of palm oil inventories, in turn driving up prices.

As transportation picked up again, biodiesel demand led to an increased need for soy oil. Both developments caused prices for vegetable oils to exceed the 2014-2016 average by almost 75 per cent in May last year.

“Speculation about whether the disruptions of the pandemic would drive up food prices have been abound, but due to the COVID-related economic downturn and falling out-of-house demand, they actually decreased at the start of 2020, reaching a low one year ago,” the World Economic Forum noted in their blog.

According to the UN, falling mineral oil prices also factored into the initial deterioration of food prices as many alternative fuels, which are made out of food stocks, saw demand fall.

Will UAE grocery prices rise as a result?

As soaring crop prices affect countries across the world, the UAE has been considering price controls on some foods.

The move from UAE, which imports 90 per cent of its food and allows its economy ministry to control prices, comes as several other countries worldwide have come under inflationary pressures.

Although we are in the peak of winter season, no noticeable changes in prices were observed, due to inflation or otherwise.

However, the prices do not differ starkly during most months of the year, as the government keeps a lid on costs and prevents any major price spikes from happening.

How to save money grocery shopping in Dubai

When studying prices over the last 17-plus months, Your Money has found that the cost of food items stayed largely in check. When analysing the cost of poultry, seafood, fruits and vegetables, there are useful patterns that can assist a shopper in saving money in both the short run and even more so in the longer term.

Which days are ideal for grocery discounts?

During the course of these months, it was observed to be cost effective to buy fresh chicken during the start of the week, especially on Mondays. On the other hand the cost of seafood and vegetables were seen to be largely cheaper halfway through the week, and cost effective fruits could be ideally picked up towards the end of the week.

Latest per-kilogram prices of chicken, every fish variant available in the market:

As of December 15, among fish variants, Seabass costs Dh44.8 per kilogram and Hamour was priced at Dh39.9. On the other hand, Kingfish was priced at Dh26, and Salmon was priced at Dh41.5. A kilo of SeaBream costs Dh35, while small-sized shrimp was currently cheaply priced at Dh28.

When it comes to the cost of a kilogram of poultry, the price of frozen chicken starts at Dh8.3, while fresh chicken has a minimum price of Dh13.3. Local medium-sized eggs are priced at Dh9 for 15 eggs.

Latest per-kilogram prices of every variant of beef and lamb available in the market:

The price of beef and lamb, be it variants from Australia, India, Pakistan was priced as follows, as of Wednesday.

Among different varieties of beef, the variant from Australia cost Dh39.5 per kilogram, the type from India was priced at Dh28.3 and the kind that was locally produced was Dh49. On the other hand, when it came to lamb, the Australian variant now costs Dh42.9, the breed from India was priced at Dh35, the Pakistani variety costs Dh37.7, while a kilogram of the regional variety was Dh45.2.

Latest per-kilogram prices of every variant of fruits and vegetables available in the market:

When it comes to fruits the per kilo starting price of bananas are currently priced at Dh5.1, oranges are Dh3.5 and apples cost Dh4.3. On the other hand, prices pertaining to vegetables include - regional tomatoes costing Dh4.7, red onions at Dh2, potatoes at Dh2.5 and lettuce at Dh5. Also, the price of a kilogram of lemon is Dh4, while lime costs Dh4.9.