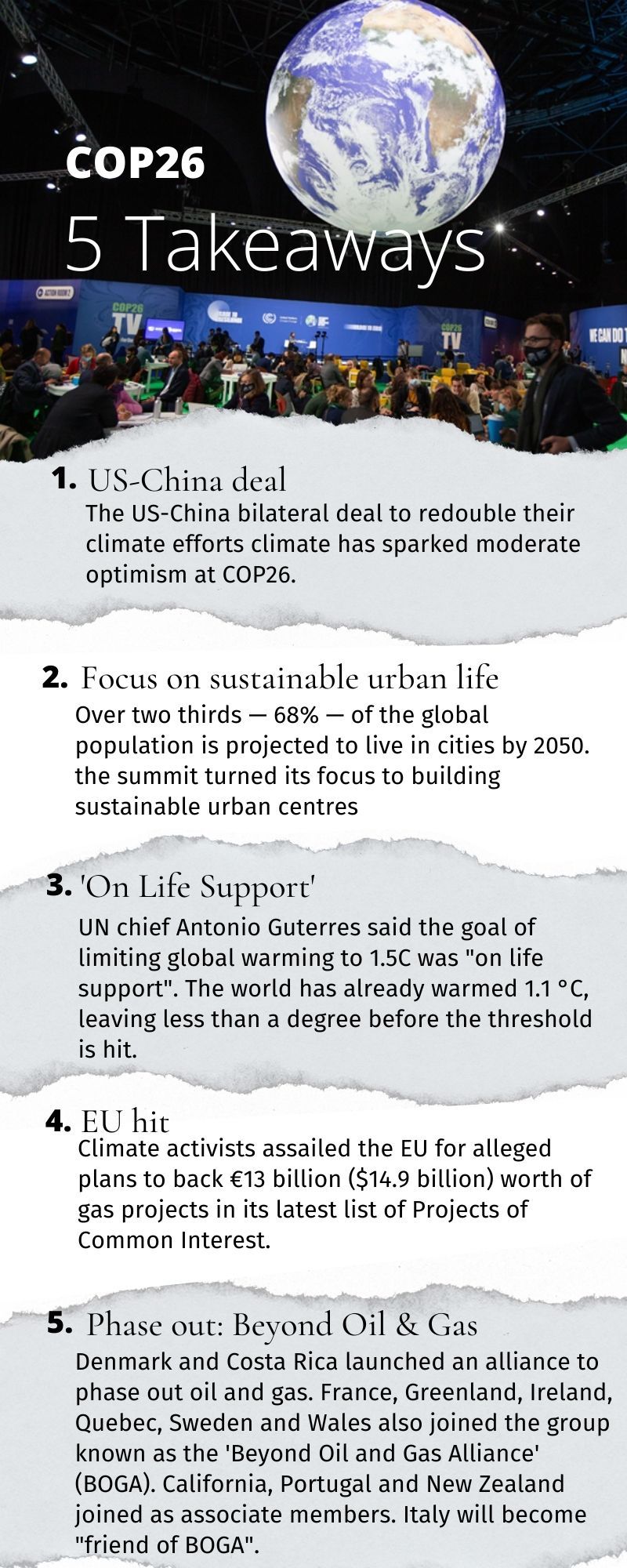

At the global summit that just wrapped up in Glasgow, known as COP26, Filipino lawyer Vicente “Vice” Paulo Yu III fought hard for the 134 developing countries under the G77 and China group during crucial climate change talks.

Originally from southern Philippine city of Davao, the 50-year-old father of two comes across as diplomatic and soft-spoken, yet clear-headed and firm.

At COP26, he coordinated the negotiating team for the G77 ((which includes countries from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, as well as India dn the Gulf nations) and China, specifically on loss-and-damage negotiations in the latest round of UN climate talks.

“We pushed hard and got that first chunk of the agreement last Saturday (November 6, 2021),” Vice told Gulf News.

From the outset, Vice has been bent towards issues that affect the common people. The Philippines- and US-educated lawyer has been a negotiator in the COP process for years, serving as an adviser to a number of developing country delegations (including the Philippines) and to the group. Vice is based in Geneva, where he lives with wife Genevieve and their two girls, Danielle Angelique, 14, and Gabrielle Victoria, 12.

Loss-and-damage negotiator

Specifically, he coordinated the negotiators of the Group of 77 and China on “loss and damage” issues at COP26. Early in his life, Vice took the side of marginalised communities affected by environmental disasters.

14

number of days of gritty negotiations by 20,000 diplomats from nearly 200 countries at COP26 (Oct. 31 - Nov. 12, 2021)While taking up law during evenings, he worked during the day for the Legal Rights Natural Resources Center, an NGO advocating for indigenous people’s rights. From July 2016-June 2018, Vice served as the Deputy Executive Director of the South Centre, the inter-governmental policy research institution of developing countries.

From July 2016-June 2018, Vice served as the Deputy Executive Director of the South Centre, the inter-governmental policy research institution of developing countries.

Advising governments

oday, his work includes the provision of technical policy and legal advice to developing country governments — especially on the right to development, international environmental law, development economics, international climate change policy.

Prior to joining the South Centre, he worked for Friends of the Earth International (FOEI); he was staff attorney and head for Research and Policy Development of the Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center (LRC) in the Philippines.

Education

Vice obtained his political science (with honours) and law degrees from the University of the Philippines. He completed his master of laws degree (with honours), specialising in international trade law and international environmental law from Georgetown University, where he was a Fulbright Scholar.

He also taught law at the University of the Philippines. He has also been a consultant for various UN agencies, providing research and training, and capacity-building services on development policy and on climate change issues.

Vice has published papers and articles on issues relating to trade and environment, energy, mining policy, sustainable development, climate change policies and cooperation among developing countries.

Interview excerpts:

Are you happy with the outcome of COP26?

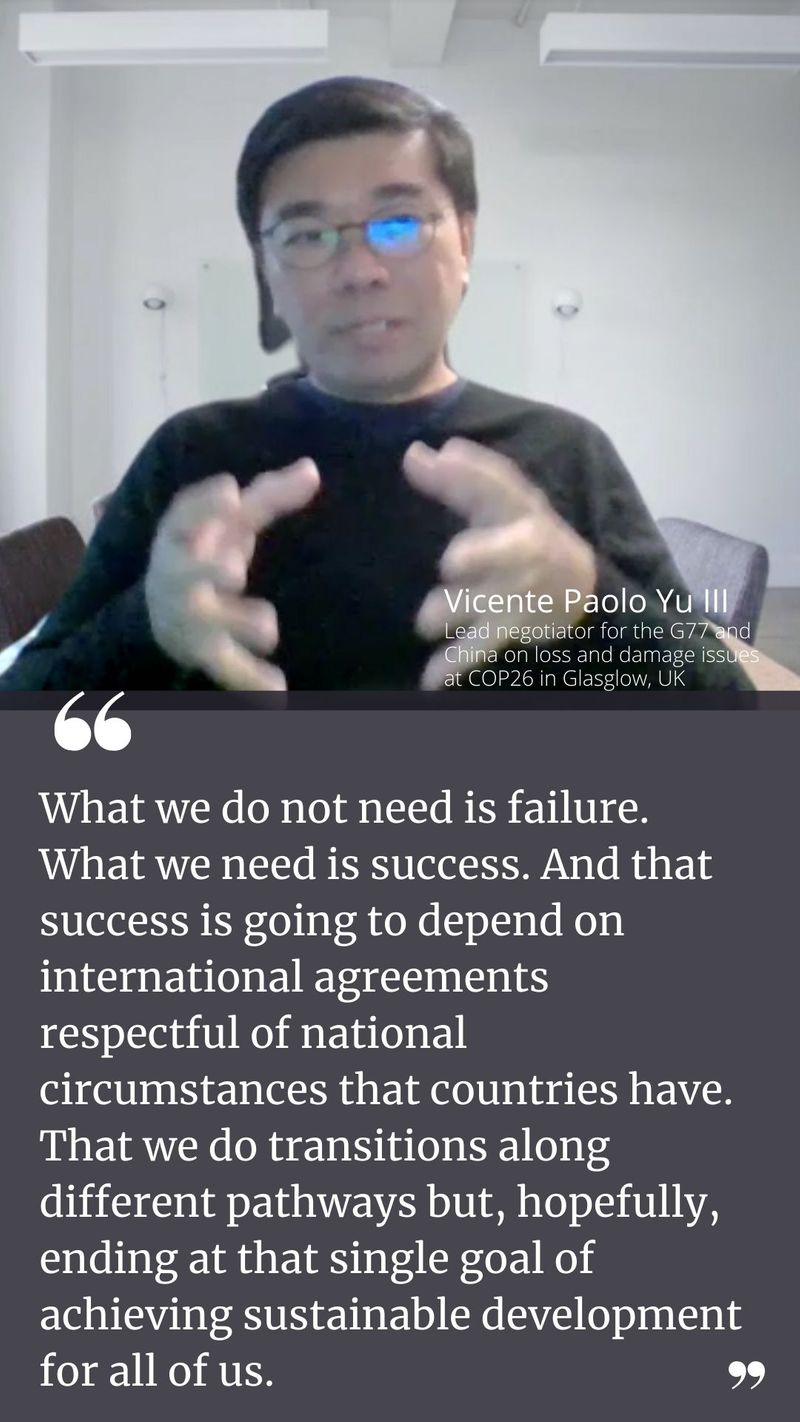

As a negotiator, I am happy with the outcomes we achieved in the loss and damage negotiations, although I am deeply aware that we still have a long road ahead of us. Before COP26, I think we started out with an expectation that it was going to be a long haul, that it was going to be very difficult process to get an agreement — on the functions (of the Santiago Network) and on having this idea of loss and damage.”

I’m happy in terms of having a clear idea now of how the Santiago Network would operate and what it would do —we have a clear idea of the functions that’s agreed across all of governments that were taking part in the negotiations.

We also have now an institutionalised recognition within the system — in the climate negotiations — by all governments, that the idea of increasing action and support, including finance, on loss and damage is a very, very important and central part of the conversation in terms of how we cooperate as governments on climate change. And I think that is a good outcome.

In terms of the overall balance of the package from COP26, I still have to read through the various decisions adopted to be able to assess whether we had real progress on the other issues.

What are the UN climate negotiations like under the COP mechanism?

The UN negotiation process is like skipping rope while trying to move forward. UN conferences like these do not progress in leaps and bounds. It’s not like a steeplechase where you jump past over the hurdles, nor is it like a pole vault, where you put a pole in the ground and jump straight over; nor is it a high jump. UN conferences like these are more like skipping rope, where you move forward bit by bit.”

Did you achieve what you set out to do?

At least for the loss-and-damage negotiations I was directly engaged in, yes, I think for developing countries who were really engaged in loss-and-damage negotiations, we achieved some progress when judged by the standards of UN conferences.

But of course, when judged by the standards of what we really need, in terms of what should have been done 10 years ago, we have not achieve enough, so we really need to do more. So much more.

What are the key challenges now?

And we need, in fact, to put more pressure and more advocacy into strengthening the loss-and-damage component of the international climate regime. If you have civil society, media, governments all over the world, indigenous communities, all other sectors coming in and saying ‘We need to get to a move on in loss and damage’, then that perhaps could actually make us go from skipping rope to maybe running the steeple chase.

The change in wording was made after a late intervention by China and India. But it remains the first time plans to reduce coal have been mentioned in such a climate deal.

Why is the loss-and-damage mechanism facility important? And is it a compensation?

We do not think of it as compensation, or as “payment” from developed countries to the developing world. We think of it more as another way in which international cooperation on climate change can be enhanced, or could be improved, under the Climate Convention and its Paris Agreement.

It’s not like we’re directly blaming the developed countries for creating the climate crisis, although if you look at it from the historical perspective, they were in fact responsible for the dominant part of the emissions that generated this whole climate crisis in the first place.

Developed countries were responsible for something like 80% of the total cumulative greenhouse gas emissions from human activity since the Industrial Revolution.

But it’s not because of this that we’re asking for this loss-and-damage finance facility. We’re asking for this because we see it as another plank in the broader international climate regime through which international cooperation can take place and everyone can do better in the fight against climate change.

What are these planks?

One: mitigation, or emission reductions. Cooperation on this is important.

Two: Adaptation, to help us prepare for climate change. Again, cooperation on this is important.

Three: Means of implementation. So this is the broader issue of finance and technology transfer from developed to developing countries. This is what will help developing countries do more on mitigation and adaptation.

And what we seeing is that on mitigation, not much was done over the last 25 years. On adaptation, the financing is rather small. On the delivery of climate finance obligations from the developed countries to developing countries, has not been sufficient.

All of these have created a multiplier effect in failing to slow down climate change. Which means the impacts of climate change are increasing, and which means the loss and damage on our countries are increasing.

We know that all of these three planks are not sufficient for now, and if we know that loss and damage will come into play, then we also need to have another financing scheme into that. That’s the reason why aside from setting up the Warsaw International Mechanism, then the Santiago Network, we also want this loss and damage financing facility, to prepare us better. To future-proof us from climate-related loss and damage.

So it’s not compensation. It’s really more about international cooperation.

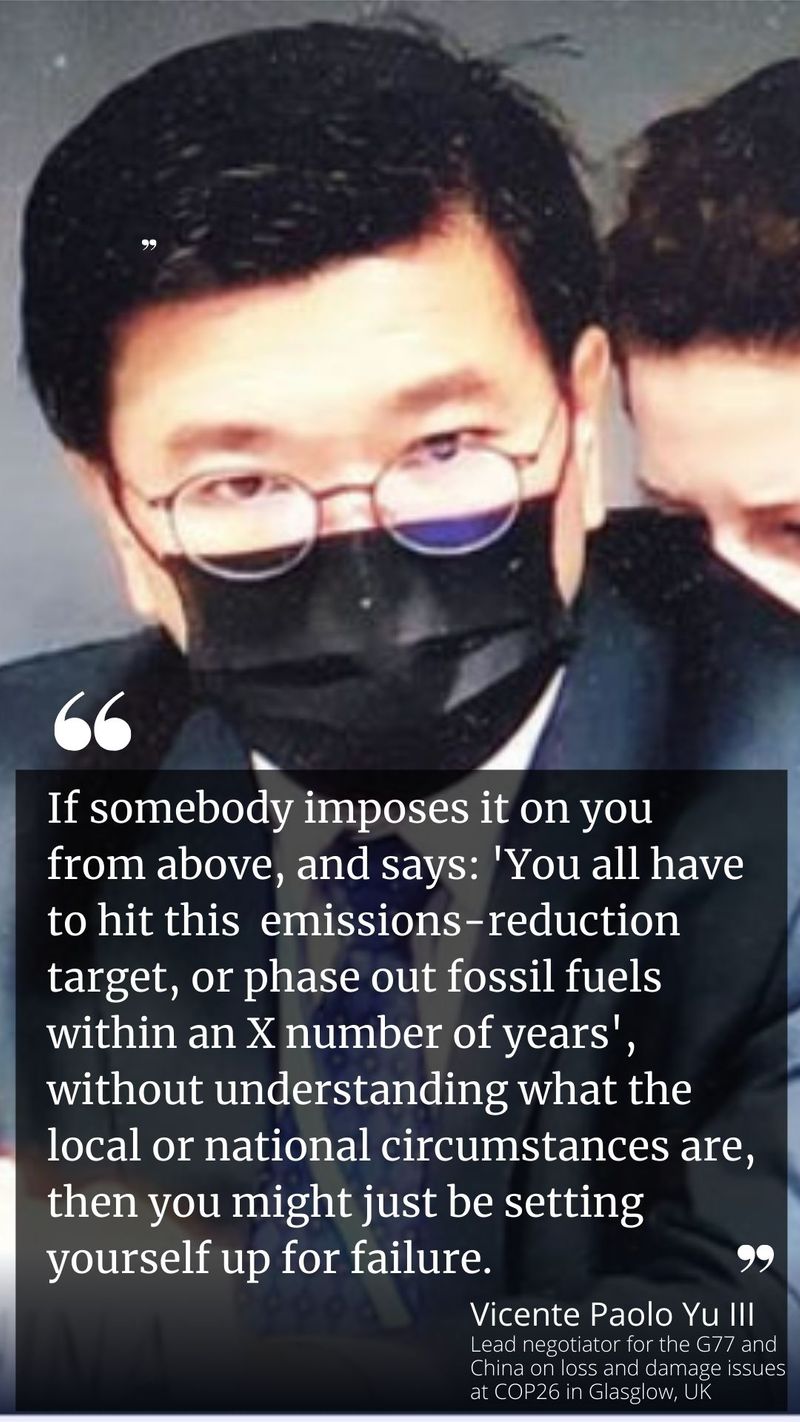

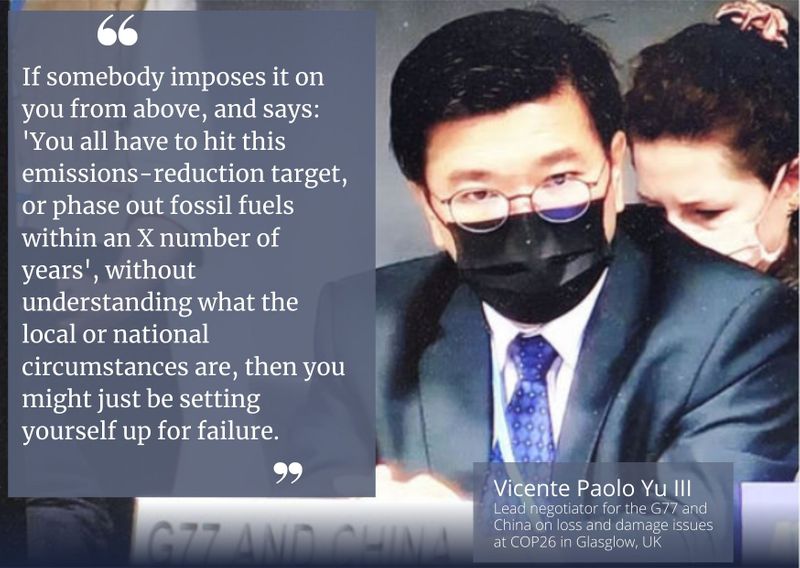

What were main the objections of Indian and China?

The international media reported the both China and India had asked for the language on fossil fuels to be more nuanced in the final text of the summit’s document.

India and China were concerned about the wordings specifically about ‘phaseout of unabated coal, and inefficient fuel subsidies’.

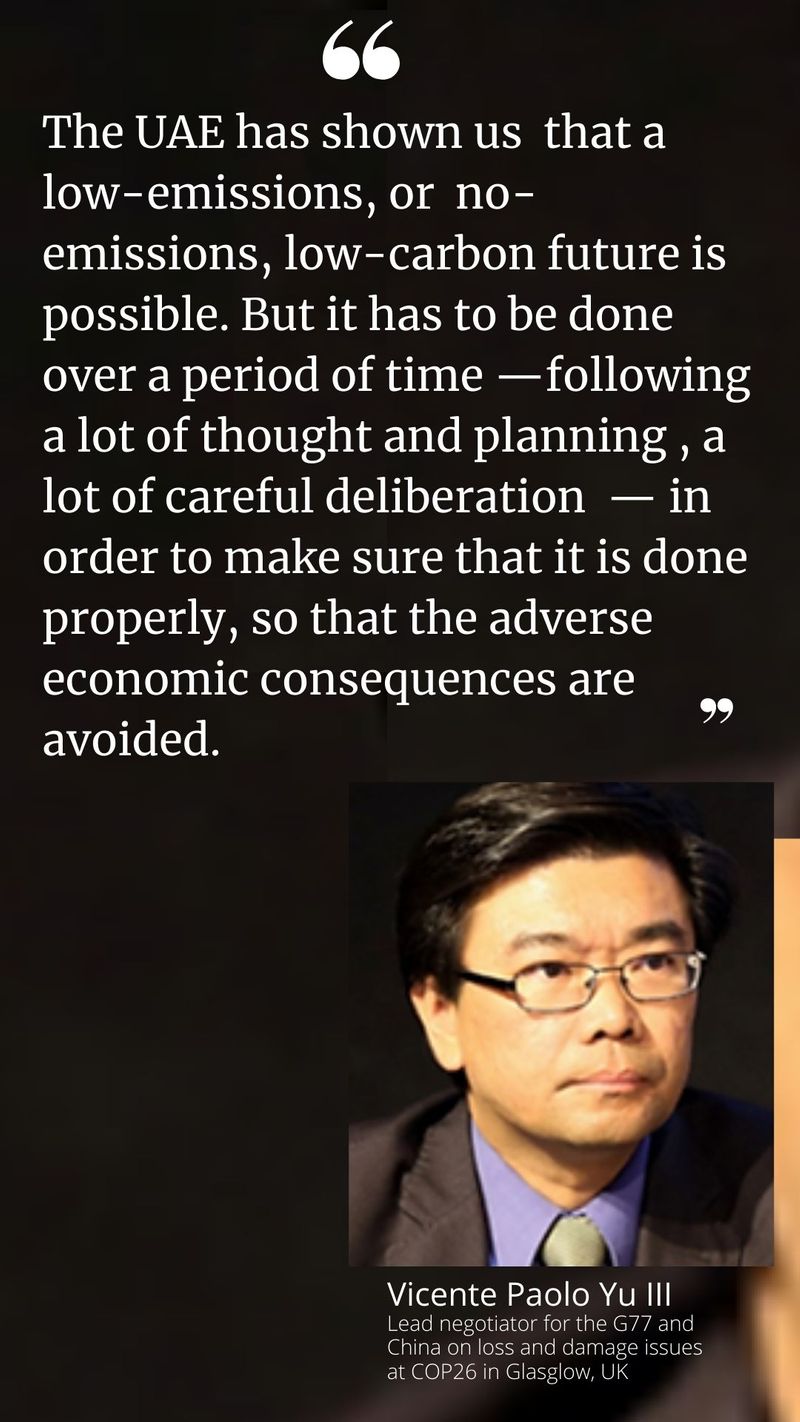

What India and China were putting forward in essence was that if you do not nuance that language, what it could actually do is to commit developing countries into having to transition before being ready for it. For example, in most developing countries, their current energy infrastructure, are still dependent on coal and oil. The energy transition needs to be carefully planned for and implemented.

So what I think India and China were explaining was: you have to look at the context of developing countries. Given that for many in developing countries, the need to provide energy and access to our poor population is very much important…and the introduction of, say, renewable energy technologies into our economies are still not at a sufficient scale to actually replace coal or oil right away, providing language that recognises the need for developing countries to have some flexibility in how they undertake that transition is very important.

When you put in language that is black and white, then you’re not actually not understanding the circumstances in the developing countries (which are different from the developed economies). One might end up trying to impose one-size-fits-all approaches or solutions that could work in developed countries, where energy infrastructure is sufficient, where renewable energy is becoming a bigger part of the mix, and they have the money and the technology to be able to do that. Many developing countries still don’t have that, so one might need to have differentiated approaches for developing countries so they can find solutions that are best for their conditions and priorities.”

With climate change, what are the urgent tasks?

We need to think about more sustainable communities, that would allow people to have decent and dignified livelihoods at home, that won’t force people to migrate.

- 1. If you think only about technology as the solution, such as electric vehicles for example that rely on batteries requiring rare earth minerals, such solutions could be expensive and beyond the reach of developing countries. Having that kind of approach, then you might have a resource grab, which may lead to political tensions. Perhaps a better approach is to have a more holistic perspective that fits technology solutions into the context of equitable and just transitions in the energy, economic, transportation, industrial, agricultural, and other sectors that prioritizes the generation of decently paid jobs, increased standards of living for the poor, while reducing resource use.

- 2. We should also think about how the high-consumption, high energy-use, high materials-use lifestyle in developed countries could be made more efficient so that these countries’ ecological footprint becomes lighter.

- 3. We should also think about how low-income, low-tech, low-livelihood patterns in developing countries are improved so they could have more income, in a way that would not repeat the mistakes of the developed world.

International climate negotiations is a big part of how we, as a global community, fight climate change. But it’s not the whole story. What’s more important is what governments do at the national level… how they engage with their people in serious conversations about their national policies that are needed to move their economies and societies towards an equitable and just transition leading to a more sustainable pathway.

What we need is a more equitable world, a “whole new world”.