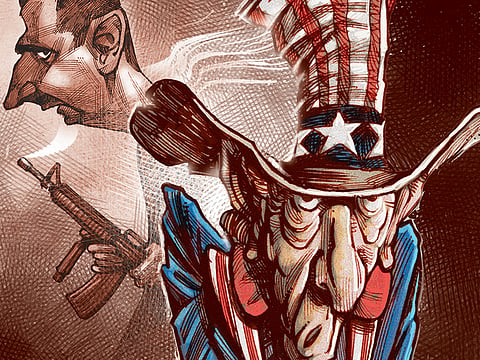

Will Al Assad stay or leave?

Beyond the regime in Damascus, it is clear that the main driver of US policy is Washington’s desire to contain the self-proclaimed Islamic State

On August 28, the United States State Department issued a statement on Syria. It said: “The United States remains strongly committed to achieving a genuine, negotiated political transition away from Bashar Al Assad that brings an end to the violence.”

It came right in the middle of intense speculation over a possible deal in the making, triggered by the latest swirl of diplomacy. Most intriguing has been a secret meeting between Saudi and Syrian officials, as well as a trilateral meeting in Doha that brought together the Russian, American and Saudi foreign ministers, and a visit by the Syrian foreign minister to Oman.

Some have been tempted to take such talk at face value.

‘Washington confirms its determination to overthrow Al Assad,’ declared the headline of a piece in the Syrian Press Centre, a popular opposition website, on the day the US State Department issued its statement.

Throughout the Syrian conflict, American, British and French statements on Syria have shared a common characteristic: They create impressions, some subtle and others explicit, that the fall of Al Assad is inevitable and just around the corner; and that they are committed to achieving it.

Recall the ‘Friends of Syria’ brand, created quite early on in the Syrian uprising. In February 2012, France announced it was planning to set up the ‘contact’ group on Syria after Moscow and Beijing vetoed a United Nations Security Council resolution against Al Assad.

“France is not giving up,” Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy had said back then. It lasted quite a while and produced some memorable statements. Take this declaration by the spokesman for the French Foreign Ministry after the third Friends of Syria conference, which was held in Paris in July 2012, as an example. “This meeting has seen record participation, with more people than the previous two meetings. It shows the mounting pressure against the bloody Al Assad clan in Syria.”

The idea that “record participation” in a meeting in Paris meant that pressure on Al Assad was rising is easy to dismiss now, with the benefit of hindsight. But such statements, articulated at international conferences, exerted a powerful and lasting influence on hopes, fears, and calculations of the different parties to the war.

These days, scepticism is a more common reaction to such talk. ‘Even if Russia Abandons Al Assad, the US will not,’ went a headline in Zaman Al Wasl, another popular opposition website.

On the ground, a lot has changed since the earlier days of Friends of Syria. It has become clear now that Al Assad has lost almost any realistic hope of regaining control of all Syria and the only remaining question is how long he can hold on to a number of core areas, namely Damascus, Homs and the coast. Even these are increasingly under attack.

So if the Americans’ analysis of the situation on the ground leads them to believe that Al Assad is on his way out, their diplomatic push would likely be aimed at managing the transition.

If, on the other hand, they see him as staying, it would more likely focus on delineating zones of influence, in dialogue with Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

Beyond Al Assad, it is clear that the main driver of US policy is Washington’s desire to contain the self-proclaimed Islamic State and the aim of American diplomacy seems to be focusing other powers on that priority.

The Russians appear to be quite happy with that policy and they have been trying to convince the Saudis to forget their problems with Al Assad and focus on the self-proclaimed Islamic State. The Iranians are already on board, providing the missing ground force for the American effort in Iraq. The Turks seem to have jumped on board, although the terms of their agreement with the Americans remain mired in mystery and their Kurdish ‘problem’ appears to be at the forefront of their entry into the war.

America’s diplomacy is helped by the fact that all the warring powers are, to varying degrees and in different ways, under threat from the self-proclaimed Islamic State, and therefore likely to take kindly to America’s priorities.

The most awkward position is that of Syrian rebel factions. To apply for the status of America’s ground troops in the war, they must focus on the self-proclaimed Islamic State and perhaps forget about fighting the regime completely.

So back to that statement by the US State Department; both extreme scepticism and unquestioning repetition obscure the fact that for the Americans, Al Assad remains a detail and his place in the puzzle depends mostly on his utility or lack thereof, in their fight against the self-proclaimed Islamic State.

Rami Ruhayem is a BBC Arabic correspondent.