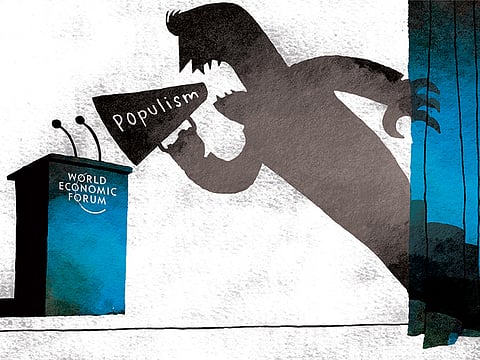

Shadow of populism hangs over Davos

Corridor conversations turned to the US presidential election and refugees

There are certain words used at Davos that get people nodding in agreement. These include “sustainability”. There are others that are guaranteed to get the crowd at the World Economic Forum looking concerned. This year’s word was “populist”.

The populists are those political forces that advance ideas that are generally seen as dangerous or facile to those at Davos. These ideas include the US building a wall to keep out immigrants, Britain leaving the EU or anybody raising tariffs or dismissing climate change. And these forces are on the rise.

The shadow of Donald Trump loomed over Davos this year. So did the prospect that refugee flows into Europe will undermine centrist leaders such as Angela Merkel, the German chancellor. More broadly, those at Davos were aware that they increasingly represent the “unpopular” — the business and political elites that are the targets of public anger and disillusionment.

Sooner or later, most corridor conversations in Davos turned to the US presidential election. It was gradually dawning on people in the Swiss resort that either Trump or Ted Cruz, the Texas senator, would probably win the Republican nomination, and that the “unthinkable” — a Trump or Cruz victory in November’s presidential election — could happen.

Not everybody accepts this analysis, of course. Eric Cantor, the Republican former majority leader in the House of Representatives, told a session at Davos that he doubted that Trump’s candidacy would survive the primary elections that decide the Republican nominee. But then again, Cantor lost his own supposedly safe seat in 2014 to the populist insurgent Dave Brat — which hardly suggests an infallible grasp of public sentiment.

European politicians, meanwhile, are battling their own populists. Merkel, who normally gives a warmly applauded speech at Davos, had to stay at home this year to deal with the refugee crisis. In her absence, Joachim Gauck, Germany’s president, took to the stage to issue a thinly veiled attack on Merkel’s refusal to put a numerical limit on the number of refugees Germany can accept. He argued that “if democrats do not want to talk about limitations then populists and xenophobes will”.

Gauck was not alone in his warnings about the political effects of refugee flows. Mark Rutte, the Dutch prime minister, warned that Europe has “six to eight weeks” to stem the flow of migrants, before the pressure to reimpose frontier controls within the EU becomes irresistible.

Meanwhile, Davos also grappled with the idea that the UK might actually vote to leave the EU this year.

Sources of discontent

David Cameron, the UK prime minister, last Thursday gave a confident speech in Davos, where most people are inclined to believe that Britain will ultimately vote to stay in the EU. But that confident stance involves dismissing recent opinion polls that suggest a British exit is quite likely.

Amid all the warnings about populism, the Davos crowd were making earnest efforts to engage with the sources of discontent. All European political leaders now talk of the need to control flows of refugees. The trouble is that their proposed long-term solutions — peace in the Middle East, a Marshall Plan for north Africa — sound unconvincing. As the plight of the refugees from Syria and elsewhere worsens, public concern in Europe mounts.

As ever, Davos featured much earnest discussion of the problem of inequality and calls for more displays of corporate social responsibility. But even technological progress, which is normally regarded as an unalloyed good in Davos, is now arousing concern. There has been much debate of the fear that robots will displace low-skilled workers, leading to rises in unemployment and poverty.

Yet Davos 2016 has also provided some evidence that the populists are not having things all their own way. Two recent election winners who have aroused particular interest are Mauricio Macri, the Argentine president, and Justin Trudeau, the prime minister of Canada.

Both men speak fluent Davos. Macri, the first Argentine president to appear at Davos in more than a decade, promised to regain the confidence of foreign investors, cut bureaucracy, crack down on corruption and invest in infrastructure. Trudeau is a standard-bearer for causes that are heavily promoted at the WEF — including feminism and action on climate change.

The Davos mood on populism was more one of deep concern and uncertainty than full-blown panic. But the next 12 months will present a series of crucial tests.

It is possible — if still unlikely — that when the WEF gathers this time next year, Trump will be US president, the UK will have voted to leave the EU and border controls will have been restored across Europe. Those developments would turn the Davos world upside down.

— Financial Times