Yemen’s federal solution needs buy-in

Al Houthis and southerners have reservations over details of federal solution currently on offer

Yemen needs a new federal constitution, acknowledging that its diverse people cannot be successfully governed as one unitary state run from the centre by an all-powerful presidency. The challenge in any peace talks after the current conflict will be to both define the borders of the regions and also define how much autonomy the regions should have.

This discussion is exacerbated by a deep mistrust of any state institutions after the decades of poor central governance under former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who was particularly disinterested in promoting good governance and operated on divide-and-rule principles, resulting in a gradual breakdown of state institutions and the disintegration into chaos.

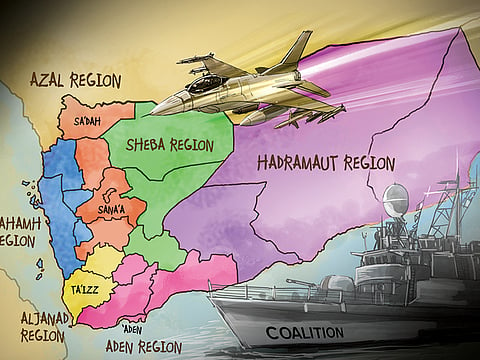

The 2014 National Dialogue proposed the creation of six major regions to cover the 21 governorates that currently are the main units of sub-national government. Despite the National Dialogue being well attended and surprisingly hopeful, the regions did not win universal support. Al Houthi leader Mohammad Al Bakhiti rejected the proposal “because it divides Yemen into poor and wealthy regions” and a southern delegate, Mohammad Ali Ahmad, said that “what has been announced about the six regions is a coup against what had been agreed at the [NDC] dialogue”.

Even so, the Dialogue was well attended and included a wide range of opinions, which backed its conclusions. Its guiding committee included President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi, Abdul Kareem Al Eryani of the General People’s Congress of Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yassen Saeed No’man from the Yemeni Socialists, Sultan Al Atwani of the Nasserite Unionist Party, Yassin Makkawi of the Peaceful Southern Movement, Saleh Bin Habra from Al Houthis, and Abdul Wahab Al Ansi of the Islah Party.

The Dialogue’s proposal was that former North Yemen would get four regions, including one central region Azal, which unfortunately would include both Al Houthi heartland around the far northern city of Saada and also stretch down the top of the Yemeni mountain chain to include capital Sana’a.

Al Houthis argued that “their” region should not only be separate from the capital, but it should also include a port so that they can develop their economy more effectively. The rejection of this demand by Hadi was one reason behind Al Houthis’ march south to capture Sana’a and much of the rest of Yemen, leading to the current Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) intervention under Operation Restoring Hope.

The former South Yemen would get two regions. One based on the former capital Aden, Yemen’s largest port, and would include Lahej and Abyan. The other is the massive territory of Hadramaut, stretching all the way to Oman.

Inevitable disputes

Any peace talks will need to confirm these regions and also define their areas of competence and the authority of the regional governors. As when launching any federal system, there will be inevitable disputes between regions and the federal government. Federal states like the US and Germany have constitutional courts to manage this process, but the Yemenis will have to rely on their ability to negotiate across clan and sect. And the bizarre alliance between Al Houthis and their former persecutor Saleh proves that compromises can be made.

From early 2000s, the then-president Saleh waged war on Al Houthis “with such brutality and incompetence that Al Houthi movement grew in size and fighting ability, gaining sympathy from northern tribes who suffered in the wars” according to Robert Worth, the author of The Houthi Enigma, writing in the New York Review of Books.

But after Hadi’s government lost control of the country in 2011, “with Al Qaida bombers and kidnappers running rampant, Al Houthis were the only group with the cohesion and discipline to hold terrain. They grew even stronger after forming a tactical alliance with their former enemy, ex-president Saleh, who still controlled much of the military”, said Worth.

If Al Houthis and Saleh can fight and work together, so can anyone else. The key is to have aims that everyone shares, which is difficult in a country as young as Yemen, which was only united for the first time ever in 1990. Such unity of purpose will require buy-in from northern tribes like Al Houthis and Al Ahmar; the coastal tribes of the Tihama; the southerners around Aden who, are divided between rejectionists and those willing to try and make a united Yemen work; and the remote people of the valleys and deserts of the huge eastern territory of the Hadramaut, who are troubled by Al Qaida fighters seeking space for themselves (who are totally excluded from any talks).

The coalition and the GCC are fighting for such a dialogue. Five of the GCC member states have sent troops to seek to restore the direction created by the National Dialogue and to restrain Al Houthis and their allies.

It may well be that future peace talks treat the Dialogue’s proposals as a starting point and there is an expectation that Yemen’s Vice-President Khalid Bahah will run the national dialogue after receiving full powers from the president, including a complete review of the constitution drafted by the National Dialogue.