Why India’s new Chief Justice brings hope

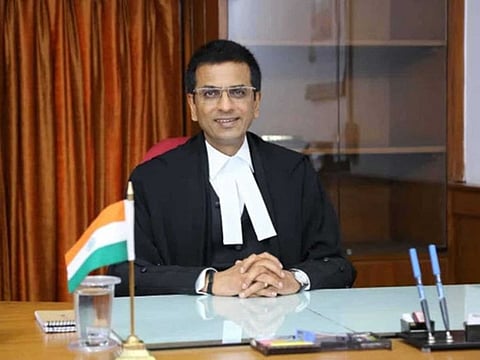

Justice D Y Chandrachud is a man on a mission who restores dwindling optimism

No Chief Justice of late has ascended with as heavy a weight of expectation as India’s new top judge D Y Chandrachud.

In some of his first words after the swearing-in as the country’s 50th Chief Justice he took off from where he had paused calling out the structure of the legal profession ‘feudal, patriarchal and not accommodating of women,’ an ‘old boys club’ whose walls need to be taken down for an inclusive judiciary that does justice to both women and the marginalised.

The Chief Justice has set liberal precedents, his resume includes judgements like striking down section 377 that criminalised homosexuality by calling it an ‘anachronistic colonial law,’ supporting the right of women and girls between 10 to 50 to enter Kerala’s Sabarimala temple terming its ban unconstitutional and right to privacy, where he overruled his own father’s judgement during Indira Gandhi’s emergency by calling it ‘seriously flawed’ and emphasising personal liberty as paramount.

Many would label him more a crusader than a judge and his stance on women stands like a bulwark when their respect has taken a beating with convicted rapists being freed, normalised.

In a historic judgement he demolished decades old discrimination by bringing unmarried women on par with their married counterparts by giving them the right to abortion and access at 24 weeks, correcting inequality in reproductive rights.

That there are plenty of regressive laws in the pool was highlighted again when as part of a two- judge bench he directed centre and state governments to remove the invasive two- finger test on rape victims from medical curriculum.

But India is a country where course correction is resisted as vigorously as timely justice. It enables power to be ceded and making those who have lazily lived under the patriarchal spotlight, insecure. It is everything the new Chief Justice looks to dismantle by walking the talk on ‘feminist thinking,’ predictably he was accused of spreading ‘toxic feminism.’

Defence against oppressive structures

There is more. ‘The rule of law, if understood and implemented properly, is a defence against oppressive structures such as patriarchy, casteism, and ableism,’ the Chief Justice’s remarks were enough to bring the twisted cancel culture brigade swarming to social media with the hashtag #NotMyCJI. Hopefully with Chief Justice Chandrachud, they won’t get much time to rest.

It is not just his judgements that have stood out, Chief Justice Chandrachud has also been unafraid to walk the road alone, his dissenting voice on occasion more powerful than a majority judgement. He was outnumbered 4:1 in the Aadhaar case where he called the move to link bank accounts with Aadhaar a ‘violation of fundamental rights’ and ‘the assumption that every individual who opens a bank account is a potential terrorist or a launderer is “draconian.”

Minority opinion or not, his views on dissent are clear. He rightfully terms it the ‘safety valve’ of a democracy, ‘The blanket labelling of dissent as antinational or anti-democratic strikes at the heart of our commitment to protect constitutional values,’ a memo to go by when activism is silenced in jail.

Perhaps Law Minister Kiren Rijiju has more than noticed, making his displeasure at the government’s inability to appoint and transfer judges, public.

Centre can only question the recommendations of the five- judge collegium but cannot derail any posting. The CJI will be aware that the executive is breathing down at a time when judicial overreach has tarnished the reputation of courts.

The backlog of cases and slow wheels of justice remain our judiciary’s collective blot. Millions of cases are pending in the country as people age but don’t see an outcome. Divorce cases linger on for decades, property disputes are resolved after a petitioner passes away.

Away from the high profile judgements, this is the reality of Indian courts, a reputation that isn’t exaggerated. Compounding matters is vacancies, currently 5000 seats in the lower courts need to be filled urgently. Reforms need a parallel but consistent outing to restore common man’s belief in the system.

With great power comes great responsibility, that proverb has been turned on its head but there are still a few good men.

From introducing online streaming of court proceedings to the label of being a feminist CJI, a badge he seems to wear proudly or the endearing family photo with his daughters who have special needs, Chief Justice Chandrachud is a man on a mission who restores dwindling optimism. But in his own words, it is not just about saying but also about doing.

He has two years to leave that legacy.