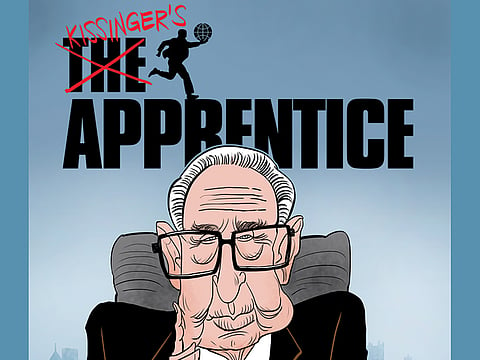

What did Henry Kissinger Tell Donald Trump?

Pragmatism, which the former US secretary of state undoubtedly counselled America’s President-elect, must prevail

A few days ago, American President-elect Donald Trump met the former United States secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, to discuss “events and issues around the world”. This was the second encounter between the two men in recent months, after a controversial mid-May 2016 gathering at Kissinger’s home when the billionaire businessman sought support from members of the Republican establishment, ostensibly to shore up his poor foreign policy credentials.

To be sure, Trump eschewed Republican foreign policy orthodoxy throughout the campaign — rejecting the 2003 War for Iraq, calling into question America’s military alliances, dismissing the benefits of international trade and planning to call for a temporary ban on Muslims to enter the US (which Kissinger urged him to abandon) — going so far as to declare, at least then, that he would be more comfortable with another nominee. According to a press statement issued by Trump last Thursday, the “President-elect and Dr Kissinger discussed China, Russia, Iran the EU and other events”, which was to be expected though few know what the strategist told the novice leader.

Kissinger spoke about his meeting on CNN this past Sunday, opining that “Not enough attention was paid to the fact that [Globalisation] was bound to have winners and losers, and that the losers were bound to try to express themselves in some kind of political reaction”. Flattering the president-elect, Kissinger orated that Trump was “the most unique [winner] that I have experienced in one respect”, adding that the man had “No baggage”.

Globalisation is an important topic of course, but it is significantly weakened, now that protectionism preoccupies everyone, everywhere. Yet, by focusing on it, Kissinger avoided comments on the three key concerns that the two men probably discussed in great detail — with the 93-year old strategist coaching, yes coaching, his newest apprentice.

Given Trump’s penchant to work with Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Kissinger caution vis-a-vis Russia was probably topic number one. Competition between the two countries, which struggled during the Cold War to delegitimise each other, reached dangerous levels in recent years as Moscow abolished the Warsaw Treaty Pact, but western powers retained the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato). Putin is still livid about this and does not plan to forgive Washington for pushing Nato closer to Russia. He vociferously objects to any and all western involvement in his backyards, including Ukraine, most of the countries in what was the former East European arena, the Caucasus and elsewhere.

For his part, Trump repeatedly criticised Nato countries and plans to send everyone a bill, oblivious to treaty obligations that are followed to the letter. Irrespective of any changing long-term perspectives in Europe, Kissinger most probably cautioned Trump to be wary of Putin, whose strategic skills are far superior to anything the New York billionaire can field. Kissinger knows that the Russian is anxious to restore his empire and prevent a third break-up after the 1917 and 1991 revolutions, even if how modern-Russia confronts serious economic challenges will determine its fate. What Trump can do about these Russian problems is peripheral, though he can lower tensions between Washington and Moscow.

The second grave topic is China and, in the words of the Chinese President Xi Jinping, US-Chinese ties are now at a “hinge moment”, something that does not bode well as Trump is likely to walk away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) “from day one”. Trump declared that he planned to issue a note of intent to withdraw from the TPP trade deal on January 20, 2017, calling it “a potential disaster for our country”. Instead, he said he would “negotiate fair bilateral trade deals that bring jobs and industry back”. Of course, TPP would be “meaningless” without US participation and, if Trump goes through with his ideas, chances are great that fresh tensions would be added to the mix.

Kissinger, the father of the US-Chinese rapprochement that allowed former US president Richard Nixon to go to Beijing in 1972 and who masterfully used China against the then USSR, probably cautioned Trump not to surrender this critical card. In fact, every head-of-state, including the largely negligent administration of US President Barack Obama, opted for close cooperation with China on key issues such as North Korea’s nuclear development and climate change, even if Washington’s putative “pivot to Asia” was meant to check Beijing’s expansion.

Trump cast China as a foe throughout the campaign, threatened to impose new tariffs, and declared that the country was a currency manipulator. Irrespective of such bombastic declarations, the two sides will now work together to focus on cooperation, manage differences and usher in mutually beneficial policies, something that financial necessities will impose on both. Pragmatism, which Kissinger undoubtedly counselled Trump, must prevail and few should be surprised if and when the president-elect decides to work closely with Xi.

The most critical area that most likely preoccupied Kissinger and Trump was the Middle East, as the two men prepared to further strengthen Israel and, commensurately, weaken Arab states. The nonagenarian devoted most of his adult life to ensure the integration of Israel in the area and most likely reminded his host that the wars in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and elsewhere were/are all meant to guarantee the inclusion of minority regimes in the area as “natural entities”. The concern over Iran was most likely touched upon too with Trump confronting challenges from his ultra-conservative advisors — and potential secretaries of defence and national security counsel personnel — versus Kissinger who always opted for “divide-and-rule” tactics.

Time will tell whether Trump listened to Kissinger, but chances are great that the apprentice displayed awe in the presence of a strategist whose undeniable expertise for gloom and doom remain unparalleled.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of the just-published From Alliance to Union: Challenges Facing Gulf Cooperation Council States in the Twenty-First Century (Sussex: 2016).