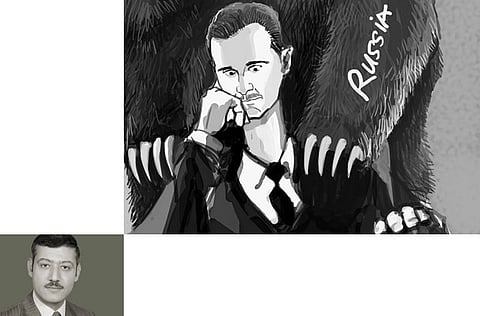

Russia using Syria to assert dominance

Putin using crisis as a tool to demonstrate that it remains a key world power

Since the beginning of the Syrian uprising more than 17 months ago, Russia has become the focus of diplomatic and political efforts to end the crisis. By establishing itself as the key patron of the Damascus regime, Moscow has in fact succeeded in occupying centre stage in the Syrian question.

Many took the Russian position lightly at the beginning, believing that the mercantilist attitude of post-Soviet Russia would eventually lead it to selling out the Syrian regime when the right offer was made. That argument proved to be inaccurate, at least until now. Russia has resisted all attempts to abandon its ally despite the tremendous pressure exerted by the West and the Arab League. For many, Russia’s position was perplexing, leading to speculation as to the true motives behind it.

Most analysts argue that Moscow’s policy on the Syrian crisis derives mainly from commercial and logistic interests, i.e. Russia wishes to profit from selling arms to the Syrian regime and seeks to maintain its naval facility at the Syrian port of Tartus. This argument is flawed. Russia can still sell arms to Damascus even in the eventuality of a regime change.

A country which has been dependent on Russian weapons and military technology for more than six decades cannot simply decide to switch to another producer. In addition, the training and the combat doctrine of the Syrian army is Russian and will remain so for the foreseeable future even if a new regime comes to power in Damascus. The shift in the political orientations of the new regime will not change this fact for at least a decade.

Ten years after the US occupation, Iraq remains a major buyer of Russian military equipment. The US government has recently signed a multi-billion dollar contract with the Russian arms industries to supply the Afghan army with tanks, armoured vehicles and other military hardware.

Trust deficit

Washington still does not have enough trust that the pro-US ruling elite in Baghdad and Kabul will not turn against it or be replaced by more antagonistic regimes. There is also the eventuality that US-made arms might fall into the hands of anti-US elements, one reason that Washington has been so far reluctant to supply the Syrian opposition with US-made military equipment.

Finally, even under the current conditions, Syria is by no means a major buyer of Russian arms — accounting for just 5 per cent of Russia’s global arms sales in 2011. To put it plainly, arms sales to Syria do not have any significance for Russia from either a commercial or a military-technological standpoint and Moscow does not have much to lose from this perspective should the Syrian regime collapse.

The Russian Navy’s logistical support facility at Tartus is similarly unimportant. It essentially amounts to two floating moorings and a few buildings. From a military viewpoint, Tartus has more symbolic than practical significance.

Russia’s position on the Syrian crisis can better be explained in two contexts: domestic and external. Domestically, Russian President Vladimir Putin seems to be convinced that any popular protest in any part of the world, and especially in the Middle East, is supported by the US; it will have a domino effect and it will hence be inspiring for his fast-growing internal opposition. Therefore, when Putin stands against change in Syria, he is in fact defending himself not the Syrian regime.

Externally, Russia believes that it has been taken lightly by the West on several world issues. On Libya, for example, Moscow thinks that it has been fooled by the US when it was persuaded to support a UN Security Council resolution to protect civilians from the wrath of former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, but that was used to bring about regime change in Tripoli.

Out of deep bitterness, Russia’s position on Syria is meant to punish the West for not showing enough respect, but it is also using Syria as a tool to demonstrate that it remains a key world power and that its interests must be taken seriously.

Finally, Russia seems to be concerned about the rise of political Islam in its surroundings and the role played by Turkey to foster Islamic trends in the Middle East, the Balkan, Central Asia and Caucasia. As a third of its population are Muslim, Russia is absolutely alarmed by the rise of Turkey and its interpretation of Islam.

Should the Syrian regime fall, Turkey, which is seen by Moscow as a major regional rival, is set to benefit most. By supporting the Syrian regime, Moscow is hence attempting to prevent a fundamental change in the balance of power.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is the Dean of the Faculty of International Relations and Diplomacy at the University of Kalamoon.