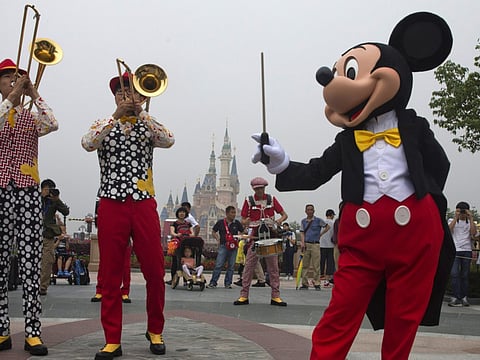

How Mickey Mouse works his magic in China

Watching the pleasure and joy in their faces, girls in their princess costumes, convinced me that some of Walt’s values — American values — were leaking through

The crush at the entrance to Shanghai Disneyland was particularly chaotic, even for China. Squeezed and jostled, I cursed under my breath.

It didn’t seem like this was going to be the happiest place on earth if everyone kept trying to cut in line.

But once inside the park, the crowds changed behaviour. They were polite. Everyone waited patiently in long lines, respectfully observing rules like no spitting or allowing children to use bushes as toilets. They behaved like loyal Disney fans everywhere. As I reflected on my memories, my excitement both as child and as parent, I wondered what the Chinese, adults and children, were feeling and thinking. I pondered the larger questions of how culture and values are transmitted and internalised. How does indoctrination work?

Shanghai Disneyland, the first Disney theme park in mainland China, opened in 2016 after five years of construction. Located in Pudong, Shanghai, the park is operated by Walt Disney Parks, Experiences and Consumer Products and Shanghai Shendi Group, through a joint venture between The Walt Disney Company and Shendi. The park has a visitor attendance of 5.5 million guests. The park has seven themed areas: Mickey Avenue, Gardens of Imagination, Fantasyland, Treasure Cove, Adventure Isle, Tomorrowland, and Toy Story Land.

I visited the 963-acre park last year. And I had my family on my mind the whole time. Watching Chinese families frolic in Walt’s magic kingdom drew me back to the first time my parents took me to Disneyland in Anaheim — and the first time I introduced Disney to my own children. For my parents, Chinese immigrants to the United States, bringing the family to Disneyland was a partial fulfilment of the American dream. When I began photographing in China in the early 1980s, Chinese people seemed wary of anything cultural. Most Chinese distrusted the Communist Party’s sanctioned art; it was not entertainment, it was propaganda. They knew it was all fake, but had little opportunity to express their own individual experiences. The government’s ham-fisted attempts at culture pushed toward foreign influences, especially American.

Like America in the 1950s, China is now undergoing a middle-class boom with similar aspirations; material wealth, leisure, travel, sophistication. For American baby boomers, visiting Disneyland became a necessary rite of passage. Globalisation has helped make institutions such as Disney popular in China. Will going to Disneyland now become a ritual for aspirational Chinese families?

When the park was still in the planning stages, the Chinese government insisted Shanghai Disneyland needed to be different from the other magic kingdoms, especially the parks in Asia, which are copies of their American counterparts. Iconic figures and structures, like Mickey and the Enchanted Castle, are of course featured. But Main Street — too western — was replaced by Mickey Avenue, a mash-up of western and eastern architecture. The castle, the largest of the six Disney castles, accommodates all the princesses in the Disney universe — perhaps because only one princess would be too elitist for Communists. And although there are long lines for giant turkey legs, Chinese food remains the most popular fare. The result, as Disney’s CEO, Bob Iger, claims, is a park that is “authentically Disney, distinctly Chinese.”

I asked several Chinese park-goers what their Disney experience was like. Were they assimilating western values or simply having a good time? Older teenagers and adults claimed immunity to any ideology. But I am not so sure the youngest children were unaffected. Watching the pleasure and joy in their faces, girls in their princess costumes, convinced me that some of Walt’s values — American values — were leaking through.

— New York Times News Service