Godse, Gandhi, and India’s binary problem

In TV shouting matches and debates, the killer casts a shadow as much as the killed

Last week, as the parliamentary elections in India got over, one man who died long ago, rose — again — from the ashes and dominated the discourse: Nathuram Godse.

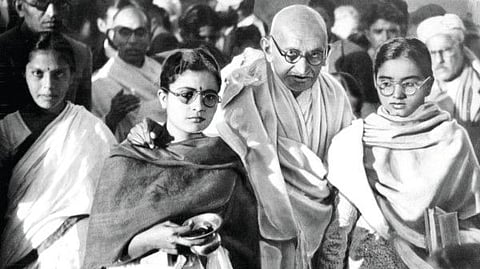

Godse shot dead the greatest Indian leader of modern times, Mahatma Gandhi, at a prayer meeting in Delhi, on January 30, 1948, less than six months since India’s independence from the British rule on August 15, 1947. Seventy-one years later, Godse still walks the length and breadth of India, with the Mahatma in tow, two ghosts chained inseparably to each other by history.

Five years from now, when it is time for the next general elections, Godse, as is his wont, will take centre-stage.C.P. Surendran

In TV shouting matches, in speeches, in protest rallies, and debates on India’s future, the killer casts a shadow as much as the killed. Why? On May 23, the elections results will be declared.

But five years from now, when it is time for the next general elections, Godse, as is his wont, will take centre-stage. The reason for this is that Godse, while arguing for Hindu consolidation across all castes, believed in a Hindu Rashtra (state), and differed from the secular nation that the Indian constitution envisaged. That question has not been fully answered. The right is not equipped to raise the issue of the rights of the majority and the left is not quite sure how to define those rights without running the risk of adopting double standards. Which is why Godse can’t be exorcised from the body politic.

Last fortnight, actor Kamal Haasan in an election speech said Godse was India’s “first Hindu terrorist”. Ironically, in 2000, Haasan had made a movie, Hey Ram, which spins around an aggrieved Hindu fundamentalist’s plot to kill Mahatma Gandhi. Haasan’s speech piqued a BJP candidate and a Hindutva leader, Pragya Singh Thakur, an accused awaiting trial in the 2006 Malegaon bombings in Maharashtra which killed 37 people. She said, “Godse is a patriot.”

Indian media predictably went into hysterics. The ruling BJP prime minister, Narendra Modi, said he found Pragya Thakur’s words “unforgivable”. That brought the curtains down on the controversy — for the moment.

But Godse will not go. He is the eternally revenge seeking Ashwathhama (son of Drona, the guru, and commander of the villainous Kaurava family in the Mahabharatha; Drona was tricked and killed by the good Pandavas) of the modern times. India’s political, social, and media values are polarised largely along the lines of Godse and Gandhiji. The binary politics this implies simplifies the many layered Indian reality.

It will be difficult for anyone objective who has read the long court statement that Godse made first before special judge Atma Charan’s court in the Red Fort, Delhi (on November 8, 1948), and again before the Punjab High Court where Godse went in for appeal (on May 2, 1949), before a bench of three judges chaired by justice G.D. Khosla.

Justice Atma Charan had sentenced Godse and his friend, Narayan Apte, to death by hanging on murder charges. When they went in for appeal before Justice Khosla, Godse did not plead for a lesser sentence but he argued against conspiracy charges implicating seven others including Apte. He said the assassination of the Mahatma was solely his responsibility. He and Apte were hanged on March 15, 1949 and their ashes submerged in the Ghaggar river in Ambala, Punjab, rather hastily by the police for obvious reasons.

The matrix of the murder evolved to become more than the act itself because of Godse’s allegiance to Hindutva outfits like the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayam Sevak Sangh (RSS). The Mahasabha is a right wing Hindu nationalist organisation formed in 1909 in reaction to the genesis of All India Muslim League in 1906, and the subsequent British decision to create a separate Muslim electorate under the Morley-Minto Reforms (1909). The RSS is a paramilitary Hindutva organisation set up in 1925. It is typical of the Indian chattering classes that Lala Lajpat Rai — a great, early leader of the Independence movement — actually was one of the founders of the Mahasabha. An admittance of this fact would naturally complicate the contemporary liberal discourse.

The truth that emerges from Godse’s hearings is that neither outfits had any formal role in his decision to kill the Mahatma, yet the two continue to be seen as guilty by adjacency. Indeed, one of the accused Veer Savarkar, a Hindu Mahasabha leader, was exonerated by the trial judge on all counts. But he continues to be associated with the murder of the Mahatma in the lazy binary conflation of issues that has come to characterise the contemporary Indian discourse.

The actual resolve to end the life of the Mahatma crystallised, according to court hearings, around January 13, 1948, when Gandhiji went on a fast for life to force the nascent Indian government of Pandit Nehru to pay the newly formed Pakistan reparation charges amounting to Rs550 million. Within three days of the fast the government buckled, and Godse concluded Gandhiji’s ‘minority appeasement’ would result in the utter defeat of Hindu interests.

In his memoir, The Murder of the Mahatma, Justice Khosla describes the effect Godse’s statement: “The audience was visibly and audibly moved. There was a deep silence when he ceased speaking. Many women were in tears and men were coughing and searching for their handkerchiefs... I have... no doubt that had the audience of that day been constituted into a jury and entrusted with the task of deciding Godse’s appeal, they would have brought in a verdict of ‘not guilty’ by an overwhelming majority.”

This admission does not make Godse the saviour of secular India though it explains a certain extenuation of his motives; it was murder. The fact is that a martyr and a terrorist are not mutually exclusive terms. Indeed, very often they could be the same, depending which end of the telescope you are looking into. If India gets out of its rather facile binary value judgement process, it will begin to make more sense for itself. There’s something about Godse. The Mahatma, too. Now, let’s talk.

C.P. Surendran is a senior journalist based in India