France intervention in the Central African Republic

The country is using military intervention in Africa for humanitarian means but also to boost its leader’s polls

Escalating French military involvement in the Central African Republic represents the latest application of what might be termed the Hollande doctrine, a self-consciously benign form of armed interventionism based on international authority and local consent. In sum, France’s President Francois Hollande has developed a new formula for invading other people’s countries, by doing it nicely.

Since taking office in May last year, Hollande has ordered, or perpetuated, French military operations in Ivory Coast, Somalia, Mali and now the CAR. He was also a keen backer of western military intervention in Syria. These engagements were preceded by the Anglo-French intervention in Libya in 2011, under Hollande’s predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy.

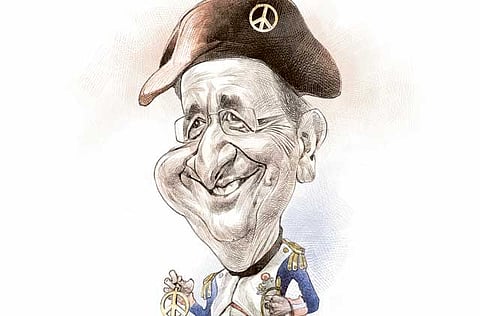

For France’s happy interventionists, each expedition has had a primary humanitarian focus. But they have also served to bolster fading French international prestige, especially in its former African colonies, and to boost Hollande’s low approval ratings. Oppressed by economic woes, the French appear to enjoy incisive military action abroad (as long at it works). As Napoleon, another pint-sized French leader knew, la gloire (glory)makes little men feel grand.

The Hollande doctrine promotes a broader agenda, about how to “do” international security. It is a reply to the perceived US retreat from historical responsibilities in Europe, the Middle East and elsewhere. It is about the advance of China in Africa, wielding power but scant responsibility. It is about showing European leadership (the contrast with perceived British apathy is marked and savoured).

As much as anything, the doctrine is about stemming the tide of Islamist extremism and sectarianism that threatens swathes of territory from the Horn of Africa to the Sahel and Maghreb and potentially, the soft European underbelly of which France forms a vulnerable part.

But more than that, the new approach is Hollande’s answer to a more infamous justification of armed humanitarian intervention, promulgated by Tony Blair in Chicago in 1999, and known as the “Blair doctrine”. The then British PM was responding to the crisis in Kosovo that year, and later rehearsed his theories in Sierra Leone.

But the interventions in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003), which had less to do with humanitarianism and more to do with global power politics, ruined Blair’s case and in the eyes of many, his reputation. The “unilateralist” Iraq war was fiercely opposed by France. Hollande is now in the process of perfecting France’s antidote.

The Hollande doctrine, as applied in Africa at least, aims specifically to supply humanitarian security assistance in states where law and order has broken down. Secondly, it only operates with UN backing or acquiescence, and preferably the support of the African Union and, in West Africa, Ecowas.

Thirdly, it seeks the prior consent of local parties, namely those who most closely share western values and interests. In Ivory Coast, for example, this was the election winner, Alassane Ouattara, whose opponent, Laurent Gbagbo, refused to step down. Finally, the objectives of any intervention are defined and limited, with the aim of handing over to regional peacekeepers, as is happening slowly in Mali.

In the case of the CAR, Hollande has secured UN security council authorisation, the backing of the AU, the EU and the US, and an enthusiastic invitation from local factions loyal to the deposed president, Francois Bozize, which launched a new effort on Thursday to regain power. The additional French troop deployment will, in theory, be limited in scope and time.

This new approach promises considerable longer-term benefits for Hollande and France, assuming it does not go horribly wrong, which it certainly could. As Hollande has admitted, no such operation is without risk.

“[The CAR] has become the newest focus of an effort by Hollande to recast and revive his nation’s influence on a continent where its erstwhile clout has been challenged by the growing ascendancy of China,” said the New York Times. “Far from unilateral action the new approach draws on the twin notions of international approval and the rapid embrace of African forces to take over the kind of French deployment seen in Mali.”

Hollande’s doctrine has the additional advantage of avoiding past mistakes, when France forcibly intervened in Rwanda and elsewhere in favour of favoured leaders, or simply to maintain control (as in Algeria), with often disastrous results.

“This humanitarian security intervention is a far cry from the self-interested military meddling of the immediate post-colonial era,” said regional analyst Paul Melly. “Hollande has argued that the relationship between France and Africa must be a partnership of respect, even when there are disagreements. And he has gone out of his way to consult African leaders before launching military action.”

Hollande, following a re-evaluation set in motion by former prime minister Alain Jupp and reinforced by Sarkozy, is bent on a judicious and measured revival of French interest and influence in a region which Paris once dominated but had appeared to let slip. For France’s happy interventionists, the prize is La Francophonie redux.

— Guardian News & Media Limited