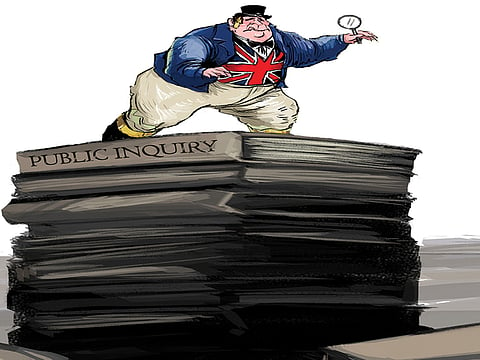

Britain’s got too many inquiries. This calls for an inquiry

This coalition government in the UK has set up inquiry after inquiry because someone or other has shouted for one

‘We want the truth.” That is what people say when they call for inquiries into conflicts, catastrophes or scandals. But how is the truth to be established? About that, people are often impatient and confused.

“What is truth?” Pontius Pilate asked Jesus, but he had him put to death without waiting for the answer. I expect I am in a minority, but I felt a surge of sympathy when I watched Sir John Chilcot appear before the Commons Foreign Affairs Committee on Wednesday.

His report on the Iraq war has taken a shockingly long time to appear, and so MPs and media were baying at him. Their implication was that he did not much care, and was therefore either complacent or covering up. A different explanation struck me: Sir John does care about the truth, and that is why he is taking a long time. He is examining a nine-year period of extremely complicated policy, diplomacy, terrorism and war. He has had to struggle for more than a year to prise key documents (the Bush-Blair exchanges) out of an originally reluctant Cabinet Secretary. Parliament had asked his committee for a reliable account, he said: that is what he will give it.

Some on the committee asked why he could not give a separate, interim report on the run-up to the war, and do the rest later. This was a coded way of saying: “Tell us that Tony Blair lied.”

Sir John answered that you cannot form fair conclusions until you know the full sequence. It is also unjust to tell witnesses what you propose to say about them (by the process known as ‘Maxwellisation’) but give them only one part of the eventual report. How can they comment on a partial charge-sheet?

He said something important. “The more you read, the more lines of inquiry arise.”

This was not the voice of the “establishment”, but of the historian. (And unfortunately the inquiry is one historian short because of the long illness and sad death this week of its member, Sir Martin Gilbert, the biographer of Winston Churchill.)

My fellow-feeling for Sir John arises partly because of my own situation. In 1997, Lady Thatcher asked me to be her authorised biographer, and gave me full access not only to her papers but also to interview her and her associates. Access to government papers followed. Since then, there has not been a day spent on the book when I have not experienced the Chilcot problem — a new document, a new witness (150 in his case, about 500 in mine), and therefore a new line of inquiry.

The truth is almost literally never what you first thought. Neither he nor I have, ahem, quite finished yet. So when aggrieved people demand that inquiries should have access to every document and have the right to compel witnesses, they should be careful what they wish for.

They are looking for a headline, for “justice” or revenge, even, in some cases, for a criminal trial. Instead, they will get, one day, the most conscientious account of what happened, which they may find disappointing. On the same day that Sir John appeared before the committee, it was announced that a new person had been chosen to head the inquiry into historical child abuse allegations which has so far jettisoned two chairmen before hearing a single witness.

The brave woman stepping forward is Justice Lowell Goddard, from New Zealand. What she says is sensible, especially about the need to “scope” the inquiry. But she will be running it under the Inquiries Act of 2005 — judge-led, lawyered up, and therefore, given the vastness of the subject, slow and expensive.

I doubt if this necessarily highly formal process can bring the sort of comfort to victims which the more low-key panel system, as used in the Hillsborough case by Bishop James Jones, was able to offer. The lobby groups and Left-wing lawyers who are longing to expose the entire Thatcher era as institutionally paedophile have shown hubris in seeking to prove “systemic” wrongdoing. Once again, they will get history, not political warfare.

Well, as one who has a vested interest in history, perhaps I should not complain. But I do wonder if this is the best use of taxpayers’ money and officials’ time. Surely it is not the task of government to pay committees to write what amount to enormously expensive and cumbersome history books about whatever has gone horribly wrong (though when I am Sir John Chilcot’s age, I shall be available for such offers). The problem lies in the terms of reference.

Sir John revealed to MPs that it took him 10 minutes to accept Gordon Brown’s request to chair the Iraq inquiry. No doubt he accepted because he is a dutiful public servant and the then prime minister was in a hole. But the speed of decision demanded shows the vast mismatch between the short-term political imperative of Brown and the breathtaking scale of the task he set — to investigate everything politically, diplomatically and militarily related to the invasion of Iraq and what happened afterwards.

Ten minutes for what will, by the end, have taken almost 10 years. The same applies to Theresa May’s frenzied desire to avoid being accused of complacency about child abuse. The inquiry’s terms of reference are as wide as the ocean, but the Home Secretary’s political window to announce the inquiry was as narrow as an arrow slit: hence the rush and bungling over the chairman.

Getting absolutely everything inquired into is a way of getting nothing settled: it is a cop-out. Surely we should be looking for wrong to be identified and lessons to be learnt, when the events are still fresh in the mind.

This coalition Government has set up inquiry after inquiry because someone or other has shouted for one. The trend follows the example of Northern Ireland, where we have let extremists poke their noses, with official help, into everything that our own security forces ever did. It is intensely unfair to those who did dangerous work protecting the public.

It is a symptom of a governmental system which has lost its esprit de corps. It puts itself, almost literally, in the dock.

What is actually, truly useful? As well as Sir John’s evidence and Justice Goddard’s appointment, this busy Wednesday also saw publication of something else. The inspector’s report by Louise Casey on Rotherham council’s governance in relation to child sex abuse (eg how the council licensed, or failed to license, taxi-drivers) was published.

This arose from the independent inquiry by Alexis Jay into the abuse itself, which she began in October 2013 and published in August last year. Now it may be that this inquiry and this report will not be the last word on the subject. I wonder, for example, if it will turn out that the Pakistani-origin gangs who abused white girls also abused girls of their own race, but terrorised them all into silence.

I also have a feeling (because there are two sides to any argument) that the Rotherham Labour councillors so fiercely attacked by Louise Casey deserve a bit more right to be heard. But what is clear is that this sequence is an example of an inquiry process that can get things done.

Jay set out the terrible things she thought had happened. Casey examined how the council had failed to respond to the report they had themselves commissioned. Eric Pickles, the Communities and Local Government Secretary, is sending in commissioners to sort the council out. An inquiry, followed up, has led to action. This process has taken less than 18 months. The subject — though God knows it was obscure and revolting — was not so big that it could not be gripped. Time, perhaps, for an inquiry into inquiries — which work, and which don’t.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2015