Soaring unemployment fuels south Iraq protests

Jobless rate is 11.2%, but it’s twice that in areas that were once controlled by Daesh

Baghdad: For more than three years after graduation, Karar Ala’a Abdul-Wahid tried to get a stable job in the Iraqi government and in the private sector — to no avail.

He once was offered a job with the oil ministry in his energy-rich hometown of Basra, but it came with a hefty price: He would have to pay a bribe of $5,000, which he couldn’t afford.

“Every place has a copy of my resume attached with a request for job,” Abdul-Wahid, a graduate of the Basra Technical Institution, told The Associated Press by phone from the southern city.

“If you are well-connected mainly among political parties and have money, you will get any job you dream of,” Abdul-Wahid said. “If not, you will get nothing.”

Mismanagement since the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq that toppled Saddam Hussain has increased joblessness nationwide. In more recent years, idle young men were lured into the ranks of militant extremists, and now unemployment is fuelling violent protests in the capital of Baghdad and the Shiite heartland in the south.

Demonstrations involving thousands of people broke out this month in Basra province, protesting the lack of jobs and poor public services, including frequent power outages.

According to the World Bank, the overall unemployment rate in Iraq stands at 11.2 per cent and is nearly twice that, 21.6 per cent, in areas that once were under Daesh control and endured heavy destruction from military operations that officially ended late last year.

As of 2014, the poverty rate increased from 19.8 per cent in 2012 to an estimated 22.5 per cent, it added.

In Basra, a city of more than four million, the unemployment rate shot up sharply to at least 30 per cent, according to deputy governor Dhirgham Al Ajwadi.

Between 30,000 and 35,000 students graduate from the city’s private and government universities and institutions, and most of them end up without jobs, he said, blaming federal officials for not focusing on what the labour market needs.

The Basra protests have spread to other cities and threatened to paralyse the oil industry, the lifeline of Iraq’s economy. They have derailed traffic at main ports on the Arabian Gulf and neighbouring Iran and Kuwait.

To contain the unrest, the federal government promised an urgent allocation of 3.5 trillion Iraqi dinars (Dh11.01 billion) for electricity and water projects, as well as 10,000 jobs.

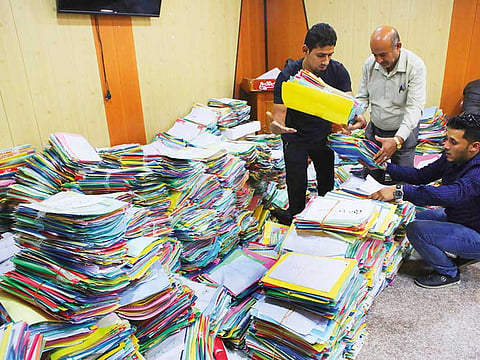

But the requests for jobs exceed that number, with more than 85,000 people applying so far, Al Ajwadi said. “Till now, there is no plan on how and when this will be implemented.”

Unemployment has been one of the thorniest issues for the government, with 70 per cent of Iraqis under age 40 looking for work.

The eldest of six children, the 26-year-old Abdul-Wahid has taken a series of unstable jobs since 2015 to help his family. But he recently got an idea he saw while surfing the internet: selling hot and iced drinks around the city from a vehicle.

“I liked it because it’s something new and no one did it before in Basra,” he said.

He borrowed money from relatives and friends to buy and modify a small car. Then approached a coffee-machine supplier, which helped him with a free machine and discounts on supplies.

He now roams Basra’s streets, offering various types of coffee, tea and other hot and cold beverages. He makes around 900,000 Iraqi dinars a month.

Abdul-Wahid considers himself lucky, because his peers are forced to take menial jobs despite their education.

“There are graduates who work as accountants in small business or construction workers or cleaners in hospitals or security guards in malls because they want feed their families,” he said. “The situation of youth in Basra is miserable.”

He lamented that Basra is seen as “the mother of wealth” because it has about 70 per cent of Iraq’s proven oil reserves of 153.1 billion barrels, along with its ports.

“When we think of all the wealth we have, we feel sad and upset. We deserve to live a better life, not only compared to other Iraqis but compared to the world,” he said.

Iraq suffered a double shock in 2014, when militants from Daesh swept through areas in the north and west and the price of oil plummeted on international markets. Oil revenues make up nearly 95 per cent of the federal budget.

That forced the government to stop hiring and to divert much of its resources to the costly campaign to battle the militants, severely affecting job creation, the private sector and investor confidence. As a result, growth has been stunted, with poverty and unemployment on the rise.

Among Iraq’s many unemployed is Ali Fadhil Kadhim, a 25-year-old graduate with a degree in science and physical education who has taken part in the Basra protests.

Like others, he has applied for jobs but is not optimistic.

“These promises are just anesthetisation for the people and to keep them silent,” said Kadhim, who has worked as a security guard, construction worker and taxi driver. “We started a revolution and we will not give up.”