In a way, sport helped Stockholm clean up its act. While the city never did host the 2004 Olympics (the torch went to Athens), it was voted the European Green Capital of the Year 2010 after the Olympic village that never was became one of the most sustainable urban developments in the country.

The European Green Capital award was conceived to promote and reward these local efforts after the 2006 memorandum signed by a number of European cities encouraging the European Commission to establish such a competition.

Hammarby Sjöstad, the sustainably revamped intended-"Olympic" district, is just one example of Stockholm's raging success in reducing pollution and waste while boosting its economy at the same time.

The award is intended to encourage cities to become sustainable, increase income from eco-tourism and raise their international profile. Other economic benefits will surely follow.

Picked from a total of 35 entries, Stockholm came out on top for sustainable land use, waste management and contribution to fighting climate change.

But 30 years ago, the city told a different story. "The water was filthy and there was no swimming or fishing," said Annika Raab, project manager at the City Hall's executive office. "Now waste-water treatment has improved so much that during the general elections, politicians go and take a sip of water from the lake to prove a point. It's tradition," Raab said.

It is doubtful that politicians in France or the United Kingdom would take a sip of the Seine or the Thames.

Yet waste-water treatment is just one of the feathers in the city's cap. By setting up district heating, a congestion tax in the centre of Stockholm for vehicles and powering public-transport buses with biofuel, carbon dioxide emissions have been reduced by 25 per cent per resident in the past 15 years, said Raab.

By 2050, Stockholm aims to be fossil fuel-free and has been moving towards this goal for years.

Since the 1960s, waste-water treatment facilities have been expanded to all developed areas and sludge is now also an important resource of biogas production.

Construction of the city's first district heating system began at the end of the 1950s and since the mid-1960s, oil and coal have been gradually replaced with biofuel.

Waste-sorting began in the 1970s and now includes glass, plastic, paper, cardboard, metal, electronics and chemicals.

"There was huge opposition to the congestion tax initially but now the majority of people are in its favour," Raab said. And it shows in the city's emissions. In 1990, carbon dioxide emissions per person were 5.3 tonnes annually. In 2000, this had dropped to 4.5 tonnes and in 2005, to 4 tonnes per capita. The next target is for each person to produce only 3 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year by 2015.

Despite the environmental zeal of the country, it remains a far cry from being any kind of Utopia, said Raab. "These accomplishments are within the reach of any city to achieve if they work in a goal-oriented manner," she said.

As part of its 2030 vision, Stockholm has set itself yet more goals. "There are three themes for the city — to be versatile and full of experiences, to be innovative and growing and to be a city for its citizens," Raab said.

In line with this, Stockholm is planning to have the world's biggest fibre optic network to ease the life of each Stockholmer, which, in turn, will reduce traffic by providing the tools for people to be able to work from home. Civic e-services will be available online, including the ability, for example, to book your wedding via the City Hall website.

Hammarby Sjöstad used to be a lot of things. It used to be polluted. It used to be an industrial estate. It had factories and buildings without any licence. Environmentally, it was a nightmare. So when Stockholm put in a bid to host the 2004 Olympics, Hammarby Sjöstad as it was had to go.

The area covers two square kilometres and is now home to 25,000 people, of mainly young families and urban professionals. Fifteen years ago, no parent would have let their children run around in this area. Rusty cars dotted the landscape when they weren't tipped into the lake and canals.

Malena Karlsson, a guide at the area's information centre, hosts groups of pupils and city planners alike at Hammarby Sjöstad on a near-daily basis to explain the mammoth task that has been at hand since 1999. The entire project will only be completed by 2018.

“It was not an environmental sustainable area. There was so much seepage into the ground from the factories that 900 thousand tonnes of soil had to be removed and cleaned,” she said.

“Four hundred thousand tonnes of soil was put back to form the ski slope here.”

A total of 30 developers grouped together to design the city – something of a rarity in most city planning efforts.

“We expected a population of people aged 55+ to come and live here, but young families with kids started moving in. There are actually not enough schools so more kindergartens and pre-schools are being planned to meet the demand,” said Karlsson.

Renovation of Hammarby Sjostad has taken an investment of between three and four million euros, she added. The area has a residential area of 11,000 flats of which 54 per cent have been bought and 46 percent are rented. All the ‘white goods’ such as washing machine, dishwasher and fridge are already installed in each property and meet high-efficiency criteria.

“Seventy five percent of the environmental solutions are built into the buildings, but residents need to do the remaining 25 percent through their efforts,” said Karlsson.

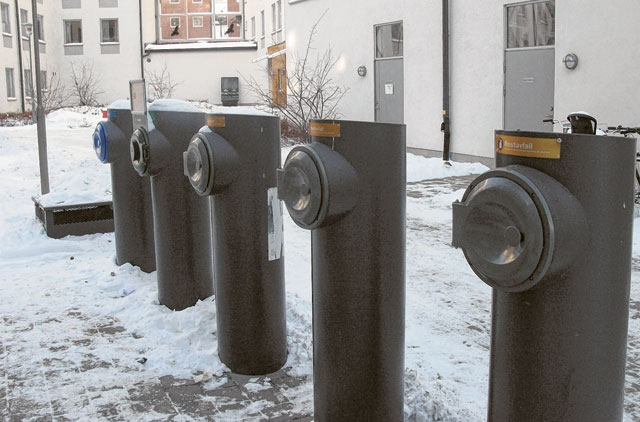

The most innovative is the waste disposal system. Ten percent of Stockholm’s waste comes from Hammarby Sjostad. Instead of collecting rubbish bags by hand and transporting them in loud early-morning trucks, all waste is sorted at the source and dropped by residents in chutes where powerful airflow carries the waste underground and straight to the disposal site. Ingenious.

Vacuum waste management

You probably never imagined your rubbish traveling below ground at speeds of around 70km an hour. This new and cleaner way of collecting household waste exists not only in Hammarby Sjostad but in hundreds of city districts around the world.

Envac is an automated waste collection vacuum system. The concept is the use of underground pipes to transport waste by letting air do the heavy lifting.

Reception centres are located outside the outskirts of the area where lorries can access full containers without any problem and transport waste to recycling centres, landfill or incinerator.

Dubai narrowly missed out on having such technology linking up Jumeirah Beach Residence towers, and the hotel strip of Sheikh Zayed road. Such a system could still be implemented in a ‘finished’ city but works best as an integrated solution penciled into city plans from the beginning said Christer Ojdemark, chief executive officer of Envac.

“In Sweden it’s illegal to have waste in the street, it should be kept inside appointed rooms in apartment buildings or in homes,” said Ojdemark.

As many factions as needed can be built it: for food waste, paper, or for the incinerator which makes sorting waste at the source much easier.

“We have bins in courtyards that take up 1 metre-squared. For buildings in old cities, such as Barcelona where we cannot go into the buildings, we can put the chutes on the street without taking up space,” he said. “Where skyrise buildings are, the better the systems can be incorporated.”

Waste management, like electricity and water, should be part of the utilities of any city, he added.

Once deposited in the chutes, the waste is stored for a short while on a valve which opens for an hour, two to three times a day and sucks the waste away. Fans create the partial vaccum that sucks the waste to the collection station.

“Bins like this never overflow,” said Ojdemark. The Emirates flight kitchen is equipped with vacuum system for all the food waste coming off the flights. Up to 60 tons of waste is thrown out daily using this system. The new fish market in Sharjah will also have an Envac system to rid the area of waste fish products, he said. The waste food vacuum is a very niche market and is currently in 45 airports. The first system was installed in 1971 in Orlando Disney World.

“Our main goal is to collect the waste. It depends on the municipality facilities if extra factions are built to aid waste separation. In Spain, like Stockholm, the system will have up to four factions,” he said.

Waste is only energy

More than sixty percent of household waste in Sweden is used for energy production by incineration. Each year 235 000 tonnes of waste is incinerated with energy-recovery, however Swedes are not producing enough combustible waste and the total capacity for energy-recovery at the incinerator-plant Högdalenverket is 770 000 ton per year.

Jens Bjöörn, head of communication and sustainability for Fortum which manages the city incinerator in Stockholm said the heat produced from burning waste provides electricity for 200,000 household and heating for 80,000 households.

“We are moving towards the tipping point where the consequences of our actions are unacceptable. Do we really need to change? Even if we don’t agree, we still have to be more sustainable,” said Bjöörn.

The facility consists of six furnaces for waste combustion, two oil-fuelled furnaces for top loads and two steam turbines for electricity production. The maximal heat power is 385 MW and the two turbines together provide 71 MW of electricity.

Combusting household waste is a way of producing energy from by-products that lack alternative use. The climate impact is low and large waste deposits, leaking methane and heavy metals, are avoided. Compared to depositing sorted household and industrial waste, combustion actually has a smaller effect on the climate, since the process is controlled and the flue gases are cleaned extensively, said Bjöörn. In addition, the use of fossil powered power plants can be reduced, which offsets emissions of fossil carbon.

“We can remove all heavy metals in a controlled process, by putting it in concrete blocks so it does not leach,” he said.

Reuse and recycle of course

Each Swede produces on average 480kg of waste annually, a relatively low amount compared to Abu Dhabi’s annual average 730 kg per person, with Dubai following closely at 725 kg. Yet for the Swedish Environmental Protection agency, even this is too much.

Hans Wrådhe, head of product and waste unit at Swedish EPA said most people follow the guidelines for sorting waste at home but it is impossible to reach 100 percent of citizens.

However recycling rates in Sweden are staggering with an impressive 94 percent of recycling for glass, 91 percent for aluminium cans, 84 percent of PET plastics, 74 per cent of papers and cardboard, 67percent non aluminium drinks containers, with just a low 31 percent for non-PET plastic.

“The ever growing waste amount is a big worry. Minimizing waste will be included in new EU directives that each country should have programmes for treating and sorting waste,” he said. “I don’t know how we manage to achieve these results though. I don’t know how people are encouraged to recycle. There is a history of respecting the environment and protecting our resources.”

Infrastructure probably has something to do with it though. Bromma recycling plant is one of the biggest recycling centres in Sweden where citizens come and drop off their household recyclable and hazardous waste, with no prizes, cash giveaways or raffles to incite people to take care what they do with their waste. They just do it.

There are several outlets for them to use including public collection-points. mobile telephone collection, paint-shops take back old paints and thinners to avoid them being tipped into the waste water systems and toilets, pharmacies take back old medicines and

battery collection-points are in most high-frequency areas. Stockholm alone has five recycling-centres that are open 8 hours, 359 days a year.

Nils Lundkvist, manager technical strategy at Traffic Administration at City Hall said around 275kg per person goes to the incinerator annually. “There is less than a 1percent increase annually but flows change where recycling increases but incineration decreases,” he said. A legislation was passed where recyclable materials likes glass, paper or board, newspapers and metals were the producers responsibility to recycle, taking a big burden off the municipality, Lundkvist added.

“In 2010, 16kg of electrical waste was produced per person. Our EU goal is minimize this to 4kg per year. Because of the legislation of producers to recycle, the electronic waste is not sent to developing countries to recycle it is done within Sweden or within the EU if a plant is better equipped than a Swedish plant.”