Victoria Beckham never claimed to be the best singer in the Spice Girls, or the best dancer either. Nor was David Beckham necessarily the greatest footballer ever to wear a Manchester United shirt. The team’s former manager Alex Ferguson once said he had only ever worked with four world-class players, and didn’t include Beckham on his list.

Yet, by dint of hard work, strategic decision-making and a remarkable ability to stay likeable even while becoming preposterously rich, the Beckhams have achieved the goal Victoria identified back in 2001, when she wrote of wanting to be “as famous as Persil Automatic”. They have evolved beyond mere celebrities into a fully fledged brand, a household name as familiar and comforting as your daily breakfast cereal or family car. What they seem to have understood is that fame comes and goes, but brands have the power to get inside your head.

CELEB INFLUENCERS

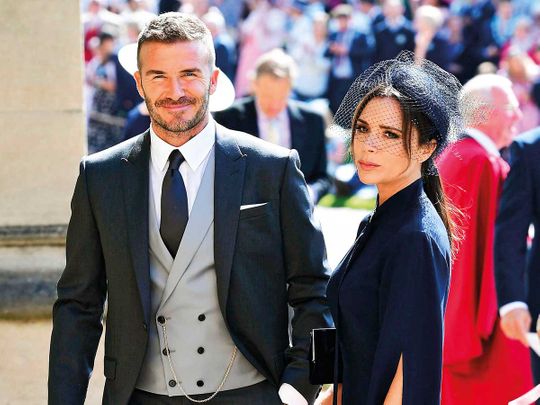

In July, it will be 20 years since Victoria Adams married David Beckham in a ceremony that OK! magazine paid an undisclosed sum to cover. They had met in 1997 at a charity football match, although each already had their eye on the other. (As David noted in his autobiography: “My wife picked me out of a soccer sticker book. And I chose her off the telly.”) Within two years they had got engaged, had their first son, Brooklyn, and married; it was shortly after the wedding that the red tops coined the phrase “Brand Beckham”, describing the way each boosted the other’s already significant pulling power.

“When he and Victoria first got together, they were the first celebrity couple you could have on both back page and front page. There wasn’t a part of the paper they couldn’t feature in, a conversation that you couldn’t find a way of fitting them into,” says Andy Milligan, founder of the branding consultancy The Caffeine Partnership and author of Brand It Like Beckham. The timing was perfect — just as football was evolving from a sport into what Milligan calls a “24/7 entertainment business”. From the start, both partners embodied not just glamour but the highly appealing values of groundedness and hard graft. He was the son of a gas fitter, who worked his way up in football through the academy programme; she turned out to be just as driven, doggedly establishing an unexpectedly credible new career in fashion when the Spice Girls folded rather than remain a football Wag.

“The reason we all love Victoria Beckham is that she’s the queen of reinvention,” says Hattie Brett, the editor of Grazia magazine. “She’s constantly doing new things: establishing herself as a designer, bringing out a childrenswear collection, adopting new tech.”

But it’s the licensing and sponsorship deals using David’s name and image that have quietly proved the money spinner. Earlier this year, the Beckhams officially became dollar billionaires, thanks in part to the lucrative corporate tie-ins covering everything from watches and whisky to pants and skincare that David has amassed since retiring from football in 2013. (Her fashion label, Victoria Beckham Ltd, launched in 2008 and has yet to turn a profit, although that’s not unusual in fashion.) They may not be in the Kardashians’ financial league, but as Milligan puts it, “the Beckhams are a really good, British branded business that doesn’t get the credit for its exports. It’s a company whose core value is intellectual property.”

MAINSTREAM CULTURE

Yet the idea the Beckhams pioneered, that a person could become a brand, has filtered down into mainstream culture. Instagram has turned millennials into curators of their lives for public consumption, anxiously presenting an idealised version of themselves at all times, while professional “influencers” now hire brand managers to protect the image on which their whole commercial edifice rests. At work, Generation Z are told to define their “personal brand” if they want to get hired, promoted or simply noticed in a precarious and crowded freelance world.

As Jennifer Holloway, a personal branding expert who works with blue chip clients from RBS to Asda, puts it: “People buy people. No matter how good you are at your job, if I haven’t bought into you as a person — if I don’t like you and trust you — it isn’t going to work.”

And above all, good personal brands are ruthlessly consistent. They stick to the values they originally embodied, while moving gently with the times (think of the 2006 Victoria Beckham, all hot pants and hair extensions as she watched her husband in the World Cup, versus the pixie cut and chic high necklines in which she relaunched herself as a fashion designer two years later).

When Holloway started out, the emphasis was on CEOs and senior executives wanting to hone their public personas. But these days she is increasingly asked to work with young graduate trainees on making good first impressions, although she thinks branding really comes into its own as organisations begin identifying high-potential employees for promotion. “It irks me, as a female, that women will often rely on: ‘I’m doing a good job and that will get me noticed’, where men are much better at: ‘I’m going to get noticed.’”

What she is describing is arguably a crisply articulated, slicker version of professional reputation-building rather than a brand in the Beckham sense — the latter being essentially a vast international network of trademarks and intellectual property deals, designed to protect and monetise the appeal of a name. Yet even this level of self-promotion makes some people balk, just as some balk at paying over the odds for something just because it has a celebrity’s face on the packaging.

BRANDING BACKFIRING

Scarlett Dixon was 17 and hoping to become a journalist when she first started a lifestyle blog. But as her follower numbers took off and companies started approaching her with freebies in return for promotion, she eventually abandoned the journalism to go full time as a blogger and influencer. As @scarlettlondon, she is paid to model and plug products on her social media channels; she has, essentially, turned an idea of herself, projected online, into a trusted brand that can then sometimes partner with other brands to mutual advantage.

Even the sunniest of brands, however, face storms. Last year, a paid ad Dixon did for the mouthwash Listerine, featuring shots of herself supposedly eating pancakes in bed, went viral for all the wrong reasons. Things escalated to the point that Dixon — only 24 at the time — ended up receiving death threats. She won’t talk directly about what was clearly a painful episode, but agrees that online negativity is an unwanted by-product of the job: “It’s definitely difficult to watch a character assassination of yourself take place online, by strangers who do not know you. I do think we all need to be more aware about what conversations we are partaking in online. It’s all too easy to forget that there are real people behind every viral storm.”

And that is one downside of turning humans into products: consumers may begin treating them as if they really are products, disposable or impervious to hurt. When rumours swept the internet last year that the Beckhams were about to divorce, speculation immediately centred on what it meant not for them or their four children but for the brand, given that David’s marketability still rests on being seen as a devoted husband, father and general nice guy.

Since the rumours turned out to be false, we will never know. Yet it was a timely reminder that, unlike Persil Automatic, people have feelings. Their lives can take unexpected turns, which most definitely aren’t on brand; they may get burnt out, or simply stop wanting to live in a goldfish bowl round the clock.

And, in that light, it is perhaps significant that David Beckham and his long-time manager Simon Fuller (who originally founded the Spice Girls and whose company, XIX Management, owns a third of the Beckhams’ family company, Brand Beckham Holdings) recently signed a deal to develop branded products for other sports stars, which would ensure it doesn’t always have to be David’s face on the packaging and his personal life on the line. If even Brand Beckham has begun to plan for a future life behind the camera, rather than always having to be in front of it, that really would be the end of an era.