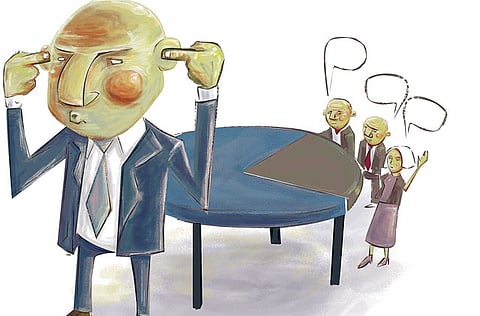

Majority rule, minority plight

Analysts believe changes in law and culture hold key to shareholder activism

Dubai: When Al Kharafi Group joined hands with other investors to sell majority stake in Zain, leading Kuwait's telecom giant to offload its Africa operations, it once again brought into focus the issue of dominant shareholder's relationship with management and minority investors.

It showcases, according to observers, how the majority group can decide the affairs and direction of the company against the professional guidance and opinion of the management. Also, importantly, it shows how minority shareholders, without sufficient legal protection, are almost disregarded in the decision-making process.

The rift between the Al Kharafi group and the management, especially the outspoken CEO Sa'ad Al Barrak, who, through acquisitions over the years, had built Zain into one of the largest telecom companies in the region, seemed to have been over the future direction of the company.

Al Barrak resigned. Or, as some feel, he was shown the door.

"It was [in case of Zain] basically the controlling group of shareholders who had a different vision for the company that prevailed," said Shakeel Sarwar, head of asset management at Securities and Investment Company (SICO), Bahrain. "So at times what is best for the company may not happen because the dominant shareholders have a different interest in the company."

This controversy had a familiar refrain to it, peculiar to the region, Sarwar added. Kuwait Projects Company Holding's (KIPCO) selling of its majority stake in National Mobile Telecommunications Company (NMTC) to Qatar Telecommunications (QTEL) is one more example of the major shareholder's power to decide the fate of the company.

It's not just the structure, say the observers, but the prevailing culture of business with very little legal cover for minority shareholders within the company framework that allows the majority group getting away with its behaviour. The culture of passivity of minority investors is to blame too.

Looking at the shareholding patterns, it is clear that most companies, listed or otherwise, are either controlled by government or powerful families. And at times, the controlling shareholders have several different business interests and cross holdings that they may not always take into account the interests of the company in question, or for that matter, minor shareholders. And not to forget, the free floats in case of listed companies are relatively so small that it makes minority investors, including institutional ones, disinterested.

In some cases even the dominant shareholder — the individual or the family — or their friends are involved in the management, occupying top management positions. At times, you even have the board members, because of their power, actually becoming the CEOs running the companies.

In contrast, in the West, most of the listed companies have a fragmented shareholding base. Even the founders in the large institutional invested companies together would not probably be accounting for more than 15 to 20 per cent.

In that type of an equation in the West, "management becomes very powerful", Sarwar pointed out.

"In order to control the management, there the shareholders have to be active and united," he added. "For that they form lobbies and groups. You do see at times hostile takeovers happening with the management being changed. Differences crop up often between shareholders and managements because managements are very powerful."

The minority shareholders of the region, who are largely retail investors, are to blame too, observers said. They have a short-term horizon and do not much care for the strategy and vision issues of the company.

Short-term gains

Where retail investors have objected or raised issues, it had more to do with short-term gains. In 2007, investors were agitated about Emaar Properties' announcement of 20 per cent dividend, demanding more. They were least interested on Emaar's business path and strategy, at home and abroad.

"There is no sense of business ownership in minority shareholders," said Sarwar. "Accordingly shares are often purchased with an eye on near-term profitability and dividends than having an eye on the USP of the business."

The dominant shareowner's powerful position is also an issue that makes others reluctant to be active.

"Because the controlling shareholders are generally so powerful, there is a feeling you don't want to cross swords with them who seem to have a presence on a significant number of boards and whose interests are not altogether transparent," Sarwar said.

With private equity firms becoming more active in the region, there are signs that they are taking a more proactive approach. Saffar Capital, a boutique private equity firm with 60 per cent stake in Zawya and 11 per cent in Credit Suisse Saudi Arabia, is one which adopts such an approach, according to one of its senior officials.

Sabah Al Binali, principal and chief investment officer, is chairman of the Board of Directors on Zawya, and a director on the Board and a member of the Audit Committee of Credit Suisse Saudi Arabia. He advocates activism, especially when it comes to managing relationship with the Board of Directors to get the desired results.

"Shareholders need to manage the Board of Directors, and it is the Board who oversees management," he said. "In general, shareholders need to be much more active in holding the Board of Directors accountable, and demanding change when the Board fails in its duty or performance."

He added: "Shareholders only have a responsibility to themselves. It is their money, and if they do not try to look after it by holding the Board of Directors accountable, then they only have themselves to blame if they lose money due to mismanagement."

Even the institutional investors, which, in many cases, have a small representation in listed companies, have very little say in the operations of the company. Even those which have a larger representation, like some of the pension funds in Bahrain, Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, Sarwar pointed out, remain quiet.

In this regard, the existing laws, especially the Companies Act, are insufficient to provide protection to minority investors and requires immediate reform, according to Dr. Nasser Saeedi, chief economist at Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC).

"That's one major issue and we have been advocating reform for that for a long time for increasing protection of minority shareholders and we believe that should happen not only for listed companies but for any private company," he said.

Specifically, when it comes to development of take over and merger codes, the region lags behind, Sarwar said. "And with majority shareholders dominating management in many cases, it has an adverse effect when companies are acquiring businesses. They are paying a huge premium over the market price with no one to question them."

Saeedi pointed out that it's the very lack of enough institutional investors that is in itself a reason for lack of shareholder activism. "To improve shareholder activism and strengthen it, you really need institutional investors," he said. "So you can well imagine the position for an individual investor who might be a small shareholder to become very active. It is expensive, they have to be really informed, and they may not be listened to, especially if the laws don't provide sufficient protection."

The problem lies with the structure of the region's markets. Some of the markets are closed to international institutional investors. And the classification of the region's markets as "frontier" and not "emerging" discourages most of such investors. So what happens, instead, is hedge funds flock here, which, for their own obvious reasons, have a short-term investment horizon.

"They [hedge funds] are not in there for the long-term," said Saeedi. "They are not in there to see you grow and improve your corporate governance. They are in there to make money and get out," he said.

That would mean increase in the onus of existing institutional investors — be it pension funds, private equity groups, insurance companies and mutual funds — to be more active on the boards.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox