COVID-19: How the coronavirus affects people with bleeding disorders

The risk of COVID-19-related complications does not increase for haemophilia patients

Also In This Package

Pictures: Dubai summer festival is in full swing

Asian countries resume lockdown as infections spike

Look which European leader wears the mask the best

Look how American schools plan for a September restart

COVID-19: Indian stars and their brush with the virus

Eid Al Adha: COVID fears forces animal sellers online

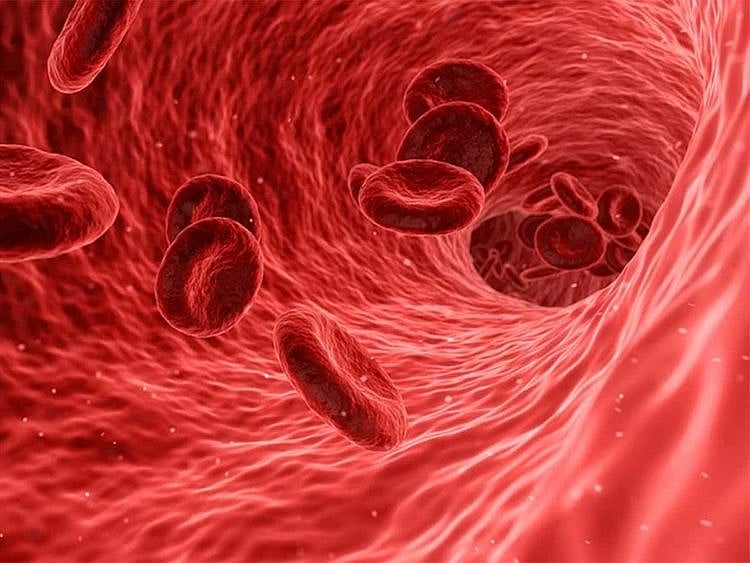

Blood clotting is a leading cause of deaths in COVID-19 patients. What happens to people whose blood doesn’t clot easily? How does the coronavirus infection affect people with bleeding disorders like haemophilia?

Haemophilia is a condition that results in abnormal bleeding in a wound due to reduced clotting. Internal bleeding can be fatal if it occurs within a vital organ, especially the brain.

Also Read

COVID-19: Tourists touch down in Dubai boosting confidence in the travel market COVID -19: Drive-in boom in post coronavirus pandemic world COVID-19: In pictures, Dubai residents get in to regular work mode Photos: Dubai field hospital bids farewell to last coronavirus patientMedical advisers say the risk for haemophiliacs is similar to healthy people. That is people without any underlying medical conditions. They should follow the guidelines and prevent exposure to the virus.

If a person with haemophilia contracts COVID-19, they should follow the treatments prescribed to healthy people. But if the person is taking immunosuppressants, that would put them in the high-risk category. Also, there is a likelihood of getting acquired haemophilia A (AHA).

Let’s look at the disorder and threats posed by COVID-19.

What’s haemophilia?

Haemophilia is a rare hereditary disorder, generally found in males, that reduces the blood’s ability to clot. People with haemophilia do not have enough clotting factors (most often factor VIII, or FVIII), so they bleed for a longer time than usual.

When injuries happen, blood thickens or coagulates to prevent excessive bleeding through a process termed haemostasis. Blood cells called platelets work with proteins (clotting factors) in blood plasma (the clear liquid) to form a clot over the wound to stop bleeding.

Around 400,000 individuals worldwide are estimated to have the genetic disorder, according to News Medical. It is very rare for a girl to be born with haemophilia. That can happen if the father has haemophilia and the mother carries the gene for haemophilia.

In around 20 per cent of all cases, haemophilia is caused by a spontaneous gene mutation. In these cases, there is no history of abnormal bleeding in the family.

What are the common forms of haemophilia?

Haemophilia can vary in severity, depending on the type of genetic mutation. The degree of symptoms depends upon the levels of the affected clotting factor, and are classified as severe, moderate and mild.

Severe haemophilia represent around 60 per cent of cases. For them, bleeding episodes tend to start early in life, within the first two years.

For moderate or mild cases, symptoms may develop later in life. Moderate disease form 15 per cent of cases and the rest (25 per cent) cases are mild.

Though the symptoms are similar the treatments required are different since clotting factors affected are not the same.

What the main types of blood disorders?

The main types, according to Stanford Health Care, are:

Haemophilia A: Known as classic haemophilia, this is caused by a lack of the blood clotting factor VIII. Around 85 per cent of haemophiliacs have type A disease. Haemophilia A affects 1 in 5,000-10,000 males.

Haemophilia B: A factor IX deficiency causes this disease, which is also known as Christmas disease. Haemophilia B is less common, affecting 1 in 25,000-30,000 males. People with haemophilia B Leyden, an unusual variant, experience excessive bleeding in childhood but have less frequent bleeding problems after puberty.

Haemophilia C: This term refers to a lack of clotting factor XI Haemophilia C is a mild form of the disease that’s caused by a deficiency of factor XI. People with this rare type of haemophilia often don’t experience spontaneous bleeding. Haemorrhaging usually happens after trauma or surgery.

Von Willebrand disease: This is not strictly haemophilia, but it’s a mild bleeding disorder. In this condition, a part of the factor VIII molecule known as von Willebrand factor or ristocetin cofactor is reduced. The factor helps the platelets cling to the lining of a vein or artery, and that’s crucial to clotting. Its absence results in prolonged bleeding.

What’s acquired haemophilia?

This is not one of the main types of haemophilia since it not caused by inherited gene mutations. This rare condition, usually witnessed in adulthood, is characterised by excessive bleeding into the skin, muscles, or soft tissues.

Acquired haemophilia results in autoantibodies attacking and disabling the coagulation factor VIII. These autoantibodies are usually associated with pregnancy, immune system disorders, cancer, or allergic reactions to certain drugs. In many other cases, the cause is unknown.

AHA tends to occur in the elderly, even those who do not have underlying medical conditions.

What are the symptoms of haemophilia?

The main symptom is prolonged bleeding. Some of the main symptoms are unexplained nose bleeds; excessive bleeding from cut and injuries; bleeding gums; skin that bruises easily; pain and stiffness of joints (due to internal bleeding).

How’s haemophilia treated?

The treatment depends on the severity of the condition. The two main approaches are preventative treatment and on-demand treatment, according to Britain’s National Health Service.

Preventative treatment: Clotting factor medicine is regularly injected to prevent bleeding and damage to joints and muscles. Most cases of haemophilia are severe and need preventative treatment. Preventative treatment is usually life-long.

On-demand treatment: where medicine is used to treat prolonged bleeding

What are the complications of haemophilia?

The risk of developing inhibitors in your immune system and joint problems are among the complications found in haemophiliacs.

Inhibitors: These are antibodies developed in the body’s immune system as a result of taking blood-clotting medicine. The antibodies reduce the effectiveness of the medication. People having haemophilia treatment should be regularly tested for inhibitors.

Joint damage: Bleeding in joints can damage the soft spongy tissue (cartilage), and the tissue lining). A damaged joint is more vulnerable to bleeding. Joint damage is more common in older adults with severe haemophilia. Serious injury may mean the joint needs to be replaced.

How to live with haemophilia

Most people with haemophilia can lead healthy lives with the help of medication. They should avoid contact sports, such as football, rugby and games that could result in injuries easily. They should also take care while using other medicines that affect your blood’s clotting ability (aspirin, ibuprofen, etc). Regular dental checkups are a must to ensure that teeth and gums are in good health.

How COVID-19 affects people with haemophilia

Medical professionals say that bleeding disorders themselves do not raise the risk of contracting the coronavirus. But some underlying ailments (comorbidities) could increase the chances of hospitalisation and organ failure.

Patients with HIV (the virus that causes AIDS) and people with inhibitors who are on immunosuppressants are susceptible to complications arising from COVID-19 infections. Otherwise, the virus does not increase the chances of COVID-19 infection for patients with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders.

A COVID-19 infection and its accompanying stress can trigger the development of inhibitors even in patients without haemophilia, the Coalition for Hemophilia B says. So patients have to be continually monitored as previously eliminated inhibitors can to be reactivated.

Is it safe for haemophilia patients to have a COVID–19 nasal/throat swab test?

If there hasn’t been a recent episode of a nosebleed, a nasal swab is unlikely to trigger a bleed. But it’s advisable to inform the medical staff of the bleeding disorder so that they can assess the risk of a bleeding episode.

How COVID-19 leads to acquired haemophilia

A SARS-CoV-2 infection can result in acquired haemophilia A (AHA), Hemophilia News Today reported. AHA is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system produces antibodies that destroy a blood-clotting protein (factor VIII). It leads to blood clotting problems and bleeding that are similar to the symptoms of haemophilia A.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.