Economy: The changing profile

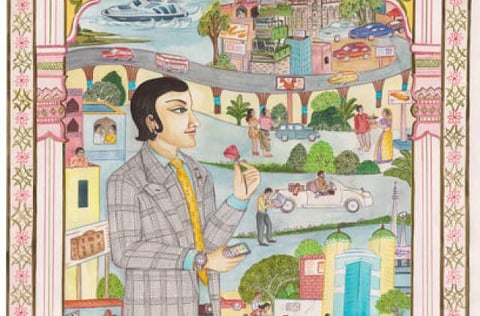

The new Indian, with his growing buying power, is influencing decision-making as the country transforms into a major global player

When it comes to India, they tell you that whatever you can rightly say about the country, the reverse is also true. Recent events have proven this again.

Economically and socially, India is now a major player on the world stage, its vast population creating its own lifestyle influences. Whether it’s business, fashion, sport, jewellery or property, Indians are at the top of the pyramid as change makers, with international brands creating products specifically for Indian buyers, both in the country and abroad.

Thus far, high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) - India has 125,500, according to the World Wealth Report by Capgemini and partner RBC Wealth Management released in June 2012 - have been lifestyle influencers with their buying power.

But today the buying power of the vast Indian middle class (267 million people in the next five years, according to the National Council for Applied Economic Research’s Centre for Macro Consumer Research, up from the current 160 million) is being felt in the construction industry, at duty-free counters and in its increasingly attractive shopping malls.

As the world demands entry into India and every infrastructural bump on the road is magnified and examined in the context of foreign direct investment, India has never been more attractive and the world has never been in a bigger hurry.

Yet, amid this runaway growth story, several challenges must be overcome if India is to achieve its potential and raise its 350 million citizens who still live in poverty — though data released this March by India’s Planning Commission shows that the number of people living in absolute poverty in the country decreased by 12.5 per cent between 2004-05 and 2009-2010.

On the one hand, the return of pro-market Palaniappan Chidambaram to the post of Finance Minister on July 31 — a rather eventful date for India — has put three seasoned economic decision-makers at the helm, including ex-finance minister, President Pranab Mukherjee and Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh, whose previous stint as finance minister brought in economic reforms back in 1991.

In the face of the volatility of economic ratings in current times, combined with the political mayhem that has characterised much decision-making, Chidambaram’s appointment has the markets rubbing hands in anticipation. Within a week of his appointment he said that uppermost in his mind was the duty to regain the confidence of stakeholders and promised measures to contain fiscal deficit and check inflation.

On the other hand, close to his appointment, the RBI lowered its growth projection for the financial year 2012-13 (April-March) to 6.5 per cent from 7.3 and raised its inflation forecast for March 2013 to 7 per cent from 6.5. A failed monsoon, officially declared as deficient, has added to the picture of doom.

Fluctuating ratings

India’s economic popularity, indicated by its ratings, fluctuates like the popularity charts of its film stars. Most recently, global agency Moody’s gave India a thumbs-up on July 25, underlining that the country’s negative economic trends are “unlikely to become permanent or even medium-term features” and the credit rating outlook is stable on India’s current Baa3 rating.

But Moody’s judgement was in the backdrop of two of its rivals — Standard & Poor’s and Fitch — lowering the credit rating outlook to negative from stable. Just about a month ago, Fitch’s ratings for India were BBB — the lowest investment grade. Standard & Poor’s, of course, infamously said that India could become the first of the Bric economies, which also include Brazil, Russia and China, to lose its investment grade status.

The outlook was balanced by the World Bank’s vote of confidence this June that “India will see growth (measured at factor cost) increasing to 6.9, 7.2 and 7.4 per cent in fiscal years 2012-13, 2013-14 and 2014-15 respectively” in its report titled Global Economic Prospects.

The power crisis that had the world media come up with dark headlines left an estimated 600 million Indians without electricity across 20 states on July 31. While the numbers are big, consider this: in times not marked by a power failure, one third of India’s 1.2 billion lack access to electricity.

Commentators at media houses such as CNN are blaming the growing appetite of the rural voters for cheap power and line loss, which contributes to the loss of 30 per cent of the total power produced. These are all linked to infrastructure, touted as the biggest beneficiary of foreign direct investment in any sector and so the biggest stick to beat India with.

Interestingly, also on July 31, Fitch Ratings released its outlook for the Indian power sector, calling it stable, for its private investor-friendly credentials rather than strength. Fitch said, “Substantial hikes in retail power tariffs in some states (Tamil Nadu 37 per cent, Delhi 26 per cent and Punjab 12 per cent) in 2012 were positive signs, indicating the inevitability of passing on increased fuel costs to consumers. The retail tariff hikes have helped the margins of State Power Utilities and thus somewhat restored investor confidence.”

The need for power has brought into focus alternative energy sources. US solar firm SunEdison chose Meerwada village in Gujarat, which lies outside the national power grid, to test out its business models and installed solar panels. The village enjoyed uninterrupted solar power during the blackout.

The Indian Ministry of New and Renewable Energy already encourages solar systems that bypass the national grid. The government offsets 30 per cent of the project cost and even provides low-interest loans for solar power systems under its Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission policy launched in 2010.

Karnataka in the south and Assam in the north-east already have small-scale direct current systems, supplying basic lights and mobile phone chargers at Rs100-Rs200 per month.

Today, more power to Anna is the chant among a large section of India which perceives itself as powerless. Few remember that anti-corruption activist Anna Hazare’s village, Ralegan Siddhi, has long been declared a model village by the World Bank Group, and comes fitted with solar lights. As Anna sets about creating a political alternative, India’s power equation is set to change in more ways than one.

The right policy

As export-led growth comes down further and BPO contracts decline, a failed monsoon may push GDP growth in 2012 well below 6 per cent. In this scenario India’s new finance minister has his task cut out so that no citizen is left behind in the quest for growth. While the world may be in a hurry for India to shape up, the country cannot be on a deadline.

A voice of reason came from a reader on news agency Reuters’ website as a comment on the news of Fitch’s poor ratings. The user RajeevRawatCA wrote, “India must make decisions to serve its unique demographics and resist the temptation of mimicking Western economies. Ratings agencies matter, but less than the government’s own assessment of what’s good for its people and economy. Poor ratings can damage the country’s prospects, but bad policy will damage the country’s future.”

Maybe what seems like contradictions from the outside is really a tough balancing act. More power to India!