Why Turkey’s EU application is gathering dust

Ankara applied to join the bloc 31 years ago, but with tensions running high with Athens, there’s no chance of membership anytime soon

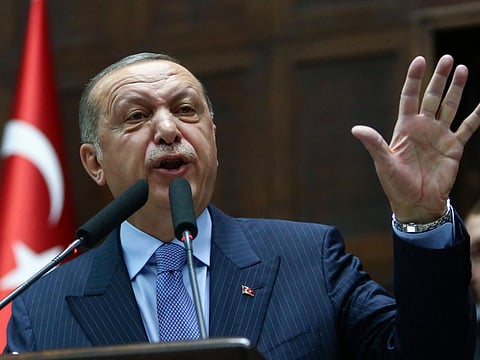

In Istanbul last Sunday, as he detailed his party’s manifesto for elections on June 24, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan told thousands of supporters that Turkey had never given up on its long-standing ambitions to join the European Union (EU) — it’s just that his counterparts in the EU had done everything in their powers to stall that application.

For the record, Turkey applied to join the European Economic Community — the predecessor to the EU — more than 31 years ago. On April 14, 1987, to be exact. It’s just that some matters like the re-unification of Cyprus, strong opposition from Germany and France then, and east European nations now, stood in Turkey’s way. And since 2016, EU membership talks have all but collapsed.

But if Erdogan and Turkey have ever any hope of joining the economic and political bloc that together make up a common market of more than 550 million people across 28 nations in the world’s fourth-largest economy, their biggest obstacle will be their next-door neighbour, Greece. And right now, relations between the two members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) are best described as frosty, with the two neighbours not even exchanging pleasantries.

Just over a day before Erdogan addressed his party supporters, a Turkish cargo ship collided with a Greek warship off the Aegean Sea island of Lesbos. This maritime mishap was the latest to fuel fears that of a dustup in an area that regularly sees naval vessels from both nations square off. The gunboat Armartalos was hit within hours of Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras giving a keynote speech on Lesbos, which remains an epicentre for 9,000 mostly Syrian refugees who fled violence in their homeland.

Tsipras himself received a less than friendly Lesbos welcome, with protests from islanders and business leaders there complaining over the lack of resources for refugees. Across the Aegean chain of Lesbos, Chios, Kos, Leros and Samos there are still 16,000 refugees.

At the height of the refugee crisis three summers ago, some 15,000 people were arriving daily across the short boat trip from Turkey’s coast, and hundreds of thousands took the route as their first point of entry into the EU, where their free movement was supposedly ensured. And we all remember how that turned out, with razor wire and hastily erected frontiers put in their way by Balkan and eastern European states.

During his Lesbos sojourn, Tsipras defended the controversial deal reached between the EU and Turkey to stop the large-scale movement of refugees. That deal basically meant that for every Syrian sent back to Turkey with a rejected asylum application, one other asylum application would be granted in the EU. As a sop to Turkey, the EU also provided €3 billion (Dh13.1 billion) in aid to Ankara to help with refugee costs there, and opened up the Schengen passport-free zone to Turkish nationals. And the big prize? Brussels promised it would fast track Turkey’s application to join the EU. The deal came into effect in March 2016 — and more than two years’ on, that hasn’t happened. Nor will it. And certainly not as long as the Aegean remains a point of tension between Ankara and Athens.

According to the Hellenic Navy, the cargo ship increased speed and made off to Turkey’s nearest coast without responding to radio messages from the Armartalos.

While damage to the warship — part of a Nato-led operation monitoring those illegal refugee flows in the Aegean — was also described as minimal, the incident highlighted the friction between the countries. Nikos Kotzias, Greece’s Foreign Minister, said Ankara had “come close” to “crossing a red line” when a Turkish patrol boat rammed a Greek coastguard ship off a disputed Aegean isle in another incident in February – the same uninhabited rocky islet that almost sparked a war back in 1996.

Erdogan’s Justice and Development party (AKP) and Turkey’s Nationalist Movement party (MHP) have joined forces to fight the June 24 election, and both parties are virulently at odds with Athens over Cyprus, and other territorial disputes, and have laid claim to numerous inhabited isles in the Aegean.

Last month, Turkish warplanes flew dangerously close to a military transport helicopter carrying Tsipras over the Aegean. In another incident, Greek troops fired warning shots at a Turkish helicopter as it flew over one of those Aegean islets. And Turkish fighter jets in defiance of a gentleman’s agreement to respect religious holidays, had only hours before entered Greek airspace on Orthodox Easter Sunday. The infraction occurred over a military outpost visited earlier in the day by Panos Kammenos, Athens’ defence minister.

Another point of contention between the two Nato members is the matter of eight Turkish military officers who have sought political asylum in Greece, following the failed coup against President Erdogan in July 2016. Two Greek border officers have been detained by Turkey since March over claims that they had strayed into a prohibited military zone. Both sides are refusing to budge or work on a deal to end this particular point of contention, with Athens claiming Ankara is holding the two as “hostages” and the pair strayed across the land border in poor visibility.

Now, Greece has moved to reinforce that land border, in part to make sure more of its servicemen don’t get lost, but more realistically and importantly, to cut off the land route entirely for those refugees. Police patrols have reported an increase in refugees trying that route, with about 2,900 crossing the land border in April alone. The rise coincided with Ankara’s military campaign against the Kurdish enclave in the Afrin region of northwest Syrian, which began in January.

For now, with tensions running high across the Aegean and with Erdogan looking to consolidate his authority even more following the June 24 vote, that Turkish application to join the EU looks as if it will gather a lot more dust before the file is ever opened again.