Russian threat has returned with a vengeance

From Washington to Brussels to Berlin, a full-scale resolve is needed in the face of unacceptable behaviour

When we look back, in decades to come, at when the West woke up to the threats it faces in the 21st century, it is unlikely we will be able to identify a single decisive moment or event.

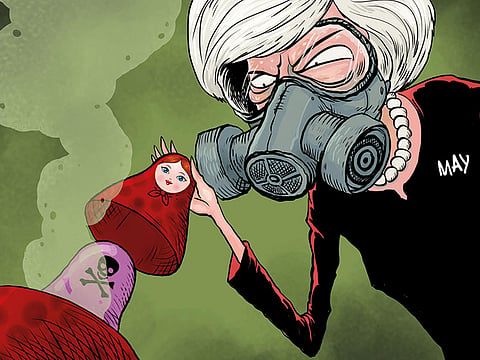

The brutal and irresponsible use of a nerve agent against former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter dominates the news today, but in years to come it will be just one sad data point in a larger emerging picture, which the murder of Alexander Litvinenko, the cyber attacks against Estonia, the invasion and annexation of Crimea, the destabilisation of Ukraine, and the development of major new military and digital weapons to attack the Western allies all help to make clear.

While small in the sweep of history, the outrage committed in Salisbury contains all the elements of the Russian regime at work — deniability, inventiveness, and an eye for the weaknesses of free and open societies. It is of a piece with the Russian soldiers who invaded Crimea not wearing their uniforms or insignia, and the massive effort to disrupt and distort the US election campaign which Moscow still breezily denies.

So, it’s not surprising that last week’s atrocity is being connected with the Russian Novichok programme identified by Theresa May.

Moscow’s success relies partly on the ease with which all facts can be contested in the “post-truth” world we have now entered, but it also takes advantage of a deep psychological weakness in the West — that we really don’t want to admit to ourselves that we face new threats, rival systems and alternative ideologies, just when we thought we were free of all that.

For military planners, this means nearly 30 years of downgrading the need for large and strong conventional forces has been a mistake. For neo-conservatives, it means the assumption that democracy will prosper even in areas where it has few foundations was hopelessly wrong. For the likes of Nigel Farage and Donald Trump, it means fawning admiration of Putin was naive. For people such as former German Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who has been happy to be paid to advance Russia’s energy interests, it means their actions were gravely ill-judged.

It is a long list. And for the general public too, it is a tiresome intrusion of reality into a world of easier distractions. We are busy getting on with our lives and, if we are arguing, it is over important but introverted issues such as health funding, tuition fees, housing or Brexit. Surely, people think, the Cold War is over?

Can it really be true that the Russians are equipping themselves to snap the undersea cables on which all our communications and finances depend? Afraid so. Are they actually positioning themselves to hack into vital national infrastructure and disrupt it? Looks like it. Can they possibly maintain Soviet levels of espionage and covert activity in our free European societies? You bet they can. Are they flying aggressive sorties to test our air defences? Yup. And surely they’re not developing new chemicals and deadly poisons as well? Of course they are.

Russia has become a rival system to our own, one of authoritarian capitalism in which an enterprise economy functions. China, deciding as it did last Sunday that Xi Jinping can be president without time limit, is evolving a totalitarian version, with adherence to party ideology and the thinking of a single man alongside what is meant to be a market economy.

Our relations with China are much better than with Russia, and rightly so. China will kidnap a dissident in Hong Kong, but not murder one in Wiltshire. The challenge from Beijing is of a different kind, focused in recent times more on economic advantage. The scope for future cooperation is greater, and the time available to get relations right still considerable.

Yet in the elevation of one man to permanent and total power, we know that a great mistake is being made. Almost all such cases throughout history turn out badly for the individual concerned, who becomes consumed by power, for the nation in question, since new thinking by others becomes stifled, and therefore for the world in general, which has to deal with the consequences. It will have little immediate effect upon anyone in the Western democracies, but it is an unambiguously unwelcome development for the future.

The slumbering West will have to wake up. If we allow a totalitarian society to jump ahead of us in new technology by the middle of the century, our way of life will be in deep trouble. And, more immediately, if we permit an authoritarian system in Europe itself to treat nations and free people as it wishes, we will see the rapid undermining of our freedom to determine our own future.

It is time for apologists to recant, optimists to become realists, and pacifists to slink away. Whatever measures Britain takes against Russia, what will really count is a realisation, from Washington to Brussels to Berlin, that a full scale strategy of the West is needed to show strength and resolve in the face of unacceptable behaviour.

That won’t happen this week. Deadly nerve agent in a Salisbury pub will not tip the balance on its own, even though the PM’s strong statement in the Commons on Monday was fully justified. It will contribute in a small way to opening the eyes of more people, even of some who do not wish to see.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2018

William Hague is a former British foreign secretary.