WikiLeaks reveals few secrets

Documents released just reaffirm what are well-known Saudi policies throughout the Arab world

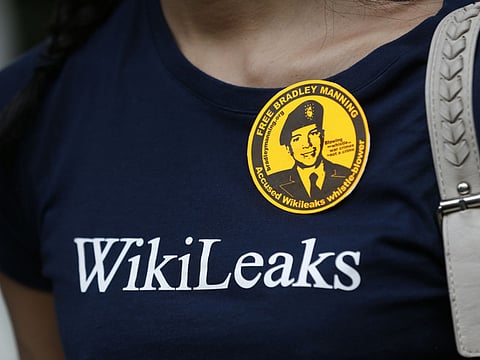

Few read the 60,000 diplomatic cables, or applied sophisticated algorithms to find out what the latest WikiLeaks revelations published last Friday unearthed, from the vaults of the Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Julian Assange, the Australian native who marked his third anniversary on Friday in Ecuador’s London embassy to avoid extradition to Sweden over alleged sex crimes, claimed that he and his team planned to release nearly half a million more Saudi items in the coming weeks in cooperation with Al Akhbar, a pro-Hezbollah Lebanese daily with a particularly checkered record against the kingdom.

Beyond embarrassment, what will the impact of these revelations be, and will Riyadh manage to minimise their consequences, just like Washington did in 2010 when WikiLeaks dumped a few million United States diplomatic cables over the internet? There are those who believe that communications between the Saudi foreign ministry and other countries as well as confidential reports from Saudi ministries to various legations will matter much more that those that mortified the US government. Others do not expect the leaks to have more than a limited political effect, persuaded that Riyadh is presumably sophisticated enough to manage such disclosures.

Critics of the kingdom are, of course, delighted to have new material to conduct their business. Moreover, these releases provide them with fresh ammunition to accuse pro-Saudi media sources that minimise the importance of the cables, even if, and based on what was revealed to date, most of what Al Akhbar concentrated on — Lebanese officials seeking and receiving financial support from Saudi Arabia — is well known. While titillating details focused, for example, on Samir Geagea, the leader of the Lebanese Forces and presumed March 14 presidential candidate, after he sought and received cash to relieve his party’s financial problems, the overwhelming majority of Lebanese politicians were on any number of payrolls, ranging from Iran to Saudi Arabia and including Qatar, France, and others. In fact, the frequency with which Lebanese politicians requested such disbursements are part and parcel of local legends, including the special payments made by Doha in 2008 to 128 deputies to finally elect Michel Suleiman head of state. Naturally, one could debate the merits of financial diplomacy as a legitimate way to conduct oneself, but this is neither new nor is it exclusive to Saudi Arabia.

To their credit, Saudi authorities acknowledged the authenticity of the leaked documents but warned that those who are sharing them over social media outlets should be aware that some could be fakes. Moreover, Riyadh cautioned citizens from engaging in selective interpretations since the documents — that were available as single pages even when multiple pages existed — were little more than bits of information. In other words, what the Saudi Wikileaks items lacked, much like their American counterparts, were appropriate perspectives that could confirm whether any of the contents translated into policy. It was critical to note that the kingdom is a monarchy where senior diplomats shared their views with members of the ruling family entrusted with the conduct of the country’s affairs. The monarch was the sole decision-maker, notwithstanding whatever counsel he may have received, and those who study Arab Gulf monarchies understand that rulers tap multiple sources of information before making their choices.

Highest veracity

Like their US counterparts, the Saudi WikiLeaks documents were reportages that varied in quality and depth. Some were likely of the highest veracity whereas others were of the poorest value. Some were analytically sound whereas others were probably unreliable. Most were, and this was probably as accurate as one could make it to be, marginal. To be sure, their authors hoped to guide policy, perhaps even influence the process, even if they seldom did.

The Assange team promised to post another 500,000 documents over the course of Ramadan, although it is unclear what kind of impact they will have throughout the region. Of course, Saudis and non-Saudis alike are anxious to learn what else might be included in them, especially if real scandals emerge, even if the lesson from the 2010 release of American documents illustrated how little of what really mattered were made public. The reason is quite simple: no one records real secrets anymore. What is left is a collection of reports that touch on the mundane, topped by hearsay galore.

Consistency requires one to take note of the embarrassment that these latest leaks created for Riyadh. There is no denying that. Yet, it is also true that nothing ought to surprise, given the propinquity to produce tonnes of reports. One is not sure how many statements, email communications, letters and assorted cables are produced each working day by the millions of government workers around the world but one must assume that the numbers are astounding. That fact, above all else, significantly diminishes their value. No leader worth his salt has the time to read, absorb and act upon even a tiny few.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of Iffat Al Thunayan: An Arabian Queen, London: Sussex Academic Press, 2015.