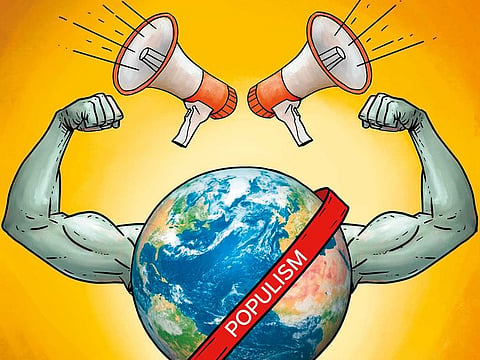

Why democracies are embracing populism

There is a common thread that runs in Trump’s rise, Brexit and Modi’s success

The morning after both Donald Trump’s victory and the Brexit referendum, when a mood of paralysing shock and grief overcame progressives and liberals on both sides of the Atlantic, the two most common refrains I heard were: “I don’t recognise my country anymore,” and “I feel like I’ve woken up in a different country.” This period of collective disorientation was promptly joined by oppositional activity, if not activism. People who had never marched before took to the streets; those who had not donated before gave; people who had not been paying attention became engaged. Many continue.

Almost three years later the Brexit party, led by Nigel Farage, is predicted to top the poll in European parliament elections in which the far right will make significant advances across the continent; Theresa May’s downfall could hand the premiership to Boris Johnson; Trump’s re-election in 2020 is a distinct possibility, with Democratic strategists this week predicting only a narrow electoral college victory against him. Elsewhere, Narendra Modi, the reactionary Hindu nationalist leader of India, enjoyed a landslide victory.

Sooner or later progressives are going to have to stop being stunned by these electoral defeats. The first time, it is plausible to ask, “How could this possibly happen?” But when that possibility recurs in relatively short order, what once presented itself as a shock has now curdled into self-deception. It turns out that the country you woke up in is the precisely the one you went to bed in. If you still don’t recognise it then you are going to have real problems changing it.

There are any number of lessons we might draw from this moment — for instance, the fact that our capacity to stage marches has outpaced our ability to build effective movements or the media’s efforts to maintain credibility. We are in a period during which facts are devalued.

Ethnic and racial plurality and migration as a lived experience are older than any nation state, but equality is a relatively new idea, and some don’t like it. People forget how recently African Americans couldn’t vote, and that Winston Churchill told his cabinet “Keep England White” was a good campaign slogan.

These electoral victories are, largely but not exclusively, the products of those age-old prejudices. Take Britain. In January 2016, 64 per cent of people from an ethnic minority said they had been targeted by a stranger. That’s before Brexit, and already terrible. That proportion rose to 76 per cent this year. Things were bad. They are getting worse. These rivers run deep — winding through empire, imperialism, caste, settlement, colonialism, white supremacy and beyond.

That’s not all these countries are. Wherever there is bigotry you will find an impressive tradition opposing it and a potential audience willing to be weaned off it. A recent survey in the US, for example, revealed that one in seven Republicans agreed with the statement: “When it comes to giving black people equal rights with whites, our country has not gone far enough”.

There is no denying that bigotry, once embedded in a political culture, is difficult to excise. But it cannot be avoided for reasons of expediency and complicity either. That is in no small part how we got here: people who knew better eschewing “difficult conversations” because it would cost them votes.

Nor can racism be met halfway, any more than you can remove half a cancer and expect it not to grow back. Attempts to triangulate with weasel words about the “legitimate concerns” of “traditional voters” are dishonest. Concerns about high class sizes and over-stretched welfare services are obviously legitimate; blaming minorities for them is obviously not. Facilitating a conflation of the two and hoping no one will notice is spineless. It also doesn’t work. In the words of the great white hope of Conservative electoral strategy, Australian Lynton Crosby: “You can’t fatten the animal on market day.” You can’t go around producing anti-immigration mugs, pathologising Muslims and demonising asylum seekers for a decade and then expect a warm a reception for open borders in the few months before a referendum. Or, if you do, the very least you can do is not keep being shocked when you lose.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Gary Younge is an acclaimed political columnist.