Turkey's recurring nightmares

An activist foreign policy creates its own troubles for the country trying to help resolve problems

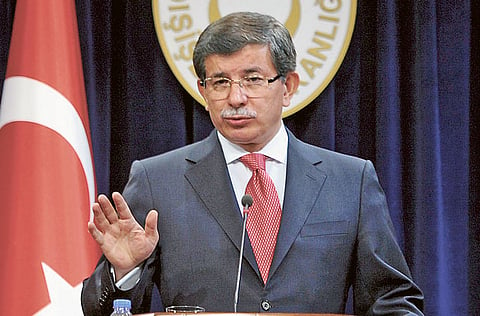

One recent night in Ankara Turkey's foreign minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, woke up drenched in sweat. "I had a nightmare about a crisis in Libya," he recalls, speaking on his way to Brussels. "The real crisis was in Syria, though, and I was unable to fall back asleep."

The bloodbath in Syria is only one headache afflicting the architect of Turkey's policy of "zero problems with the neighbours". Last week the French Senate passed a bill to make it a crime in France to deny that the mass killings of Ottoman Armenians in 1915 constituted genocide.

Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey's prime minister, had threatened retaliatory measures were the Senate to follow the lower house, which passed the measure in December. Yet no sanctions have been announced —perhaps because they are unlikely to sway Nicolas Sarkozy, France's president, who is expected to sign the bill into law.

Turkey may not care much about the fallout from this on its relationship with the European Union. The membership talks that began in 2005 have ground to a halt, not least because of Sarkozy's opposition. Continued deadlock in Cyprus is a big problem. But it is not only the Europeans who are causing trouble. Until recently Turkey was boasting not of its EU aspirations but of its shiny new alliances in the Middle East, where its secular free-market democracy is a model for some.

Visa requirements were liberalised across the region and trade has flourished. Erdogan frequently met Syria's president, Bashar Al Assad, and his wife. Turkey helped to get Al Assad off the hook for his alleged role in the 2005 assassination of former Lebanese prime minister, Rafik Hariri.

In 2008 it almost pulled off a peace deal between Syria and Israel, but the talks collapsed when Israel invaded Gaza. In 2010, when Turkey voted against tougher UN sanctions against Iran because of its nuclear programme, it was widely accused of turning its back on the West.

Now Davutoglu's secular critics have a new accusation: that he is forging a Sunni block to counter Iran's influence.

They say this explains Turkish support for Al Assad's Sunni opponents and especially for the Muslim Brotherhood. Turkey also makes no secret of its support for Iraq's Sunnis and, more recently, its Kurds.

Sectarian strife

Iraq's Prime Minister, Nouri Al Maliki, went so far as to claim that Turkey was stirring up sectarian tensions in his country. Erdogan retorted that Al Maliki was fomenting sectarian strife with his clampdown on Sunni politicians.

Davutoglu says Al Maliki's actions could unleash a sectarian war in the region. Al Maliki notes that Turkey, with its Shiite minority, might not be spared.

Soli Ozel, a commentator on foreign affairs, says the war of words with Al Maliki suggests that Turkey never had a plan for a post-America Iraq.

Erdogan's more Islamist supporters have a different gripe. Although Turkish ties with Israel remain frozen over the 2010 Mavi Marmara affair, they fret that Turkey has become America's regional stalking horse. They cite the decision to host a Nato defence-radar system, which they assert has as one goal to defend Israel from possible Iranian attack.

Davutoglu denies that the radar system is directed against Iran or Russia; yet he speaks, rather surprisingly, of a golden age in Turkey's ties with America.

He also argues that the upheaval in the Middle East cannot be entirely put at Turkey's door. Yet the inspiration that it offered to repressed Arab masses has been powerful.

As Al Assad's forces continue to slaughter innocent civilians, many in Syria and beyond are hoping that Turkey will ride to the rescue. But the Turks would do this only as part of a coalition of the willing.

With a presidential election looming, America has little interest in foreign adventures. Nato is unlikely to intervene. So what would happen if a massacre took place? Would Turkey send troops over the border? And how might Iran respond? Davutoglu has no ready answers. What is certain is that he will have many more sleepless nights.