Sudan’s changing landscape

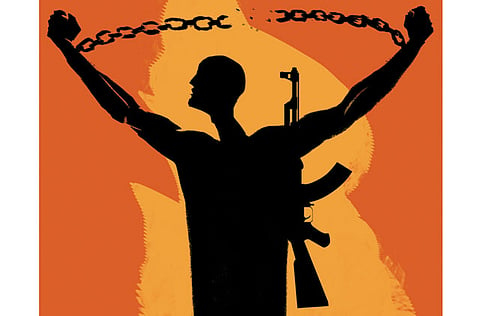

Sudanese are facing an ideological regime depending on ideological militias

A few days after the early demonstrations in October 1964, a member of Sudan’s supreme military council called Fatima Ahmad Ebrahim — a key leftist figure — to his office warning her over her role in the demonstrations. He told her: “Only being a woman saved you from jail.”

Although Sudan at that time was under a military dictatorship, the manners of the ruling elite were totally different and showed great respect for some values such as avoiding harming women by all means. For decades, police in Sudan never touched a woman even during anti-government demonstrations.

A lot has changed in Sudan in 48 years — in geography, economy, politics, culture and manners. But some of those who were in the heart of the 1964 uprising are still around. Now, there are enough signs that the protest against the regime will not stop. But those Sudanese who proved in all their history that they are masters of civil disobedience, might now face a different version of their early uprisings in October 1964 and in April 1985.

In both uprisings (October 1964 and April 1985), the army was neutral and didn’t shoot a single bullet against the protesters and took the side of the revolts, helping to overthrow the dictatorship. Both uprisings were led by a strong front of parties and unions. The transition of power was so smooth through elections in 1964 and Sudan had its elected government headed by young Oxford graduate Al Saddiq Al Mahdi and again after 16 years in 1985. But time and efforts were wasted in political plots and the military jumped again to power in May 1969 in a coup lead by Colonel Jaafer Numairi and again in June 1989 by Omar Al Bashir.

Now for the first time in their modern history, the Sudanese are facing an ideological regime depending on ideological militias rather than the army. With such a regime, it is not a matter of using excessive force against the protesters but to set up plans which will lead only to a blood bath. Reports say that Sudanese intelligence is still divided as to the right way to repress the protests. While some officials are in favour of using the maximum scale of force over a short period of time, others — especially top security figures — prefer to exhaust the protesters and concentrate on main activists rather than spreading violence wildly among the people. It seems they have chosen the second solution until now at least.

But reports also said that the regime has a “plan b” which includes using secret militias formed from “non-Sudanese Mujahideen” to launch attacks against western embassies and diplomats and target the opposition with a campaign of terror in an attempt to convince the west that the potential successors of the regime are terrorists.

Last Wednesday, the main opposition parties signed a charter called “the democratic alternative” which determines the steps that will follow the toppling of the regime — exactly like what happened before the 1964 and 1985 uprisings except for the presence of Hassan Al Turabi and his party in the recent coalition. Al Turabi, who carries a big share of responsibility for the destruction of democracy in Sudan, joined an alliance with the communist party whose presence he objected to in an elected government in 1964. It was a plot took the country on a long crisis and paved the way for the coup of May 1969. In an 1985 uprising he was the vice-president of the ousted Numairi and later the godfather of Al Bashir’s coup in June 1989. Until last Wednesday, the leader of the UMA party Al Saddiq Al Mahdi was part of Al Bashir’s cabinet along with both wings of the Al Itthadi party. Only one person has remained in the same position from 1964 until now — the young leftist lawyer in 1964, Farouq Abu Esa, who announced the call for civil disobedience and who now heads the opposition coalition front called the National Consensus forces.

Times have changed. This is not the Sudan of the 1960s or 1980s, and if the regime is going to fall, many think that the uprising of a new generation will sweep the old traditional leaders as well, especially those who manipulated the political scene for decades and burdened the responsibility of the dramatic faith of Sudan.

Fatima, the veteran leftist fighter was a member of parliament, but women in Sudan do not have any dignity at present. They are among thousands of detainees and face the brutality of police once they march in the streets. A change in manners makes all those who witnessed old Sudan recall the question of the great Sudanese novelist, Al Tayyeb Saleh, when he wondered a few months after Al Bashir’s coup in June 1989:”From where this people came?”

Mohammad Fadhel is a Bahraini writer and media consultant based in Dubai

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox