Search for moral authority

This is a strange period in the history of Arab culture and politics

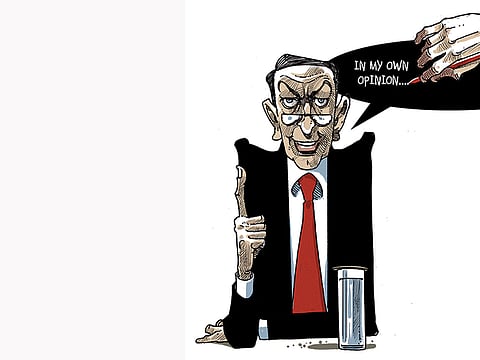

Has the Arab intellectual been reduced to a bubblehead on some agenda-driven television channel saying exactly what is expected of him or her to say?

The number of published Arab authors and higher education degree holders must have grown exponentially in recent years as a result of the proliferation of well-funded universities throughout the Middle East, but the absence of originality in the realm of ideas is still endemic. It cannot be that Arabs have collectively decided all at once to disown creativity; they are surely denied the needed platform required to break away from the sanctioned official narrative, the status quo of what is accepted and what is spurned.

But since when do ideas need a licence? It is rarely suggested that the intellectual is not a passive entity, radical if needed, but always inquisitive and courageous. “His most important activity is action. Inaction is cowardice,” wrote Alan Lightman, summarising the view offered by Ralph Waldo Emerson some 150 years ago. The late professor Edward Said’s intellectual notions, however, were particularity dauntless as they were guided by the mission of advancing the cause of freedom and knowledge. He stood at a precarious divide where he was still a part of society, thus engaged and relevant. Yet, at the same time, he was outside it, preserving the right to be critical and sceptical. Some misinterpreted this as a sign of detachment and alienation, but that was far from the truth because a fine balance is actually required for an intellectual to serve his or her intended role: “Intellectual representations are the activity itself, dependent on a kind of consciousness that is sceptical, engaged, unremittingly devoted to rational investigation and moral judgement; and this puts the individual on record and on the line,” he wrote.

Such moral authorities are lacking these days, but this has not always been the case.

Whenever a new poem by Mahmoud Darwish was published in Al Quds newspaper, I rushed over to Abu Aymen’s newsstand that was located in the Nuseriat refugee camp’s main square. It was a crowded and dusty place where grimy taxis waited for passengers, surrounded by fish and vegetable vendors. Darwish’s poetry was too cryptic for us teenagers at a refugee camp in Gaza to fathom. But we laboured away anyway. Every word and all the imagery and symbolism were analysed and decoded to mean perhaps something entirely different from what the famed Palestinian Arab poet had intended.

We were a rebellious generation hungry for freedom that was soon to carry the burden of the popular uprising, or Intifada, and we sought in Darwish’s incomparable verses, not an escape, but a roadmap for revolution.

Darwish represented a generation of revolutionary intellectuals: Humanists, Arab nationalists, anti-authoritarian and anti-imperialists.

Back then, ideas seemed to be more like a mosaic, involved and intricate productions that were enunciated in such a way as to produce works that would last a generation or more.

A novel by Abdul Rahman Munif represented the pain of a past generation and the aspiration of many to come. Language was timeless then. One would read what Tunisia’s Abu Al Qasim Al Shabbi wrote in the 1930s and Palestine’s Samih Al Qasim much later and still feel that the words echoed the same sentiment, anger, hope, pride, but hardly despair.

The “Arab Spring” resurrected the words of Al Shabbi, but also those of others. But this hardly concerns the “spring” per se, but instead the Arab intellectual and what he/she represents or fails to represent.

When I was younger, and Said was still alive, I always wondered what his impressions of certain events were. His non-conformist political style — let alone his literary genius — did more than convey information and offer sound analyses. It also offered guidance and moral direction. After he promised me an interview, he wrote a short email about having to undergo ‘very painful’ chemotherapy and asked to postpone. I never heard from him after that. He passed away. I had way too many questions that until this day remain unanswered.

Professor Said, and many such giants, are missed most during this current upheaval, where intellectuals seem negligible, if at all relevant. There is no disrespect intended here, for this is not about the actual skill of articulation, but alternatively it concerns the depth of that expression, the identity and credibility of the intellectual, his very definition of self and relationship with those in power.

Sure, there were those scholarly minds who joined Egyptian youth as they took to the streets in 2011, but did so timidly. Some appeared to be members of a bygone generation, desperate for validation. Others were simply present, without owning the moment or knowing how to truly define it or define their relationship to it.

Yet, the “spring” generation, which prided itself on being “leaderless”, proved equally incapable of capturing popular imagination beyond the initial phase of the protests, nor offered a new cadre of intellectuals that would formulate a new generational vision. Many of the secularist intellectuals, who had already grown distanced from the masses, in whose name they had supposedly spoken but never truly represented, were confounded by the new reality. Although they failed to bring about any kind of change, they feared losing their position as the hypothetical antithesis to the existing regimes. Their words hardly registered with the rising new generation. They were out of touch and as surprised as the regime by the changing tide.

This is a strange period in the history of Arab culture and politics. It is strange because popular revolutions are propelled by the articulation and insight of intellectuals. It is truly unparalleled since the Al Nahda years (roughly between 1850 and 1914), which witnessed the rise of a political, cultural and literary movement in Syria, Egypt and elsewhere with the utilitarian blend between pan-Arabism and pan-Islamism. The intellectuals of that Arab, Islamic renaissance seemed often united in their overall objectives, as they stood against Ottoman dominance and imperialist ambitions. They were inclusivists in the sense that they sought answers in European modernity, but self-respecting enough to challenge foreign dominance through the revival of Arab culture and Islamic teachings.

How that movement evolved is quite interesting and complex. Today’s Muslim reformists — the so-called moderates — can be traced back to those early years. Mohammad Abduh and Jamal Al Deen Al Afgani are towering figures in that early movement, although they were and remain controversial in the eyes of the more conservative Islamists. The secularists, on the other hand, merged into various schools and ideologies, oscillating between socialism, Arab nationalism and other brands. Much of their early teachings were misrepresented by various dictatorships that ruled, oppressed and brutalised in the name of Arab nationalism.

Still, there were prominent schools of thought, manned by formidable intellectuals, whose ideas mattered greatly. There seems to be no equivalent of yesteryear’s intellectual in today’s intellectual landscape. The closest would be propagators of ‘moderate Islam’, but they are still a distance away from offering the kind of coherence that comes from experience, not just theory. The secularists have splintered and become localised, jockeying for relevance and vanishing prestige.

History without the moral leadership of intellectuals is devoid of meaning, chaotic and unpredictable. But this is a period of seismic historical transition and it must eventually yield the kind of intellectual who will break free from the confines of the ego, regimes, self-serving politics, sects, ideologies and geography.

Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist, a media consultant, an author of several books and the founder of PalestineChronicle.com. He is currently completing his PhD studies at the University of Exeter. His latest book is My Father Was a Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (Pluto Press, London).