There was a time, for about three years, during my last years in university and beyond, when I liked to go caving. There was a great sense of adventure and, admittedly, back then, my Body Mass Index was a lot lower and I could fit through tight spaces.

Weekends away caving were spent under The Burren of County Clare in western Ireland, where the cave systems were deep and went on for several kilometres each. The golden rule going down was to let people know when you expected to return — and check the weather beforehand. Any rain quickly funnelled into the cave system, turning caverns into cisterns, and you could be stuck waiting it out for the water levels to fall.

Here’s the thing about being underground for up to six hours at a time — the temperature always remained constant there, around 6 degrees Celsius — and before you got even the first glimpse of light that would cut through the black damp inky darkness, you could smell fresh air coming in first. Then you’d see the light.

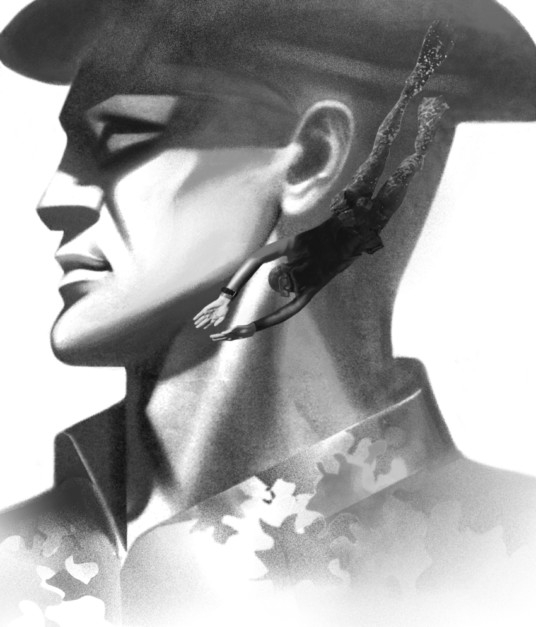

They were good times, and I have been reminded of those over this past week, watching with great interest the incredible rescue mission that was successfully undertaken by the local government in northern Thailand, Thai Seal Teams and a range of international cave divers and special medical personnel who worked tirelessly around the clock, in extremely difficult conditions, to ultimately rescue the 12 Wild Boar football players and their coach who were lost and trapped five kilometres in a cave system in the remote north of their country.

These are times when good news is often at a rare premium, where we are used to tragedy and almost immune, as it were, to the suffering endured by so many is so many places. Yet, for once, over the course of three days, we all felt compelled to listen to every update, how first four, then four more, then the last four and their coach were saved from their dark and dank dungeon.

Imagine, if you will, what it would be like not to eat one morsel of food for a day, and the only water you drink would taste muddy and gritty, leaving you sick. Now multiple that by 14 days, and you begin to get a sense of the physical nightmare these Wild Boards endured.

But then there’s the darkness.

Unless you’ve experienced such blackness, there are few who would describe to you what the absolute absence of light looks and indeed feels like. Nothing. It’s a blindness of the seeing, the blackness of the darkest soul, the complete absence of everything. You see nothing. You are blind to what’s right before your eyes.

And then imagine how that plays on your mind.

It is a frightful place at best. But knowing that there’s no food, no light, no way out, and no end to the tricks that your mind can play on you, makes it unbearable.

Now imagine being 12 years of age when that is happening to you, where your friends are also scared, and there’s but one adult to keep your spirits up — and he is enduring this psychological darkness too, except worse, for he must try and keep your spirits up too.

The boys were found after ten days by a specialist team of Australian cave divers, huddled on a mud-strewn redoubt. That in itself marked a day of miracles, where there was at least a glimmer of hope that they might indeed be somehow saved for their darkest hour.

Cave diving is a risky adventure.

I stand fully in awe then of the Australian and British cave divers who risked everything to search the cave complex in the first instance. They are more used to being called in to retrieve bodies, doing dirty work in dark places where no one else will dare tread water. An army of personnel got to work, putting hundreds of pumps to work to lower water levels. What was worrying was that the seasonal rains would indeed come at any time, making all of those pumps obsolete and threatening the very redoubt that those boys and coach clung too.

I have learnt more this past week about oxygen levels in the normal atmosphere, and that the very huge number of Thai SEALS and others working together to save the Wild Boars were using up precious oxygen in the chambers sealed off from the outside world because of the high waters.

And then came word that one of the Thai SEALS, Saman Kunan, perished in the Tham Luang caves while laying a network of oxygen tanks that were needed by the rescuers and those to be rescued. He is a man who deserves the highest honours that Thailand — or others — can bestow, giving up his life in the service of mankind without a care for his personal safety other than to accomplish the mission of saving those Wild Boars. Bless him, and his family.

There are news stories that often vexate and irritate — and we are all too used to those.

Someone once asked my why isn’t there a newspaper that only tells good news, that newspapers like telling bad news.

The truth is that there is so much bad news, that good news is hard to come by.

This past week we have had good news; great news; news that lifts the heart; news that reminds us that if we can indeed work together, if faced with a task that seems impossible, we can indeed work to perform miracles.

The bad is news is that we don’t.

And just like in Tham Luang cave, we choose to see darkness. We see nothing. We are blind to what’s right before our very eyes.