Pakistanis want the plain truth

Nasim Zehra writes: Judicial commission, not a parliamentary panel, will get to the bottom of the Abbottabad fiasco

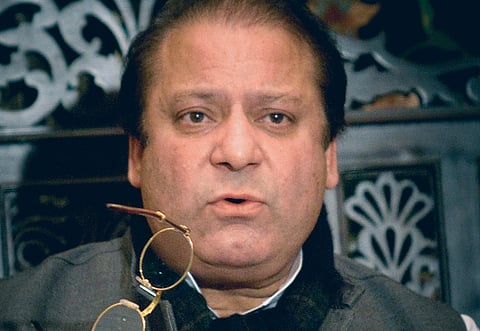

The Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N), fortunes in recent months — marked by reactive, angry and dull politics and confronted by Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari’s incredible political cunning — have been on a downward trajectory. However, in the post-Abbottabad operation period, party chief Nawaz Sharif has responded to the national challenge in a statesman-like fashion.

Of three options to conduct a national inquiry into the fiasco, Sharif opted for the third and sought its execution within a realistic time frame. Let’s examine all three options:

Option one is the existing inquiry commission headed by the adjutant-general as announced by the Pakistani army and endorsed by Prime Minister Yousuf Raza Gilani in his May 9 parliament speech.

But such an inquiry, whose primary task would be to conduct an investigation into the intelligence and security failures, will have little credibility if the head of the inquiry belongs to the very institution whose performance is in question.

Option two could have been a parliamentary commission with representatives from all elected parties. Perhaps the existing bipartisan Parliamentary Committee on National Security could have been tasked to conduct the inquiry into the Abbottabad operation.

While such an option would have been in the spirit of parliamentary politics, in all likelihood there would be no substantive outcome because most parliamentary parties do not appear to be in the mood to seriously examine Pakistan’s own failures in the fiasco.

The statements made by political leaders across the board show they are all satisfied waxing eloquent about violation of Pakistani sovereignty with some opposition leaders calling for the president’s and the prime minister’s resignation.

The government itself has decided to adopt a hands-off approach on the internal dimension of the Abbottabad operation. Gilani’s May 9 speech was a hotchpotch of historical recall about Osama Bin Laden’s evolution, some contradictory statements about the US role and finally a desperate effort to convince the Pakistani army that there would be no accountability initiated by the civilian government.

Eyewash

In fact, in what will go down as one of the worst speeches of his political career, Gilani announced that the army’s response to the Abbottabad operation was “adequate” and that while there was complete unity among all national institutions, the media was playing a divisive and negative role!

Maybe in his ‘all-praise for the security establishment’ mode, Gilani overlooked the fact that the army itself had acknowledged in an ISPR press release that there had been a security and intelligence lapse.

Equally interesting was the fact that instead of standing by the elected prime minister and being present in parliament when he was making an important speech concerning the army, the army chief was visiting garrisons and complaining about lack of information made available to the media and hence to the public.

Accountability

The army chief has been doing the garrison rounds to deal with restive troops who are raising questions regarding the Abbottabad fiasco. But Gilani, perhaps tutored by the Foreign Office and the GHQ officials, would have Pakistanis believe that essentially all is well on the internal front. That there is no need for accountability.

Essentially operating in the same vein, it seems that most parties represented in the Parliamentary Committee on National Security, did not deem it necessary to call for the setting up of an independent inquiry commission to investigate the Abbottabad fiasco.

Not a word on May 9 from the Raza Rabbani, committee chairman, on setting up an inquiry commission when he addressed the media after the committee’s meeting.

Against this backdrop where parliamentarians, either because they know how the army has sent packing civilian prime ministers who have even talked of holding independent inquiries on military–related fiascos (Mohammad Khan Junejo and Sharif over Ojhri Camp and Kargil respectively) or perhaps playing power politics by seeking GHQ support, are in no mood to hold the security establishment accountable.

Opting for a parliamentary committee would have been a less than wise option. It would have become a casualty of political point-scoring by the politicians.

Option three is invoking the Inquiry and Commission Act of 1956 and set up a judicial commission to hold an inquiry. The commission, headed by the Chief Justice of Pakistan with high court chief justices as its members, with the authority to question any office holder or official from any institution, is likely to present a more credible report to the government and to the people of Pakistan.

The judicial commission can also call independent security and intelligence experts to enhance its capacity and credibility while conducting the inquiry.

The judicial commission’s report must be made public and the elected government should implement its recommendations.

Perhaps the only criticism of establishing a judicial commission would be that the judiciary is yet again being encouraged to play an expanded role, and this time at the cost of parliament’s role.

In principle this maybe correct, but not in substance. In substance, a parliamentary committee would play politics instead of conducting a fair inquiry while the judiciary and especially the Chief Justice, beholden partially to General Ashfaq Kayani for his restoration, would be constrained to opt for fair play. The commission would be in sharp public focus compelling it to competently implement its mandate.

Such a judicial commission set up by the government would obviously not amount to judicial activism but would indeed be viewed as the judiciary performing its constitutional role.

The ball is now in Gilani’s0 court. In his May 9 speech he had undertaken to consider any proposals made by the opposition to deal with the post-Abbottabad crisis. With the objective of identifying and fixing Pakistan’s own internal institutional and policy-making weaknesses, Sharif’s proposal for a judicial commission is worth adopting.

Nasim Zehra is a writer on security issues.