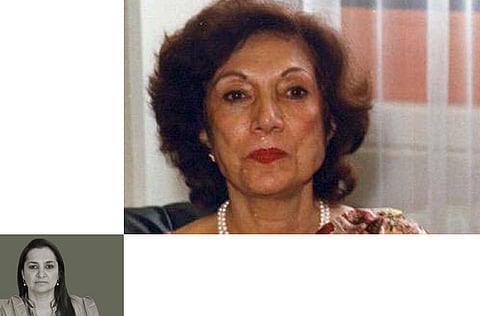

Nusrat Bhutto's enduring legacy

The former first lady must be given her due place in Pakistan's quest for democracy

Begum Nusrat Bhutto’s death has forced us all to re-focus on the almost forgotten icon of Pakistan’s democracy. As the Bhuttos, especially Sanam, Fatima Bhutto, Bilawal, Bakhtawar and Aseefa and the rest deal with the pain of both Begum Nusrat Bhutto’s death and tragic life, inevitably, family bickering, power struggle and politicking will also accompany Begum Bhutto’s last rites. But there is a larger canvas that deserves recall.

Prolonged illness had caused both Begum Nusrat Bhutto’s fading away and her unsung departure from Pakistan’s public space. Equally, the woman who bravely led the resistance against Pakistan’s most toxic dictatorship, this former first lady, the head of the Pakistan People’s Party’s (PPP) women’s wing and subsequently the party’s chairperson and also a senior minister, has largely been absent from Pakistan’s political narrative. Among the few known written accounts of Begum Bhutto’s role in Pakistan’s democratic politics are the ones written by the widely respected Bashir Riaz, now a chronicler of the Bhutto politics.

The news of her death in Dubai has jolted us all into vividly recalling Begum Bhutto’s determined acts of bravery and defiance against dictatorship while also recognising the fact that post-Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, it was this iconic figure who carved out the path of resistance and party’s survival and subsequently of a collective democratic struggle in the shape of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD), that her equally brave daughter followed.

Until repeated tragedy broke her and she went into exile with her daughter, Begum Bhutto remained active on the domestic and international scene. In June 1993, when she led, on then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s invitation, Pakistan’s delegation to the World Human Rights’ Conference to Vienna, Begum Bhutto held her own with dignified ferocity. As delegates, some of us witnessed her taking up the case of the Kashmiris with great conviction. In fact, she strongly chided the Foreign Office team for “trying to water down” her own text of the speech condemning Indian atrocities in the valley. From the podium, in a hall full of delegates, Begum Bhutto, shouted down the Indian delegates, who sought a right of reply to her very hard hitting speech. And when the Indian press raced towards her as she walked off away from the podium and asked her question about Pakistan’s politics , she hit back saying “Do not try and divide us, here for the Kashmir cause we are all one.”

Begum Bhutto confronted the malevolence of the Pakistani state, including sections of the country’s judiciary, in the shape of a her husband’s removal, his arrest, his trial, her family’s displacement and exile, her husband’s judicial murder, his hanging and his burial in the darkness of the night. She bore the brunt of repeated pain and finally after the violent deaths of her two young sons and subsequent intra-family pressures, Alzheimer’s pulled away Begum Bhutto from public life. Burdened with these unbearable tragedies, fate intervened with this memory-losing illness, as if to ease her pain.

Begum Bhutto endured pain of oceanic proportions and in her death. One is tempted to ask why she needed to endure so much more than her fair share. But we need to be equally mindful that many acts of the Pakistani state have been no less callous. Begum Bhutto and many others rose to the challenge, were tall figures, have left us and our children a legacy of resistance and struggle that we will always be proud of, even if deeply pained. But we must always remember some of these havoc-wreaking acts of the state not only destroyed individuals but also contributed to the hijacking of the Pakistani potential and for bright future.

For Pakistan, the costs of dictatorship have been devastating. While many commentators on Pakistan talk of the economic benefits of stable dictatorships, how do we ignore the mounting and de-stablising costs of the long shadows of military dictatorships? Dictatorship derailed the only accountable system of governance known to human civilisation. Also, these dictatorships have contributed to the creation of tales of conspiracy, of victim-hood, of divisiveness and of hate.

We have to retrieve ourselves. The only way is a democratic system, that holds us accountable. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was pulled up by political forces, he even arrived at an agreement with the Opposition. But Zia’s ambitions and the army’s misguided nationalism, empowered by a vindictive capitalist class which saw itself wronged by Bhutto, drove us away from what would have been a semblance of a functioning national management system.

One of the legacies of dark dictatorships have been how we have lost the moments, lost our stars in their prime and are left to lament them. Here is the irony — while the state contributed to what was unparrelleled suffering in the annals of Pakistan’s history, now in death we are extolling her, reporting her, analysing her, bereaving her. Other great men like Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Dr Abdus Salaam were banished from Pakistan in their prime, we eulogised after they died.

That’s what our past power politics has done to us. It’s been a weave of compromises, patch-work of contradictions drained of any public morality. But that is what early military interventions made politicians do. In her time, Begum Nusrat Bhutto came out to wage a genuine resistance struggle. What happened subsequently we all know. Zia led the charge of the abiding power brokers and crassly injected low-level maniuplation tools to intimidate and break the PPP. Politicians then learnt to respond and also tragically ape the abiding power brokers.

Rising above all other divides, the woman to whom the credit for laying down the foundations of Pakistan’s most difficult and yet the most principled struggle against dictatorship, must be given her due place in Pakistan’s democratic history.

This is how a nation’s story, a nation’s narrative and soul are nurtured. She is one reason why Pakistanis, in the context of democratic struggles, must feel ten feet tall. But as for the yield of today’s democracy, it is largely an indictment against the current politician.

Nasim Zehra is a writer on security issues.