My stutter made me a better writer. Here is how

Stuttering is a violent incantation that can break open normal conversation

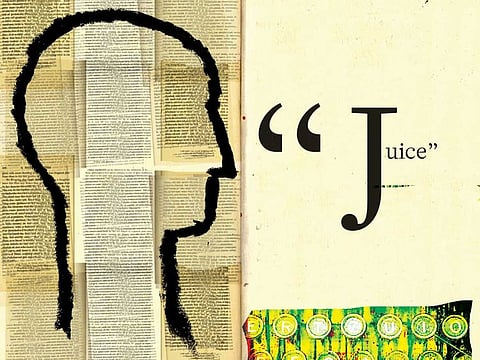

The J in “juice” was the first letter-sound, according to my mother, that I repeated in staccato, going off like a skipping record. This was when I was 3, before my stutter was stigmatised as shameful. In those earliest years my relationship to language was uncomplicated: I assumed my voice was more like a bird’s or a squirrel’s than my playmates’. This seemed exciting. I imagined, unlike fluent children, I might be able to converse with wild creatures, I’d learn their secrets, tell them mine and forge friendships based on interspecies intimacy.

School put an end to this fantasy. Throughout elementary school I stuttered every time a teacher called on me and whenever I was asked to read out loud. In the third grade the humiliation of being forced to read a few paragraphs about stewardesses in the ‘Weekly Reader’ still burns. The ST is hard for stutters. What would have taken a fluent child five minutes took me an excruciating 25.

It was around this time that I started separating the alphabet into good letters, V as well as M, and bad letters, S, F and T, plus the terrible vowel sounds, open and mysterious and nearly impossible to wrangle. Each letter had a degree of difficulty that changed depending upon its position in the sentence. Much later when I read that Nabokov as a child assigned colours to letters, it made sense to me that the hard G looked like “vulcanised rubber” and the R, “a sooty rag being ripped.” My beloved V, in the Nabokovian system, was a jewel-like “rose quartz”.

My mother knowing that kids ridiculed me — she once found a book, ‘The Stuttering Parrot’, that had been tossed onto our lawn — wanted to eradicate my speech impediment. She encouraged me to practice the strategies taught to me by a string of therapists, bouncing off an easy sound to a harder one and unclenching my throat, trying to slide out of a stammer. When I was 13 she got me a scholarship to a famous speech therapy program at a college near our house in Virginia.

Speech therapy

For three weeks that summer I sat in a small room at a table with a voice monitor, a black metal box with a light that would turn from green to red if I made a hard onset, forcing air out of my mouth too quickly. In front of me was a thick workbook, filled with pages of single letters, letter groups and words. I said each a hundred times using the programme’s method of not pushing air out, but gently moving into each initial sound. If the light turned red, I had to start all over. After days filled with hours of repetition (lob-ster — lob-ster — lob-ster — lob-ster) my mind unfocused and I floated up, watching the skinny, pathetic girl in the sundress and tyre-tread sandals trying so desperately to find a little grace.

Flash forward 25 years. After a plethora of speech therapy, my stutter was less disruptive; I moved through the world trying to pass as a fluent person, one unmarred by disability. Whenever I stuttered, I disassociated: That struggling human was not me. This strategy mostly worked until one night I found myself at a party in Brooklyn surrounded by people freely and flamboyantly stuttering. I discovered that the party host was the editor of a stuttering newsletter and that many of the partygoers were members of the local chapter of the Stuttering Association of America. When I mentioned that I attended the speech programme in Virginia, our host told me that the program’s therapies are considered invasive, even cruel. Nowadays stutterers get therapy to stutter more comfortably, not to obliterate their stutter.

I realised as I listened to one after another tell their stories that they were not impressed with my fluency. No. They felt sorry for me. Having tamped down my speech, I will never really know who I am.

This paradigm shift blew my mind. It had never occurred to me to tell myself the way I spoke was OK, it’s the fluent world that needed to practice acceptance. When I watched “The King’s Speech,” a film about King George IV’s stutter, I didn’t buy the triumphant ending, when, with the help of his speech therapist Lionel Logue, the king delivers with fluency his announcement that Britain will enter Second World War. The actual meaning and glory in the film, I realised, occurs between the king and Logue inside their sessions. The king exposes his vulnerability and Logue reacts not with judgement or disgust but compassion. For the first time the king is seen.

Finally I get it: Stuttering is a violent incantation that can break open normal conversation. What happens in that breach is up to the stutterer and her listener.

Audiobook

I was reminded of this not long ago, as I sat inside a sound booth in front of a microphone just as huge and intimidating as any in ‘The King’s Speech’, preparing to record the audio edition for my forthcoming book ‘Flash Count Diary’. I was anxious. Because of my stutter, I wasn’t sure that I could. Conversing, teaching, even reading out loud were all part of everyday discourse, but recording an audiobook would take me into the world of professional oratory — a world, I assumed, from which I’d always be excluded.

As I started to read, I remembered again my complete defencelessness before the incomprehensible force of language. I had no control over my vocal cords, adrift on waves of unpredictable sound. This loss of control was scary but also thrilling, even ecstatic. Time after time I hesitated or stuttered and had to start over, going back to the top of the sentence. The young sound engineer was patient. His voice in my earphones was gentle and his expression open and empathetic. Afterward we talked frankly. I explained that in the classroom as I teach and at my readings, my stutter brought intimacy to my listeners. He nodded. “They can hear your vulnerability.” We agreed that while it might take twice as long for me to record my book, I could do it. Also in the final edit, he promised to include at least some of my repetitions and silences.

The central irony of my life remains that my stutter, which at times caused so much suffering, is also responsible for my obsession with language. Without it I would not have been driven to write, to create rhythmic sentences easier to speak and to read. A fascination with words thrust me into a vocation that has kept me aflame with a desire to communicate. As a little girl, I hoped my stutter would let me into the secret world of animals. As an adult, given a kind listener, I am privy to something just as elusive: a direct pathway to the human heart.

Darcey Steinke is an American author and educator. She has written five novels.