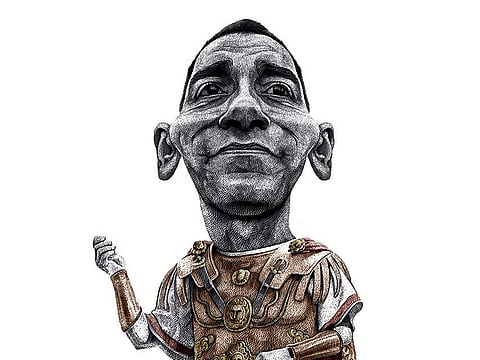

Luigi Di Maio: Rome wasn’t built in a day

Italy’s 5 Star Movement is now biggest party after last week’s general election — but its leader has a Herculean task a tough task if it is to govern

What do you get if you put 23 political parties together, keep changing the election rules, and add it a little dash of corruption?

The answer is 62 separate Italian governments since 1946 — and only the last two administrations going back almost a decade have managed to complete their full terms. Consider too the first one of those, from 2008 to 2013, had Silvio Berlusconi at the helm. It became consumed by his bunga bunga parties, fraudulent tax activities and taking Italy to the brink of needing a bailout from the international troika of the European Union, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In last Sunday’s general election, the tanned 81-year-old media mogul lost some of his formidable charisma and standing, earning a shade under 14 per cent of the popular vote. When aligned with the League and the Brothers of Italy, the centre-right political bloc still comes well short of winning enough support in both houses — a requirement under the Italian constitution — to be able to form a government.

Then there’s the 5 Star Movement (M5S)— and enter Luigi Di Maio, its 31-year charismatic leader who took the populist protest party to 32.22 per cent support — the largest in the new pizza parliament.

Under that same Italian constitution, if no grouping can form a coalition deal, it’s up to the President of Italy, Sergio Mattarella, to decide who should be given a chance to govern. And Di Maio, a university dropout and a former waiter, could very well become the next Prime Minister of Italy.

M5S presents something of a conundrum to most — it has already said that it will not enter into a coalition deal with any other political party — though it is now up to Di Maio on just how to follow through on his bold decision before Sunday’s election to name his potential cabinet. In what was then described as an “act of transparency” Di Maio included an economist, a doctor, a criminologist and an Olympic gold medallist in his cabinet in waiting. He also dismissed rivals who ridiculed his cabinet, observing that M5S would “be the ones laughing on Monday when Italians will probably take us to 40 per cent”. Not quite, but still it was a remarkable result for a protest movement founded by comedian Beppe Grillo and which has only been led by Di Maio since late last year.

Grillo, 69, is a biting satirical comedian who was a regular fixture on Italian television in the 1980s — on the same channels owned by Berlusconi — only to be sacked in 1987 for a wisecrack that suggested the then prime minister, Bettino Craxi, had his fingers in the nation’s wallet. Although Craxi was a Socialist, he was supported by Berlusconi. As it later turned out, Craxi was indeed indicted and convicted of corruption — which partially explains Grillo’s disdain for the established political order.

Grillo set up M5S in 2009 to give action to his anti-establishment claims, and it has grown steadily since then, as Sunday’s vote attests.

Grillo can’t stand for the M5S in an election: He has a conviction for manslaughter from a 1981 incident when a vehicle he was driving crashed, killing his three passengers, and his party has a prohibition on convicted criminals running for office.

Anti-establishment

M5S, which bases much of its appeal on fighting corruption, emerged as a major force in 2013 general elections and went on to win mayoral seats in Rome and Turin last year. The party too is firmly anti-establishment, anti-European Union, anti-euro and anti-consumerist — which together would make for an interesting agenda to govern should President Matarella put a call into Di Maio.

He’s from a fairly affluent family in Avellino. His father Antonio owned and ran a small construction company while his mother, Paola, taught Latin in a local school. Antonio also dabbled a bit in the now defunct Italian Social Movement — a neo-fascist party founded in 1946 by supporters of dictator Benito Mussolini, who had been captured and summarily executed by Italian Communists the previous April.

Di Maio is the eldest of three children, and studied computer engineering at Naples University. He later switched to law, never completed the degree and dropped out before making ends meet as a waiter.

His curriculum vitae also says he founded his own web and social media marketing business while studying and he worked on various video projects.

The telegenic youngster had gone up against six totally unknown candidates and a low-profile senator in an electronic vote for the M5S leadership in November that had both amused and irked traditional parties and the country’s mainstream media.

“The pathetic primary with Di Maio as a lone candidate is not only a symptom of a lack of democracy” within M5S, wrote Il Fatto Quotidiano daily, which is usually the most sympathetic to the movement. “It is also proof of the eternal immaturity, incompetence, inexperience and thrown-together nature of a movement that is getting bigger but not growing up,” the paper said.

Now, perhaps Di Maio faces his greatest marketing challenge in getting M5S to change its tone on key issues since winning the leadership election.

The party had consistently called for Italy to leave the EU and the euro, but Di Maio recently made more conciliatory noises about the idea of staying in the bloc. His reaction was also noted following the murder of a teenage girl, blamed on a Nigerian, and a revenge shooting that left six African refugees injured by a far-right extremist on February 4. Amid a public outcry, Di Maio stayed silent on the gun rampage and instead focused on Berlusconi for creating the “ticking social time bomb of immigration”.

“On matters like ethics and immigration,” wrote Catholic weekly Famiglia Cristiana, Di Maio ideas are “like those of a surfer riding a wave”.

But to Di Maio and his allies, everything M5S does presents a clear challenge to all that preceded their arrival on the political stage.

“The movement was born out of the failure of both parties on the left and right,” Di Maio said. “The real problem in Italy is that there are many citizens who don’t identify with these parties because they fail to defend the values and interests of different parts of the country.”

In this vein, it is not dissimilar to other anti-establishment uprisings in Europe. But the ideology of M5S is remarkably difficult to pin down. The party advocates social and environmental justice, is sceptical of big corporations and uninterested in — though not totally opposed to — Italy’s commitment to Nato. Yet it also is animated by a kind of libertarianism that is hostile to government and eager to loosen up the financial system.

“It has a rightist facade, over a leftist basement, under an anarchic roof,” explained Beppe Servergnini, an Italian journalist critical of the party, wrote recently in the New York Times.

If anything, Di Maio is a pragmatist — and will likely remember his mother’s Latin lessons that even when victorious Roman Empire generals entered Rome to the adoring mob, there was a slave too who rode on the chariots whispering again and again in their ears “Momento mori” – “Remember you have to die”.

The moral? All fame is fleeting.

— With inputs from agencies