Is the Caliphate a necessity?

Believers always proved that the very concept was irrelevant, and the quest for liberty has stunned every single individual who has aspired to be a ‘caliph’

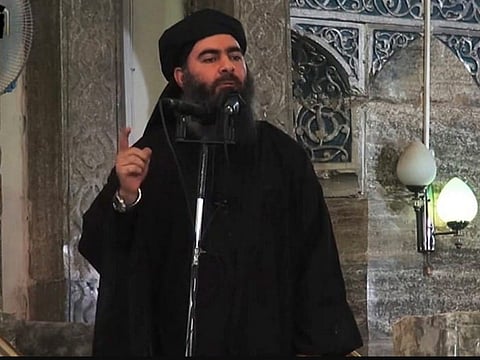

When one of the world’s most dangerous man proclaimed himself “Caliph” on July 5, 2014, at the Al Nouri Mosque in Mosul, Iraq, few stopped to ask why it was necessary to advocate a restoration of the Caliphate a century after it was abolished with the demise of the Ottoman Empire. Even fewer bothered to fully assess the quest for religious legitimacy that, apparently, only came with the Caliphate, even if most of what Ebrahim Al Baghdadi offered were antiquated thoughts. Irrespective of his whereabouts — Al Baghdadi may or may not be dead — a new chapter opened after Mosul fell, and while Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) is a spent force, a far more important question remains: Is the Caliphate necessary in the 21st century?

In an important 2008 study titled ‘The Fall and Rise of the Islamic State’, Noah Feldman — the Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard Law School — concluded that “the future of [Daesh] is very much under formation, but so is its past, which is not really over so long as its meaning is being debated and its outcome remains undetermined”. Indeed, there are those who firmly believe that the “nation-state” concept is alien to Islam and Muslims, even if it is the dominant global paradigm to manage most socio-political and economic needs. Naturally, the intellectual battle to accept or reject this concept is an old one, though its urgency in our times is evident as numerous extremist groups in dozens of societies look for salvation in the Caliphate.

Secularism is eyed with suspicion in the Muslim world not only because its vision is associated with western values, but also because there lingers a mistaken conviction that it can and does threaten Sharia, which is wholly incorrect.

No one refuted this idea better than Shaikh Ali Abd Al Raziq, an Egyptian scholar. Abd Al Raziq (1888-1966) was a renowned Egyptian judge who graduated from Al Azhar University, where he received a traditional Islamic education before he attended Oxford in the United Kingdom. In 1925, he published what still is one of the most controversial and influential books ever written, Al Islam Wa-Usul Al Hukm (Islam and the Sources of Political Authority), which argued against the very scheme of a specifically Islamic notion of government.

A firm believer, what Al Raziq aimed to do was to raise the debate on religion and its role in politics to a different level, precisely to test whether orthodoxy and reformism were compatible. His analysis placed secularism above the dogma of a theocracy, for which his peers at the Council of the Ulama — who promptly fired him — chastised the Al Azhar scholar. They simply could not accept that Sharia had no bearing on the affairs of state.

For Al Raziq, “Islam did not determine a specific regime, nor did it impose on Muslims a particular system according to the requirements of which they must be governed; rather it has allowed us absolute freedom to organise the state in accordance with the intellectual, social and economic conditions in which we are found, taking into consideration our social development and the requirements of the times”.

Equally contentious, Al Raziq affirmed that the formation of the Caliphate was based on nothing more than political necessity and not, as Ibn Khaldun advanced in his Muqadimah, on Ijma (consensus). He posited that Muslims had few choices throughout history and that they were forced to acquiesce, which produced ‘Caliphates of Tyranny’, something that numerous accounts corroborated and that Al Baghdadi highlighted during the past few years.

Al Islam Wa Usul Al Hukm was criticised by many and continues to be dismissed, though it should be venerated as a unique work of erudition. Rashid Rida called it “the latest attempt of the enemies of Islam to weaken and divide it” although he — as one of the fathers of Salafism — finally declared that Sharia cannot be codified as “State law”, which is precisely what Al Raziq deduced.

Caliphs almost always instilled themselves with the virtue of divine authority, and rejected independent political thought. They relied on force to preserve power though few fell for their stratagems. Time and again, believers proved that the very concept of a Caliphate was irrelevant, as the quest for liberty stunned every single Al Baghdadi who graced the realm.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of The Attempt to Uproot Sunni Arab Influence: A Geo-Strategic Analysis of the Western, Israeli and Iranian Quest for Domination (Sussex: 2017).