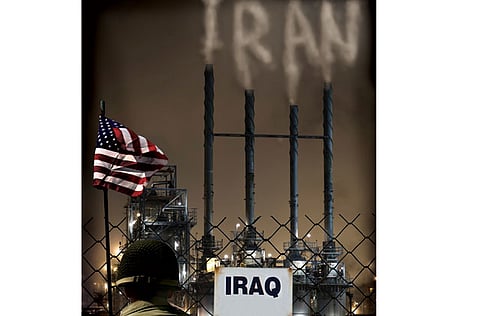

Iraq continues to frustrate US

Washington has spent $900b, lost 4,386 soldiers and caused the deaths of more than a million civilians. Now Iran is calling the shots

America has been battling for regime change in Iraq for the best part of two decades. In 1991 the US army landed in the Gulf to ‘liberate Kuwait'; in 2003 the slogan had changed to ‘liberate Iraq' but the intention remained the same to remove Saddam Hussain and the Baath party and establish instead a friendly government which would support America's own ambitions for the region and accommodate Israel.

When the Weapons of Mass Destruction justification for the 2003 invasion was discredited, the Bush administration was quick to run up the flags of democracy, transparency and human rights, promising to make a stable regional model of Iraq.

The March 7 elections, internationally monitored and supervised, were an improvement on 2005 when many Sunnis boycotted the process entirely. This time 63 per cent of the population turned out to vote with some unanticipated and unwelcome results.

Whilst America's favoured contender, secular Shiite Eyad Allawi, led his Iraqiya coalition to a narrow victory with 91 seats and a large percentage of the Sunni vote, the complicated electoral system established after much wrangling means that the next prime minister has to be chosen by a majority of the 325-member Council of Representatives.

The incumbent, Nouri Al Maliki, won 89 seats for the State of Law party he established for this election, having broken away from the United Iraqi Alliance which, re-branded the Iraqi National Alliance, took 70 seats. The Kurdish Alliance came in fourth with 40 seats.

As Allawi and Al Maliki vie for power, the two other groups have become, in effect, the kingmakers. The National Alliance, of course, has extremely close ties with Iran, where several of its key figures spent decades in exile. Washington meanwhile, having spent $900 billion (Dh3.3 billion), having lost 4,386 soldiers, having caused the deaths of more than a million Iraqi civilians and the displacement of five million more, is obliged to stand back in the interests of democracy whilst the battle for power which is likely to last several months rages on out of its control.

Deploying democracy as a means to secure regime change or to further a hidden agenda is a risky business as Western powers have discovered before the 2006 electoral victory of Hamas in Gaza, for example, or the unexpected landslide obtained by Algeria's Islamic Salvation Front in that country's first free parliamentary election in 1991.

(America's preferred candidate may be morally dubious or even downright corrupt Afghanistan's President Hamid Karzai springs to mind but all that matters, it seems, is that the candidate's accession to power is legitimised through the ballot box.)

Mortifying prospect

But the fruit of last month's Iraqi election now tastes particularly bitter for the US as it contemplates the mortifying prospect of arch-enemy Iran brokering a power-sharing deal, a deal which will almost certainly consolidate Tehran's own close allies' control of the very country America has been seeking to ‘liberate'.

Shortly after the elections Tehran received visits from National Alliance leaders, a delegation from Al Maliki's State of Law alliance and Jalal Talabani, from the Kurdistan Alliance. Indeed, the only major player not to be invited to Iran was Eyad Allawi.

In a bid to resolve the problem internally, Moqtada Al Sadr, leader of the largest party in the National Alliance, organised an informal referendum. Some 1.4 million voted and the results, announced on April 7, saw neither Allawi nor Al Maliki but former interim prime minister Ebrahim Al Jaafari favoured a choice unlikely to be endorsed by any of the other parties.

Al Maliki (whose former militia forms a significant part of the Iraqi army) has threatened to turn to violence in his bid to hang on to power, and the prospect of all-out civil war is once again rearing its ugly head.

The sectarian differences that now inform Iraqi politics continue to weaken the nation's social fabric and the population, already exhausted by seven years of violence, is enduring a new wave of bombings and murderous attacks. Al Qaida, too, is resurgent in Iraq, exploiting the weakened security apparatus produced by the current power vacuum. During the election campaign alone, 228 people were killed.

Divisive as its results are proving to be, this election nevertheless demonstrates a desire among the populace to move away from politics informed by religion. Allawi's Iraqiya ticket, which secured the most votes, was firmly secular and nationalist.

Although he left the Baath party many years ago, when Allawi announced his bid to become prime minister in August 2007, he received an endorsement from its leadership in exile. Speaking to Time magazine, a spokesman described him as "an Iraqi patriot" who would pave the way for the Baath Party to "return to the political life of Iraq, where we rightfully belong".

Plus ça change

Abdel Bari Atwan is editor of the pan-Arab newspaper Al Quds Al Arabi.