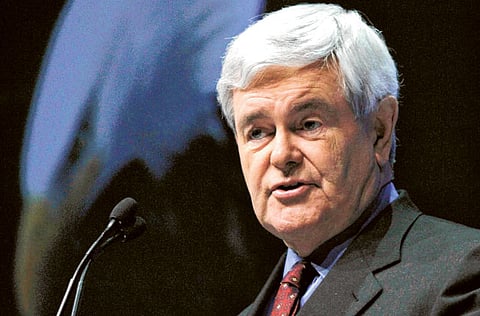

Gingrich's words show his ignorance

By throwing provocative statement about Palestinians into the lacklustre Republican debate, he sought to forge ahead of his rivals

When the Republican presidential hopeful and former US House Speaker Newt Gingrich recently affirmed that the Palestinian people were an invention, he had one thing in mind: scoring cheap points against his rivals. The truth of the matter did not interest him; nor did he show any regard for the impact of such a fantastic proclamation on the suspended peace process, or indeed on his own country’s longstanding policy on the conflict.

By throwing such a provocative statement into the lacklustre debate among Republican presidential hopefuls, he sought to create an environment in which his extremist position would place him far ahead of his rivals. But no one rose to the bait because even the most fanatical supporters of Israel no longer expect such an extremist position as the price of loyalty.

But what Gingrich did not know is that his preposterous proclamation that the Palestinian people are an invention is a perfectly logical metaphor for the conflict over Palestine. That phase of the conflict, however, has already been discredited. One of the most salient features of that conflict was the determination to displace the ‘other’, physically as well as psychologically and intellectually, as a serious competitor for the land.

Displacement was inherent in the daring Zionist project of wrestling a country from its own inhabitants. This much was recognised and advocated by the early Zionist leaders.

Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, observed in his diaries at the end of the 19th century that for the Zionists to take over Palestine from its inhabitants they must “spirit the penniless population across the frontier by denying it employment”. He stressed that: “Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried away discreetly and circumspectly.”

Naturally the Zionists could not say in public that their project to establish a Jewish state in Palestine involved the displacement of the indigenous inhabitants. This would have been, in today’s parlance, politically incorrect. All the more so at the Paris Peace Conference, still wedded to US president Woodrow Wilson’s principle of self-determination.

The Zionist leaders came in strength to the Peace Conference (1919) to make their case for the establishment of a Jewish home in Palestine. The people of Palestine were represented by Prince Faisal, a hesitant figure visiting Europe for the first time, who spoke in Arabic and had no allies or supporters.

The representatives of the Great Powers including British prime minister Lloyd George, UK foreign secretary Lord Balfour, and Wilson himself, were already supporters of the Zionist project. Nevertheless, the Zionist leaders, having displaced the Palestinians as interested party in Palestine, sought to reassure the Peace Conference about their intentions. “What we want,” the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann said, “is a country in which all nations and all creeds shall have equal rights and equal tolerance”.

The reality was different. The Zionists’ modus operandi remained exclusionist, and founded on the denial of the existence of the ‘other’. This was perfectly summed up in the powerful slogan about Palestine being “a land without people for a people without a land”.

When the Zionist Commission came to Palestine it was clear to the Zionist leaders that Palestine was not a land without a people. In fact, Palestine had a developed society and a sophisticated polity. This was recognised by the League of Nations which granted Britain a mandate that recognised Palestine as provisionally independent.

The Zionists in Palestine, who had been arming under the protective cover of the British rule of Palestine, admitted among themselves the necessity of forcibly displacing the Palestinians: “We must expel Arabs,” Zionist leader David Ben Gurion recognised, “and take their places”.

The birth of Israel as a Jewish state in 1948 would not have been possible without the expulsion of 800,000 Palestinians. For decades Israeli propaganda managed to make the West believe that these Palestinians left their homes and country voluntarily at the urgings of Arab leaders. Starting in the 1980s new Israeli historians, using declassified Israeli government papers, documented the expulsion of Palestinians and the birth of the refugees problem.

For decades, the Arab-Israeli conflict was essentially about the Palestinian refugees whom the Arab States wanted returned to what became Israel; and Israeli leaders refused.

Displacing the ‘other’ and denying his existence was not only a Zionist strategy. Arab states myopically engaged in the same strategy. For decades they refused to recognise the existence of the Jewish state. For decades they predicated a settlement of the conflict with Israel on the complete return of the refugees to Israel-which no Israeli government was likely to accept without jeopardising the Jewish character of the country.

The Arab strategy played into the hands of Israeli leaders who continued to deny the right of the Palestinian people to their land. In 1969 Israeli prime minister Golda Meir famously declared: “there is no such thing as a Palestinian people... It is not as if we came and threw them out and took their country. They didn’t exist.”

In 1977, in a dramatic gesture, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat went to Israel, and proclaimed that he wanted to break the cycle of violence and denial. This eventually led to the Camp David Accords in 1978, between Egypt and Israel. But neither Sadat nor US President Jimmy Carter were able to convince Israeli Prime Minister Menahim Begin to recognise the national existence of the Palestinian people. He insisted on describing them as the inhabitants of the land of Israel.

But in the last two decades and especially since the Madrid Conference in 1991 and the Israeli-Palestinian 1993 Oslo Accords the strategy of displacement of the ‘other’ has been discredited.

The Arab states have presented a peace plan based on mutual recognition and UN Security Council Resolution 242 principle of land for peace. The Israelis have not even responded. And although very few people in Israel itself deny the national existence of the Palestinian people, various Israeli governments continue the process of dispossession and expropriation, even as they continue to profess interest in peace.

Gingrich’s strange proclamation that the Palestinian people are an invention only serves to expose his opportunism and ignorance. Somebody should tell him that his worrier services for Israel are behind the times.

Adel Safty is Distinguished Visiting Professor and Special Advisor to the Rector at the Siberian Academy of Public Administration, Russia. His book, Might Over Right, is endorsed by Noam Chomsky, and published in England by Garnet, 2009.