Educating girls is not enough

Education is indeed the first step, but not the only solution

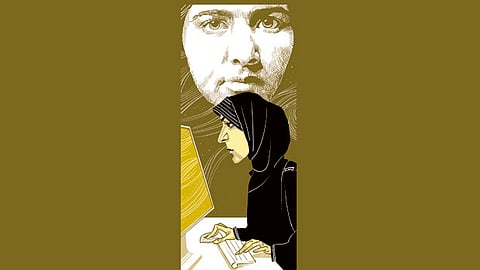

As everyone knows by now, Malala Yousufzai was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, along with Kailash Satyarthi, last week. While Malala was already famous for having been shot at by the Taliban two years ago for her campaign for girls’ education, Satyarthi had been organising peaceful protests and demonstrations against the economic exploitation of children. The Nobel Committee duly highlighted the fact that a Hindu man and a young Muslim woman, an Indian and a Pakistani, were sharing the prize for “common struggle for education and against extremism”. And, to complete the great picture, 17-year-old Malala broke the all-time record as the youngest person to receive a Nobel Prize in any category. Quite an achievement.

There have been voices criticising the choice of Malala, pointing to her political instrumentalisation in the West at the expense of other, less-photogenic activists in the Muslim world. But her courage and eloquence cannot be denied and her becoming a “poster child” for a good cause can only be hailed.

However, But I would like to stress that the education of girls must be seen as the first step in the struggle for women’s rights and powers. Last year, in an interview to BBC, Malala said: “For me, the best way to fight against terrorism and extremism is just [a] simple thing: Educate the next generation.” This statement, while sounding eloquent, is actually counter-productive in two ways: First it implies that the fight is against terrorism, when it really is about the enlightenment of the whole society, even when there is no extremism. Secondly, it presents education as the complete solution to the problem, when it is only the first (major) step. Last year, the World Economic Forum released the Global Gender Gap Report 2013, where 136 countries, including 14 Arab states, were assessed for differences in opportunities for men and women in education and social, economic and political prospects. The report showed that even when countries, such as the UAE, had fully closed the gender gap (no differences in opportunities for men and women) in terms of education, the gap in the rest of social arenas was far from bridged.

Indeed, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Algeria, Oman, Jordan, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia have more women than men in their universities. But when other factors and categories are taken into consideration, the Middle East and North Africa (Mena) region is found at the bottom of the world in women’s attainments. The 14 Arab countries ranked between 109 (UAE) and 136 (Yemen). In fact, the situation seems to have worsened in recent years in some respects. For instance, in Egypt, while the fraction of women in parliament was 13 per cent in 2010, it was only 2 per cent in 2013. Likewise, in the economic sector, 10 of the 14 Arab states occupied the bottom-15 places in the Gender Gap report.

More disturbingly, education does not seem to be solving the problem of the status of women in this part of the world — at least not fast enough. Indeed, university degrees for women do not translate into employment, much less leadership positions. In Egypt, 32 per cent of female university graduates were reportedly unemployed, three times more than men. In Syria, the rates of unemployment in 2011 (before the war) were 71 per cent for women and 27 per cent for men. And in most Arab countries, women get less than 10 per cent of leadership and managerial positions.

Commentators point to particular social norms and factors that may explain these numbers, at least partly: Once women get married and have children, they often choose to stay at home, no matter how high their education level is. Conservative women or families shun employments where women have to interact a lot with men. For example, in Saudi Arabia, while 57 per cent of university graduates are women, only 17 per cent of employed Saudis are female.

Is this worrisome? According to Hatem Samman, director at Strategy&, a global management consulting firm, full employment of women in a given Arab country can raise the gross domestic product by 12 per cent — a very significant increase.

All this points to the importance and necessity of undertaking serious efforts to give women a chance to work if they wish to. Work-from-home opportunities must be increased, especially now that graduates are fully computer literate and digitally connected. Colleges and universities must make greater efforts to reach out to companies to publicise their graduates (men and women) and present to their students the large spectrum of work options that actually exist out there.

At the United Nations Youth Assembly in 2012, Malala made the following statement: “One child, one teacher, one book and one pen can change the world. Education is the only solution. Education first.” Yes, Malala, the teacher and the book can definitely be transformative and education is an important, perhaps the biggest factor in changing lives and societies. Education is indeed the first, but not the only solution. There are additional efforts to be undertaken by society, governments, NGOs and activists. There is more work ahead — for all of us.

Nidhal Guessoum is a professor at the American University of Sharjah. You can follow him on Twitter at: www.twitter.com/@NidhalGuessoum.