Donald Trump’s un-American refugee policy

Where extremists seek to foster a clash of civilisations, democratic governments shouldn’t play into their hands

United States President Donald Trump’s executive order, suspending the entire refugee resettlement programme for 120 days and banning indefinitely the arrival of Syrian refugees is a repudiation of fundamental American values, an abandonment of America’s role as a humanitarian leader and, far from protecting the country from extremism, a propaganda gift to those who would plot harm to America.

The order also cuts the number of refugees scheduled for resettlement in the US in the fiscal year 2017 from a planned total of about 110,000 to just 50,000. Founded on the myth that there is no proper security screening for refugees, the order thus thrusts into limbo an estimated 60,000 vulnerable refugees, most of whom have already been vetted and cleared for resettlement in the US. The new policy urgently needs rethinking.

Refugees coming to the US are fleeing the same violent extremism that America and its allies are fighting in the Middle East and elsewhere. Based on recent data, a majority of those selected for resettlement in America are women and children. Since the start of the war, millions of Syrians have fled not just the military of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad, but also the forces of Russia, Iranian militias and Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant).

There are also thousands of Afghans and Iraqis whose lives are at risk because of assistance they offered to American troops stationed in their respective countries. Of all the refugees that my organisation, the International Rescue Committee, would be helping to resettle this year, this group, the Special Immigrant Visa population, makes up a fourth.

Granting haven to those persecuted for their politics is a core American value. The more than 62,000 Cubans resettled by the committee since 1960 would find this executive order’s denial of refugee needs not just insulting, but bizarre.

The order also suggests that the resettlement programme should make persecuted religious minorities a higher priority, implying that they have been neglected in the past. This is incorrect. Existing law already places strong emphasis on religious persecution among the criteria for resettlement. For example, most of the refugees from Iran — a Muslim-majority country — who are resettled by my organisation are not Muslim.

Compared with other types of immigrants, refugees are the most thoroughly vetted group to enter the US. The resettlement process can take up to 36 months and involves screenings by the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, the Department of Defence, the State Department and the National Counterterrorism Centre and US intelligence community. According to the Cato Institute, the chances that a citizen in America will be killed by a refugee are one in 3.64 billion. An American is far more likely to be killed by lightning than by a terrorist attack carried out by a refugee.

The US can be proud of its wide network of refugee champions, for good reason: Refugee resettlement is an American success story. And this is true not just on the coasts, but across the country. In the 29 cities where the Rescue Committee has resettlement offices, elected officials like the mayor of Boise, Idaho, and the governor of Utah, along with police officers, school principals, faith leaders and small-business owners, actively welcome refugees. They do so out of a sense of a moral obligation, of course, but also because they have witnessed the myriad ways refugees have enriched their communities over the years.

To take one example, over the course of a decade, refugees created at least 38 new businesses in the Cleveland area alone. In turn, these businesses created an additional 175 jobs, and in 2012 provided a $12 million (Dh44.13 million) stimulus to the local economy.

There is a further concern raised by the US president’s refugee ban. When the US abjures its responsibility to the world’s most vulnerable people, it forgoes its moral authority to call upon the countries of Europe, as well as poorer nations like Lebanon, Turkey, Kenya and Pakistan, which host more than five million refugees among them, to provide such shelter.

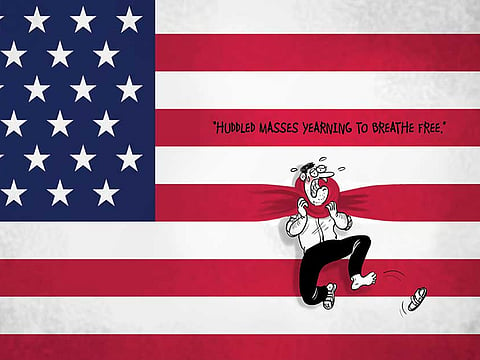

Historically, the US has welcomed the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free”, and this has helped cement America’s leadership of the international order. But why should others continue to bear their heavy burdens when the US won’t? Support for refugees is not charity; it is a contribution to the global stability on which all nations depend — and this is especially important at a time when the world faces a heightened threat of terrorism.

Terrorists are strategic in their work and their messaging. The civilised world must be equally strategic in its response. Where extremists seek to foster a clash of civilisations, democratic governments should not play into their hands. That is what a ban on specific nationalities does. It is not right, it is not needed and it is not smart.

In 1980, when the US Congress passed the Refugee Act with bipartisan support, the then US president Jimmy Carter’s secretary of health, education and welfare, Joseph A. Califano Jr., said the refugee issue required the US to “reveal to the world — and more important, to ourselves — whether we truly live by our ideals or simply carve them on our monuments”.

That still resonates today. Expert review of the resettlement vetting process is part of good government. Hasty dismissal of carefully developed systems is harmful in and of itself. It is also a distressing departure from fact-based policy making.

The world looks to America for enlightened leadership. Its citizens seek the same from their government. Refugee policy is a telling test for every nation. The US passed that test for so many years, so it is a tragedy for it now to fail when its commitment is needed more than ever.

— New York Times News Service

David Miliband, a former British foreign secretary, is the president and chief executive of the International Rescue Committee, a humanitarian aid organisation.