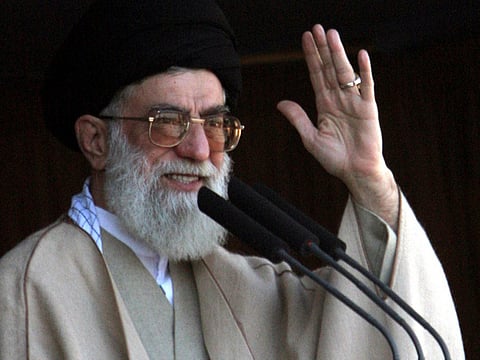

Ayatollah Khamenei’s enormous dilemma

Iran’s Supreme Leader has his reasons for deciding not to politically eliminate former moderate president Al Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani despite the turbulence he creates now and then

Last week, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani fiercely attacked the Guardian Council, the ultraconservative body that vets electoral candidates. Rafsanjani, Iran’s former moderate president, reacted to the Council’s purge of thousands of moderate candidates for the February 26 elections. The Council is composed of twelve members: six Islamic clerics appointed by the Supreme Leader himself, and another six jurists elected by the Parliament (Majlis) from candidates nominated by the chief of the judiciary (who is, in turn, nominated by the Supreme Leader).

Addressing Council members, Rafsanjani asked, “Where did you receive your qualification? Who qualified you? Who gave you permission to judge? Who gave you authority, the right to take all the guns, have all the platforms, Friday prayer platforms, and run state radio and television?”

Many observers viewed Rafsanjani’s remarks as not just an assault on the Council, but also an indirect criticism of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. It is Ayatollah Khamenei who appoints Council members, and the Council’s permission to judge has been entrusted by him.

The “authority to take all guns” is also given to the moderates’ rivals by Iran’s leader, who appoints commanders of the army and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), while the head of state radio and television — there exists no non-state radio and television in Iran — is also appointed by the Leader. Rafsanjani’s statements were unprecedented, as he had not confronted Khamenei since he assumed leadership in 1989.

In his meeting with the members of the Supreme National Security Council, Ayatollah Khamenei indirectly responded. Without giving names, but clearly targeting the moderates, he hinted at “some people in Iran who do not tend to stand against the arrogance”. He urged the country’s Supreme National Security Council (SNSC) “to stand against arrogance and confront those who remain idle to it”.

Although Rafsanjani played a key role in Khamenei’s ascent to supreme leader in 1989, differences between them emerged with the beginning of Rafsanjani’s eight-year presidency (1989-1997). At the heart of their differences was relations with the US. The Leader categorically rejected such diplomacy, while Rafsanjani believed that that approach was unsustainable.

Pressure on the Council mounted when Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, himself a disciple of Rafsanjani’s school of thought, also criticised the Council’s move. To avoid a repeat of the 2009 unrest that followed Mahmoud Ahmadinejad winning a disputed second term, the Council revised the mass disqualification of the moderate candidates on February 6. Rafsanjani was quoted as saying: “The good news for the disqualified candidates is that 25 per cent of them have now been allowed to run in the elections.”

With the emergence of Ahmadinejad in 2005, Rafsanjani — once the second most powerful man, with the Iranian Revolution’s leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, being the first — was pushed to the margins. There wasn’t a day that accusations and attacks were not aimed at him in the media, who supported Ahmadinejad. Indeed, Ahmadinejad, who lacked any identity in Iran’s politics and had no presentable political vision, identified himself as the antithesis to Rafsanjani’s school of thought, which he called corrupt and in favour of aristocracy.

In 2009, following the upheavals, Rafsanjani attempted to capitalise on the dissident movement, vehemently supporting the protesters in hopes of saving his political life. Rafsanjani was not, nor had he ever been, a member of the reformist camp.

Fault lines blurred

Although the movement was heavily quashed, from that point on moderates and reformists shaped an unannounced unity and the fault lines between them were blurred. Rafsanjani’s support of the protesters resulted in a surge of his popularity among the middle-class urbanites who shape a significant political camp in Iran. The group now supports both the moderates and the reformists.

During the 2009 uprisings, Ayatollah Khamenei went public with his differences with Rafsanjani. In a long Friday prayer sermon, he acknowledged some “different points of view” with Rafsanjani and supported his arch enemy, Ahmadinejad. He praised Ahmadinejad as hard-working and said Ahmadinejad’s views “are closer to mine than those of Mr Rafsanjani”.

Rafsanjani’s wounds that the Guardian Council inflicted on him by disqualifying him during the 2013 presidential elections have still not healed. Many observers expected that Ayatollah Khamenei would intervene and ask the Council to reverse its decision. In 2005, after the reformist candidate Dr Mustafa Moein was disqualified by the Council, Iran’s supreme leader asked the Guardian Council to reconsider its decision. Khamenei’s intervention enabled Dr Moein to run. However, despite the shock that Rafsanjani’s elimination created in the country, Khamenei made no move and chose silence.

In the aftermath of the 2009 mass protests, political figures who had supported the “sedition” — the name conservatives chose to identify the upheavals with — were either jailed or lost their positions. Rafsanjani was the only one who remained unharmed, although the conservative assault accusing him of supporting the sedition continues to this date.

In a glaring example, Ayatollah Khamenei reappointed him as the chair of the Expediency Council. The Expediency Discernment Council of the System, as it is formally known, is an administrative assembly appointed by the Leader. It was originally created in 1987 to resolve differences on legislation between the Parliament and the Guardian Council. A constitutional revision in 1989 gave it legal standing as an advisory body to which the Leader could refer regarding significant issues needing resolution.

The move suggested that despite the large gap between the two, Iran’s leader is not yet ready to eliminate the key centrist figure in the Islamic republic. This despite the enormous noise made by ultra-conservatives to confront Rafsanjani. Mohsen Ejei, the spokesman of the hard-line-dominated judiciary, responded to Rafsanjani’s statements by saying: “Those who have insulted the Guardian Council will be definitely confronted even if they are an official.”

There are several reasons behind Ayatollah Khamenei’s decision not to politically eliminate Rafsanjani despite the turbulence he creates every now and then.

First, Rafsanjani is now popular. He is not only popular among the people, but also among the clerics. His popularity stems from the fact that he has been the voice of the dissent since 2009 within the establishment that resists monopolisation of power by the conservatives. But as long as he does not provoke unrest, the system prefers to weaken him, as evidenced by his statements addressed to the Guardian Council, fuming against concentration of power and guns in the hands of the rival group.

Some may argue that the former reformist president Mohammad Khatami was, despite his widespread popularity, silenced with no major cost to the system. But one should not forget that Khatami was not a high ranking old guard within the establishment, elected by the Leader to head an assembly that includes Iran’s political elite.

Second, purging Rafsanjani — a leading figure of the old guard of the revolution — could logically raise serious questions and suspicions about the stability of the system. The radical move could lead to unintended and unexpected developments and consequences both domestically and internationally. And such a move could not stop at purging just Rafsanjani. He has followers, Rouhani included, scattered within different departments of the nezam (the establishment). The system would then be forced into dealing with his followers as well.

Moreover, from a different angle, the establishment needs this moderate current in order to facilitate relations with the West, mainly the US, to reduce tensions and buy time and opportunity to rebuild and restore Iran’s damaged economy. The system now well knows the outcome of the actions of Ahmadinejad, his team, and the hardliner Saiid Jalili who led the Iranian nuclear negotiators, on Iran’s economy.

Now the question becomes how far Rafsanjani is prepared to go in his confrontation with the monopolisation of power by the rival group. If the moderates face a significant defeat in the upcoming elections, will he continue his assaults on the Guardian Council? Wouldn’t such manoeuvring risk the emergence of another uprising with bitter results for the moderates and the country as a whole?

Shahir ShahidSaless is a political analyst and freelance journalist writing primarily about Iranian domestic and foreign affairs. He is also the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace, published in May 2014. He lives in Canada.