Arabs and democratic choice

Egyptians can learn from the Indian model which gives the poor a means to vent their frustration through the ballot

Egypt's fate has had the world riveted in recent days to newspapers and televisions, as the unfolding consequences of Tunisia's Jasmine Revolution seem to portend a wave like the liberal revolutions of 1848 for the Arab world.

Amateur historians ask breathlessly whether this could be the year of decisive change in the Middle East, the year when regime after regime falls prey to rising discontent with authoritarian rulers who have failed to deliver decent lives to their people. Who could be next: Yemen? Libya? Sudan? Even Jordan?

Watching these events from afar, I find it difficult to escape the conclusion that it is not authoritarian rule per se that is being challenged in the streets, much as we democrats would like to believe otherwise; rather, authoritarian rule has simply failed to deliver the goods.

Authoritarian rule has been accepted in each of these countries for decades. What the protesters are shouting for is not just freedom but dignity — the dignity that comes from having a job worth doing, enough food to eat, and the hope of a better life for their children.

The biggest failures of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak and Tunisia's Zine Al Abidine Bin Ali may not have been repressive politics, but failed economics. If young men had not been unemployed and struggling to make ends meet, feed themselves, and be able to offer a home to the young women they desire, they would not be risking their lives and freedom calling for the overthrow of their governments.

And yet one is tempted to ask the question: would a different political approach have avoided regime collapse? In other words, could democracy have provided a sufficient outlet for the grievances of jobless and frustrated youth?

The Indian experience offers an instructive model. Unlike most developing countries — including every country in the Arab world — India, upon attaining its independence from colonial rule, did not choose to adopt an authoritarian system in the name of nation-building and economic development. Instead, it chose democracy.

British rule left India impoverished, diseased, and undeveloped, with an appalling 18 per cent literacy rate. The British-determined partition with Pakistan added communal violence, the trauma of destruction and displacement, and 13 million refugees to this list of woes. India's nationalist leaders would have been forgiven for arguing that they needed authoritarianism to cope with such immense problems, especially in the most diverse society on earth, riddled with religious, linguistic, and caste divisions. But they did not.

They decided, instead, that democracy, for all its imperfections, was the best way to overcome these problems, because it gave everyone a stake in solving them. Democracy reflected India's diversity, since Indians are accustomed to the idea of difference.

Consensus

The Indian idea is that a nation may contain different castes, creeds, colours, convictions, cuisines, costumes, and customs, yet still rally around a consensus. And that consensus is the simple idea that in a democracy you don't really need to agree — except on the ground rules for how you will disagree.

Indian nationalism has therefore always been the nationalism of an idea — the idea of one land embracing many, a land emerging from an ancient civilisation, united by a shared history and sustained by a pluralist political system.

India's democracy imposes no narrow conformities on its citizens. The whole point of Indian pluralism is that you can be many things and one thing: you can be a good Muslim, a good Keralite, and a good Indian all at once.

The Indian idea is the opposite of what Freudians call "the narcissism of minor differences." In India, we celebrate the commonality of major differences.

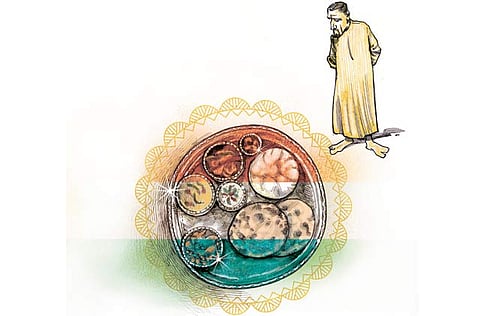

If America is famously a ‘melting pot', then to me India is a thali, a selection of sumptuous dishes in different bowls. Each tastes different, and does not necessarily mix with the next, but they belong together on the same plate, and they complement each other in making the meal satisfying.

Amid India's myriad problems, it is democracy that has given Indians of every imaginable variety the chance to break free of their lot. There is social oppression and caste tyranny, particularly in rural India, but Indian democracy offers the victims a means of escape, and often — thanks to the determination with which the poor and oppressed exercise their franchise — of triumph.

The significant changes since independence in the social composition of India's ruling class, both in politics and in the bureaucracy have vindicated democracy in practice.

The result is that, though economic difficulties — rising food and fuel prices, corruption, and unemployment — persist, they have not led to demonstrations calling for regime change. Indians know that they can use other means — debates in Parliament, political alliance-making, and eventually the ballot box — to bring about the changes they desire.

Democratic accountability also guarantees responsive government. Indian governments act today for fear of electoral retribution tomorrow. That is an incentive that Mubarak and Bin Ali never had.

India has always been reluctant to preach democracy to others. Its own history of colonial rule makes it wary of preaching its ways to foreign civilisations, and underscores its conviction that each country must determine its own political destiny.

Democracy, in any case, is rather like love: it must come from within, and cannot be taught. Nevertheless, for Arab rulers looking uneasily at the lessons of events in Tunisia and Egypt, the example of India might be well worth heeding.

Shashi Tharoor, a former Indian minister of state for external affairs and United Nations undersecretary-general, is a member of parliament and the author of Nehru: The Invention of India.