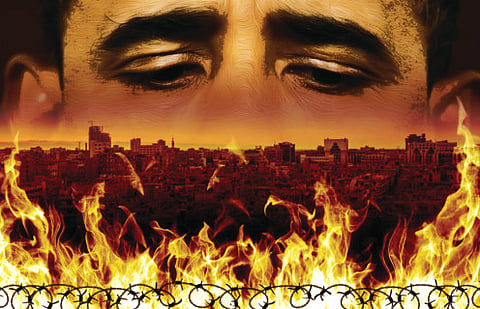

America’s Syria non-policy

What Obama should be faulted for is his failure to articulate his reasons for choosing non-intervention

Russia’s bold entry into Syria’s civil war could end badly for its leadership. But in the Middle East, everyone can lose nowadays. Just as Russia might lose for going in, the United States could lose for staying out — or, more specifically, for failing to design, much less pursue, a coherent, goal-oriented policy in the country.

For better or worse, Russian policy in Syria reflects not just a goal, but also a real strategy aimed at achieving it — a strategy that Russian President Vladimir Putin recently advanced by meeting Syrian President Bashar Al Assad for talks in Moscow. Now that Russia has knocked at least some of Al Assad’s enemies on their heels, the Kremlin has decided that the time has come to discuss forthcoming political arrangements — or, perhaps more accurately, the time has come to tell Al Assad what will happen next.

Unfortunately, US President Barack Obama’s policy lacks the same cohesion. To be sure, much of the criticism that his administration’s foreign-policy choices — for example, the decision to stay out of Syria — reflect weakness or indecision is inaccurate. Such accusations do not reflect reality so much as the tendency — which has intensified during the ongoing US presidential campaign — to use Obama as a scapegoat for the world’s problems.

The critics would do well to recall that, less than a decade ago, the international community was crying out for the US to take more care in deciding when — and when not — to act boldly. And that is precisely what Obama has done in Syria: He has assessed the options and concluded that US interests are not served by intervening on the ground in Syria, as they are by, say, US-led air strikes against Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant).

But there is a difference between choosing not to intervene and lacking any coherent strategy at all. What Obama should be faulted for is his failure to articulate his reasons for choosing non-intervention and to define alternate steps that the US can take to help mitigate the crisis.

To be sure, a major reason for this failure is the lack of consensus not only throughout the government — ask five senators what to do about Syria and you will probably get at least six answers — but also within the administration. Ultimately, however, this state of affairs must be laid at the door of Obama himself — a president who in other areas has demonstrated an impressive ability to recognise a problem’s complexities and chart a course forward.

The administration’s difficulties in Syria emerged early on, with the assumption that Assad would be ousted within weeks of the conflict’s eruption. It was a miscalculation comparable to that of his predecessor, George W. Bush, who launched an invasion of Iraq on the erroneous assumptions not only that Saddam Hussain possessed weapons of mass destruction, but also — and more important — that post-Saddam Iraq would quickly become a stable democracy.

Once it became clear that Al Assad would not go down without a fight, the Obama administration limited its efforts to secure his departure to public shaming — a tactic with a dubious track record when it comes to dictators. And the tactically foolish ban on Al Assad’s participation in any US-led strike against Daesh — not to mention calls for opposition factions to hold provisional elections — is sloganeering, not policymaking.

To be sure, the Syrian crisis is exceedingly complex — so complex that trying to understand it exceeds the American public’s patience. But if there were ever a US president with the capacity to explain its complexities, it is Obama. When that is done, Obama must set a clear path forward — and then follow through.

For starters, Obama could pledge to work with all countries — allies and otherwise — that have an interest in resolving the Syrian crisis. Whatever their differences, these countries’ shared interest in bringing peace and stability to Syria would provide sufficient common ground on which to construct a coherent policy.

Moreover, while the US view that Al Assad should not remain in power may be morally compelling, America’s official policy towards Syria should leave that decision to the Syrian people. Instead of attempting to impose a new Syrian leadership, the US should host a meeting with internally selected representatives to help them draft a constitution and make other political arrangements.

Finally, Obama should promise to continue working with likeminded entities to degrade and destroy Daesh. After all, as long as Daesh fighters are destabilising the Middle East, Syria can never be secure.

Russia has made its choice to intervene militarily in Syria’s civil war, whereas Obama has decided that the US will not compete with the Kremlin by deploying its own troops. But the US does not need ground forces to make a difference in Syria. What it does need is a coherent policy that advances concrete and considered objectives.

— Project Syndicate, 2015

Christopher R. Hill, former US assistant secretary of state for East Asia, is Dean of the Korbel School of International Studies, University of Denver, and the author of Outpost.