Rahul Mishra: the first Indian designer to participate in Paris Couture Week

Mishra’s life story is far removed from the turbo-charged scenes of global fashion

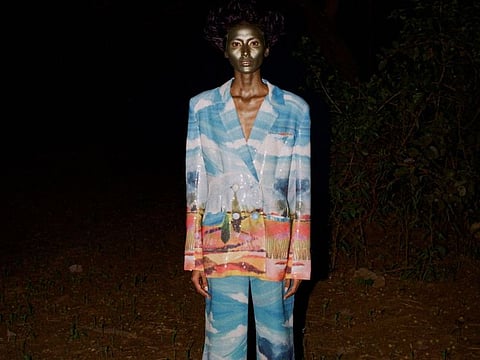

Fashion designer Rahul Mishra has major global ambitions. Since winning the prestigious International Woolmark Prize in 2014, the 43-year-old-designer has consistently shown at Paris Fashion Week. Three years ago, he was the first Indian designer to participate in Paris Couture Week. Mishra’s creations, confections of constructed homage to the natural -world, has won him legions of fans. At the glamourous, high-octane 3-day debut of the state-of-the-art Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Center in Mumbai in April this year, both Zendaya and Gigi Hadid wore his creations.

The French government recently awarded him the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters). Fashion journalist Suzy Menkes has hailed Mishra as India’s ‘national treasure’. At Paris Fashion Week this past October, Mishra launched his newest line, the contemporary label, AFEW (Air, Fire, Earth, Wind), under the aegis of Reliance Brands Limited, a subsidiary of the massive Indian conglomerate Reliance, which have invested in the label.

“A creator’s focus has to be to create pure poetry, something truly beautiful and really original,” Mishra explains. “People try to paint a flower. I am trying to capture the smell of a flower in my embroidery. The challenge is to capture the movement of wind or clouds in our embroidery. My intent is not just to depict an image. We try to capture the movement, the layering, the dew drop, the entire essence of the atmosphere.” Mishra is celebrated for his elevated embroidery, that takes traditional techniques and expands them in vast new directions. He samples designs like a maniac, proclaiming that “if I am failing miserably in my sampling, that’s a good sign. It means I am trying something new. If I achieve samples very quickly, I am relying on a formula. I’ve got to stay away from that.

Every season needs to help us learn five new techniques, shapes, colours or ideas. It’s all about how we can push our creative gondola.” Mishra says he always suffers from design discontent. His ambition is to develop into a brand that matters—not a momentary flash in the pan but one that has longevity. Soft-spoken and thoughtful, Mishra cites the examples of Apple and fashion label Schiaparelli, noting that while Steve Jobs centered all his products around customer experience, Schiaparelli, despite its bespoke size, matters in the realm of fashion. People may not buy anything from the brand, but they pay attention to it. Both put forth a mastery in art and design. Mishra wants to emulate this—a brand with a narrative that makes an impact far beyond its immediate customer base.

Mishra’s own life story is far removed from the turbo-charged scenes of global fashion. He grew up in the small village of Malhausi, near the north Indian city of Kanpur, in Uttar Pradesh. He studied physics as an undergraduate before pursuing a master’s in apparel design from the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India’s most famous design institute.

Mishra was awarded best student designer of the year in 2005. Four years later, he won a scholarship to Instituto Marangoni in Milan, Italy, the first non-European to do so. Mishra is married to Divya, a fellow designer; the two work together. He started his fashion journey in Mumbai, where he worked closely with artisans in Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum. Even as these talented craftspeople created things of beauty, they lived in pathetic conditions. The experience stayed with Mishra. He encouraged his embroiders to reverse migrate back to their villages, where he would provide them with a steady income. “Rather than creating a product just for consumption we try to design a system that creates participation,” Mishra says.

Today Mishra’s headquarters are based in Delhi and he works with over a thousand craftspeople across the country, ensuring them a decent standard of living, in the comfort of their own homes. He points out that “the first ownership of the brand belongs to the weavers and embroiderers.” In fact, Mishra brought master craftsperson Afzal Zariwala, with whom he has worked for more than a decade to Paris Fashion Week, for his most recent show, exposing the artisan’s talents to a wider audience.

“I am not working alone,” Mishra explains. “There are thousands of skilled artisans. Using embroidery in India alone doesn’t make you unique. What makes you unique is how you and your team work together, how an idea that is very personal gets manifested on a garment. ”The idea is to take a dream and make it a common goal to make that one motif, that one flower. This is how magic gets created. We forget what is traditional and what techniques we know because that brings limitations. In this manner, expression becomes limitless. It’s a combination of everyone on the team having their hearts, hands and head aligned in achieving that thing.”

He may call his company a start-up but Mishra has strong global ambitions. His immediate plans includes opening a number of stores in India and to expand his retail footprint internationally, including in the Middle East. “I don’t want to be a moment in fashion, I want to stay and endure.”