Everyday interiors expressed through paintings

How our private spaces from across ages are revealed through art

It is a cliché, but to be a figurative painter is to depict something of the world. Any realistic painting contains a mine of historical, sociological and anthropological information, which the painter himself is not necessarily even aware of. Like all his works, our private spaces are not neutral and exude away of viewing the world, a savoir-vivre and a political stance. Vermeer, in The Music Lesson (1662-1665), owned by the Queen of England, shows a room occupied by two people surrounded by a few refined and made objects. An era in which every acquisition was important and where inventoried possessions left behind after death would fit onto one sheet of paper. The design of the stained-glass windows has a technical explanation. It was very difficult in those days to manufacture large-format glass panels.

Some 220 years later, the piano of the woman in Listening to Schumann (1883) by Belgian artist Fernand Khnopff, seems a little lost in the midst of saturated velour and velvet, plants and especially the ornate gilded fittings. The concentration of the woman listening to the music is in stark contrast to the stifling intimacy of the salon. It even extends to the painting edges. The composition is less classical than it appears. It is not easy to make out the pianist's hand on the left and the ornaments on the side table are indiscernible as they are shown in their entirety.

Khnopff rather foolishly retained the beautiful composition of his original photograph. Édouard Vuillard also makes use of the medium of photography, but, with greater invention, as shown by his wonderful Large Interior with Six Figures (1897). It explodes the classical perspective used by Vermeer, thanks in particular to the multiplication of vanishing points which are clearly visible in the depiction of intertwined carpets. Decorative industrial fabric is born and motifs are printed onto everything. Paper is also produced in abundance and the family office over flows with paperwork. We are at home with bourgeois Parisians, the patriarchy, a taste for the traditional, floral decoration, books on show, a family living within an enclosed world surrounded by their goods fortunes. Is Édouard Vuillard aware of all that his painting tells us? Probably not. Nevertheless, he is amused by the intimate mess of his environment.

At the same time in Denmark, a painter like Vilhelm Hammershøi paints Lutheran interiors with cold light sliding over bare walls, the brilliance of white porcelain, the napes of dishevelled servants. In Switzerland, Félix Vallotton paints his Interior with Woman in Red (1903).

We are voyeurs, viewing the door frame from one door to the next, finally arriving at what must be a bedroom with its bed, and each room has an item of fabric in one corner.

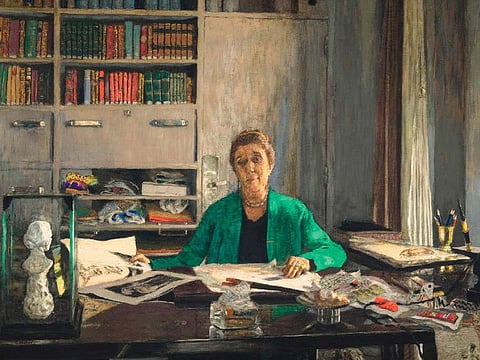

Édouard Vuillard must be the most prolific painter of apartment interiors. He moved away from the Nabis to a much more classical form, passing through a mysterious period thanks to a new ambiance – that of the installation of electricity in the home, which took off in the 1890s. The Belle Époque remains marked by the incursion of nocturnal mysteries, mitigated by the use of lampshades. After the First World War, the inventive painter was blamed for his return to order with a much more realistic style, as revealed by his brilliant portrait of the great seamstress Jeanne Lanvin (1933).

Nevertheless, this work makes reference to all his obsessions: Light shining through space, the independent life of small objects with a predilection for electrical cables, a preference for the depiction of sculptures, windows, the play of brilliance and texture, and his careless humour, with his dog under the desk between the feet of his mistress. The canvas is so fresh and the tastes of Jeanne Lanvin so avant-garde that you would think it a modern-day work. Unlike Edward Hopper, who had painted Room in New York the year before, a cultivated representation of the American way of life, its limits and restrictions clearly apparent, the bored woman. The aesthetics are ultra-dated and the piece could easily be part of the mood board in the Mad Men series.

David Hockney, who had a retrospective at Beaubourg this year, painted Mr and Mrs Clarkand Percy in 1970-71. The portrait still testifies to a certain spirit, the woman stands tall, confident, ready for action, whilst the man slouches in his Breuer armchair. Could such a scene mixing these two genres ever be imaginable before the 20th century? The bell-bottom trousers, like the design of the white Bakelite telephone or the white shag pile rug anchor the painting within a short period. In our ultrafast consumer societies, fashions come and go more quickly and the times are more easily identifiable. Even more contemporary, we see the bourgeois-bohemian lifestyle depicted in the intimate portrait by French painter Michel Castaignet – Christian au salon (2005).

This composition contains an eclectic mix of tribal cushions, industrial lamps, potted plants, an African mask and contemporary paintings, all in a relaxed, white-robed hotel dressing gown, which was no doubt stolen. More bourgeois, the outstanding painter François Boisrond paints his wife Myriem Roussel, embodying Godardian style, languishing in the intimate corner of edges of the bed, evoking the child's curiosity for the "parents' bedroom”. It is impossible not to consider the emancipation of women. The nonchalant eroticism and the focus on reading the news is depicted forever by the feminine figure in Hopper's work. In another of Boisrond’s paintings, more voyeuristic and intimate than Vallotton’s, the stifling room of objects is lit by the light from a screen that illuminates the parquet flooring of the Haussmannian apartment. The round and precise touch of the painter evokes our digital world, but it is the subtle colourist in particular who manages to make us feel the warmth of our all too restrictive personal spaces.

Image credits: J. Geleyns-Roscan/RMN; Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Bruxelles/Musée Kunsthaus Zurich; Royal Collection Trust/supplied; Sheldon Museum of Art