Memories with a dash of thrill

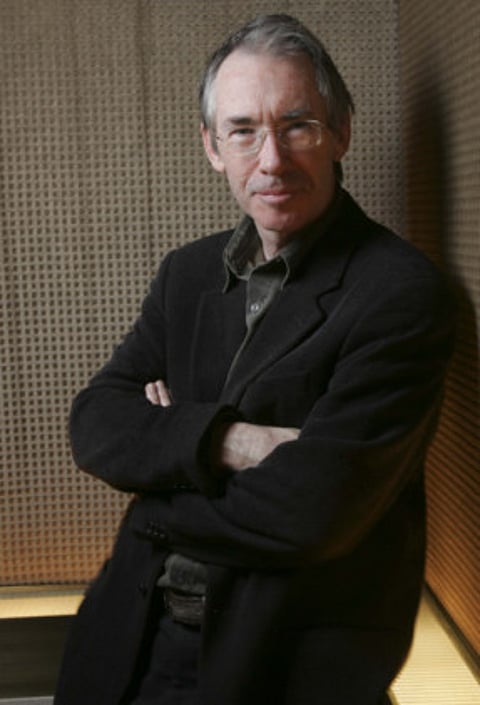

Ian McEwan says his latest, a spy novel set in the Seventies, is a muted and distorted autobiography

Towards the end of his third year at Sussex, Ian McEwan, somewhat reluctantly, visited the university’s careers office. He already knew that he wanted to be a writer, but perhaps, he thought, this could be done in combination with a parent-placating job: “I had read ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’ [by T.E. Lawrence] and the one thing I could imagine being was an Arabist diplomat, the kind of man who would wear a dinner jacket one evening and a keffiyeh the next.”

The careers office gave him a pamphlet. “On the back of it was a table. There were two columns. On one side was your age, all the way up to 65. On the other was your expected salary at any given age. I looked at it and it filled me with horror. My whole life was there. I was going to spend the next 35 years working my way through this table.” The aspiring author’s riding-a-camel-over-a-sand-dune fantasies were thus brought to a sudden and rather feeble end.

Luckily, this was the early Seventies, when it was very bliss to be alive. Honestly! “I had the time of my life,” says McEwan, with a fervent smile. “It was very easy not to have a job, to live the life of a full-time writer. I had a huge apartment in south London and it cost me £3 (Dh17) a week. The occasional review for the ‘TLS’, the occasional piece for ‘RadioTimes’, and I could very easily pay my rent, buy a few books, make a weekly trip to the launderette. There were no machines everyone needed, apart from a hi-fi. I didn’t feel poor at all. At the risk of sounding like Virginia Woolf, I could live on £700 a year.”

But what about the chaos? The piles of rubbish, the power cuts, the bodies left unburied? “Oh, the crises didn’t trouble me at all. I didn’t own anything; I had no stake. I was restless, excited and a touch reckless. I remember reading Daniel Defoe’s ‘A Journal of the Plague Year’. I loved the idea of a city in chaos. There was this line in it that went something like, ‘We walked north out of London in order not to have the sun on our faces.’ I thought: That’s real freedom. I had this ‘let it come down’ feeling.”

There follows a brief pause while he considers what brought an end to this low-level insurrection, and I attempt to match up the Seventies’ McEwan, hair trailing his cheesecloth collar, with the 21st-century version, who is today wearing tastefully crushed pale linen. His task is probably the easier. As he will tell me: “The moment you have children and a mortgage you want things to work; you’re locked into the human project and you want it to flourish.”

For my part, a leap of imagination is required. When I was told my meeting with McEwan would take place in the boardroom of his publisher, Random House, I was terribly disappointed; I wanted to nose round one of his famously lovely homes (preferably the exquisite Fitzrovia terraced house that was the model for the surgeon Henry Perowne’s house in “Saturday”). But now it strikes me as rather appropriate. McEwan is the nearest thing to E.L. James that literary fiction has right now; in this sense, the boardroom chair on which he is uncomfortably perched — it keeps flipping back, forcing his knees up in the direction of his ears — might as well be a throne. No wonder I can no more see him in a launderette than I can picture him watching “The Only Way is Essex”.

Anyway, the Seventies. That is the decade in which McEwan’s new book, “Sweet Tooth”, is set. I can’t say too much about its plot, for the simple reason that it is a novel with a Roger Ackroyd-ish twist and it would be awful to ruin the surprise. But here are the bare bones: Serena Frome is a young Cambridge graduate who finds herself recruited to MI5. An avid reader, she is deployed to work on a Cold War propaganda scheme, codenamed Sweet Tooth, in which government cash will secretly be deployed to fund artists likely to portray the West in a favourable light. One of these artists is a promising young writer, Tom Haley. First, Serena falls in love with his stories. Then she falls in love with their writer. No, she is not a particularly good spy. Her real-life contemporary, Stella Rimington, would have had her for breakfast. (“Sweet Tooth”, incidentally, makes reference to an ambitious colleague of Serena’s called Millie Trimingham.)

How did this curious, beguiling book — a spy novel without even so much as a hint of a poison-tipped umbrella — begin? Which came first, MI5 or the Seventies? “It’s hard to say,” McEwan says. “I rather drift into my novels. For a long time I’ve been interested in the ‘Encounter’ affair [Stephen Spender resigned as the editor of the literary magazine “Encounter” in 1967, after it was revealed that the CIA had been covertly funding it], and I wondered if there was something in there for me; after I finished ‘On Chesil Beach’, which is set in the early Sixties, I thought: Sooner or later I’m going to write about England in the Seventies. So I think it was both. In the end, though, I just took up my green notebook and got Serena to start talking — albeit somewhat against my will.” Why? “Because I’ve got a prejudice against first-person narratives. There are too many of them. They’re too easy; it’s just ventriloquism and authors can hide their terrible style behind characterisation. Any number of clichés are permitted.”

McEwan’s MI5 is a hidebound place, staffed mostly by Pooterish, middle-aged men; filing cabinets are the order of the day, not invisible ink. He was, he says, interested in the idea of institutions and how they grow to have their own weird logic. “What was extraordinary about the cultural Cold War was that the CIA in particular poured millions of dollars into very worthy things — such as a festival of atonal music in Paris in 1950. The idea was to persuade left-of-centre European intellectuals that the West was best and that America wasn’t just mindless and materialist. And when you think about the horrors the Soviet regime produced, you think: why not? But you also think: Why did they do this in secret? Why didn’t the government just use the National Endowment for the Arts or something? It never occurred to them that secrecy wasn’t necessary.”

In the novel, though, his interest in MI5 wavers a little once Tom Haley appears on the scene, perhaps because he and Haley have so much in common. Haley teaches at Sussex University; he is published by Tom Maschler, who first edited McEwan; he does a reading for his first novel with McEwan’s friend, Martin Amis; and two of his stories have been purloined on his behalf from his creator’s backlist. “Yes,” McEwan says. “Well spotted. The novel is a muted and distorted autobiography, though unfortunately a beautiful woman never came into my room and offered me a stipend.”

So what is he saying, exactly? This merging of fact and fiction, and the several duplicities that run through the book, when combined with its passionate accounts of reading and writing, suggest, at least to me, that “Sweet Tooth” is a meditation on the fact that novelists are cunning and cold-hearted thieves; in fact, doesn’t Tom Haley say as much? “Yes. Tom mentions the ruthlessness that is necessary to the process — and it’s Serena’s fear, too, that he’ll write about her.” Graham Greene said that all writers have a “chip of ice” in their hearts. Does he?

“No, I don’t think I do. Philip Roth once said to me years ago, when he took an interest in me as a young writer: You’ve got to write as if your parents are dead. It was very good advice, and I stuck to it, and now I look back with some horror. My father, especially, was torn between exultant pride that I’d published a book and sheer horror at what was in it. So I must have had a steely bit of detachment then. But I’ve never done what Bellow did in ‘Herzog’, or Roth, or Hanif [Kureishi] put their ex-wives in books. I couldn’t do that.” He thinks for a moment. “My chip of ice is a bit slushy.”

Ian McEwan is the child of a soldier: His father, David, was a working-class Scot who worked his way up to the rank of major. He was born in Aldershot and lived first in Germany and then in Libya until, at the age of 11, he was sent to a state-run boarding school in Suffolk. McEwan has said in the past that this was quite a bleak time: “I just went numb for four or five years.” On the other hand, his dorm experiences came in handy when, in 2005, he travelled with the environmental group Cape Farewell to Svalbard in the Arctic — the trip that inspired his last novel, “Solar”. Not for him the chaos of the bootroom. He kept his stuff safely under his bed.

After an English degree at Sussex he went to the University of East Anglia, where he studied for an MA, tutored by Angus Wilson and Malcolm Bradbury. He moved to London in 1974 and became part of the literary set that centred on Ian Hamilton’s “New Review” (Hamilton, like Wilson, has a walk on part in “Sweet Tooth”) and the Pillars of Hercules pub in Greek Street, Soho. It was during this time that he formed some of his most important friendships: with Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and Christopher Hitchens.

Hitchens died of cancer last year. What is the post-Hitch world like? Oh no. He looks so terrible, as pale as ash, I wish I had not asked. “It’s very desolate. It really does feel empty. He was the one of us who seemed to embrace all of literature; as time goes by, I don’t think people will associate him with his taking an unusual line on Iraq. They will connect him with his brilliant essays on writers: Chesterton, Kipling, Wodehouse. The appetite. The conversations. I really do miss them. Martin and I regularly check in with each other in the post-Hitch desert.”

How, though, did he manage to stay friends with them all? The literary world can be envious. Fallouts are standard. “Well, we knew each other before we were known; it’s not as if we are film stars all hanging out together.” Besides, he says, novel-writing isn’t like sprinting. No one needs to come second; there is infinite space for good writing. “And perhaps we’re too old, now, to be jealous. The status anxiety wears off. I like their company. Supper at Julian’s is one of the great pleasures.”

But what if one of them had had to slope off and join a less celebrated profession? “It probably would have changed things, yes. Maybe it was a self-selecting group, though. Who would want to hang out around the Pillars of Hercules? Only those bent by this passion for writing books. We were absolutely determined to become writers. We didn’t use words such as ‘passion’, but we acted them out. Writing was the only important thing.”

His success came a little later than that of Amis. The early macabre books were acclaimed and they had their devoted fans, but I don’t imagine they were big sellers (the first came out in 1975). Then, in 1998, his novel “Amsterdam” won the Booker prize. Nine years later, his 2001 novel “Atonement” was made into an Oscar-winning film, at which point its already considerable sales doubled, even tripled. Does he think success has an effect on creativity?

“Of course it makes a difference,” he says. “But I’ve always done what I want to do, with the result that when I close the door and unhook the phone I feel all the old anxieties associated with trying to get something right.” And there are certain new anxieties. “You worry that sooner or later — it has to happen — you can’t write; that you will become less thought-rich; there is the danger of repeating yourself. All writers in their sixties have to confront these things. When should you stop? Do you tail away with a series of feeble novellas? But in the silence of trying to do it, it doesn’t feel different.”

He is keen to remind me that “Atonement” is an anomaly. “It [having a huge hit] happened once. A couple of books recently haven’t earned back their advances, and the advances weren’t that big. ‘Solar’, since I’m being frank with you, was loathed by the Americans. It absolutely bombed.”

This is no good. If he is trying, metaphorically speaking, to give me a reality-checking cold shower, it isn’t working. His life, from the outside, seems so replete, so purposeful, so — not a word one usually associates with writers — happy. It is enough to make you sick!

He laughs. “Yeah, well, stay with that thought.” And then: “Like lots of people, I made a very good second marriage [to Annalena McAfee, a journalist whom he met when she came to interview him]. We have to learn how to get that right and I take a lot of delight in my sons [from his first marriage, to Penny Allen, whom he divorced in 1995]. I thought it would be bleak when they stopped thinking I was God, but I love the unfolding plot of their early adulthood.” One is a molecular biologist, the other is working in PR.

You can’t necessarily organise how life works out, he tells me. But still, I can’t help but read his own contentment — such peace always involves, I think, a certain amount of effort — as a rebuke to his (now dead) parents. Their marriage was troubled, largely because they were keeping a painful secret: In 2007, McEwan discovered that he had an older brother, Dave Sharp — the result of an affair between his parents when his mother, Rose, was still married to her first husband (Ernest Wort, with whom she had two children, was off fighting in Italy; her baby with David McEwan was born in 1942; Wort died from combat injuries in 1944). The baby was given away via a newspaper advertisement in the “Reading Mercury” which said: “Wanted, Home for Baby Boy, age one month; complete surrender.”

“That would have been my father,” McEwan says. “He would have written that ad. ‘Complete surrender’ — it’s semi-military.” Did he feel cross when he discovered what his parents had done? “Yes. I wanted to shake them. I wanted to say, ‘Confront this; deal with it, make yourselves happy.’ My regret is that they didn’t meet David, because he would have reassured them he wasn’t bitter. One of the first things he [David] said to me was, ‘I was loved as a child.’ He went to visit my mother but she’d already lost her mind. If he’d gone even a year earlier ... ”

It is such a sad story, given that Rose and David eventually married and could have brought up their child together. “Yes. They closed something down for themselves. Probably that was my father too. I can hear him say it, ‘What’s done is done.’ But my parents’ generation it took the sixties for people to give themselves permission to talk about things.”

Is the presence of his brother in his life (Sharp is a bricklayer) another element of his contentment? I think it must be. Even if they’re not best friends, a flashlight has been shone in the direction of yet another shadow. McEwan doesn’t disagree. “It makes life richer,” he says, quietly. “It absolutely does.”

It is a measure of McEwan’s writerly reputation that, even before publication, “Sweet Tooth” is causing a fuss; the Booker judges have naughtily neglected to put it on their longlist. “Oh, I’ve become immune to the Booker,” he says, though this is an easy line to take when you’ve already won it. “I think we need something a little more like the Pulitzer prize, where there isn’t this great race. The sense that it’s a 110 yard dash has a streak of vulgarity about it.”

As for the reviews, he won’t read them. Does he think, as so many people claim, that we are witnessing the end of publishing and, with it, perhaps, the slow death of the novel itself? “We have a hunger for talking and thinking about others and I don’t think any other form can deliver that insider-ish feeling.”

Screen or paper, it doesn’t matter. On the other hand, he has just moved house — yes, Henry’s place has been sold, replaced with a flat in Bloomsbury and a house in Gloucestershire — and he has spent several days pulling books from boxes. “You put them on the shelf and it’s the complete narrative of your existence,” he says. “All these yellowing paperbacks I bought when I was 17. I’ll never read them again, but I could never throw them away, either.” He hugs himself, trying his best — mostly for my benefit — to look neurotic. “I want them around me and that’s not something you can do electronically.”

–Guardian News and Media Limited