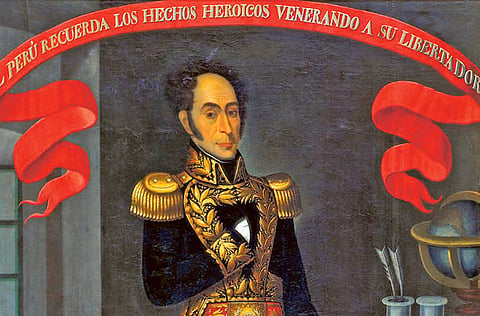

Book review: Bolivar: American Liberator

Simon Bolivar was ruthless in war and blundered as a ruler in peace, yet always stood for liberty and justice

Deep into Marie Arana’s wonderful new biography of Simon Bolivar, “the George Washington of South America”, there is a deliciously unexpected pause in the action. It is 1816, and Bolivar has set sail from Haiti. He is on his way back to Venezuela, with an army set to take on the hated Spanish colonial authorities. At the island of St Thomas, he ostensibly stops for “supplies”. In reality, his fleet of ships has anchored so that Bolivar can pick up his mistress, Pepita Machado. The advent of text-messaging is two centuries away, however, and the lovers have their signals crossed — Machado has sailed for Haiti. For three days, the fleet waits, and when a ship finally retrieves Machado, the flotilla waits one more day while she and Bolivar spend time together.

“Bolivar now maddened his officers with his unquenchable libido,” Arana writes. It was, she adds, a “bad start” to a year of warfare that would see Bolivar proclaim, for the third time, the dawn of a new republic in Venezuela — and fail for the third time to win its war of independence.

In “Bolivar: American Liberator”, Bolivar emerges as a complex and confounding human being. He was the essential figure in the revolutionary wars that created five South American countries. Brilliant and erudite, he was an idealist and also a ruthless military leader as well as a deeply charismatic man of letters.

His speeches and correspondence, Arana writes, “represent some of the greatest writing in Latin America letters” and “changed the Spanish language”. He began his political career as a fervent believer in personal freedom and self-rule. Still, he committed the kinds of atrocities that today would be called war crimes. And he eventually concluded that Latin America was not ready for true democracy.

In Arana’s energetic and highly readable telling, Bolivar comes alive as having willed himself an epic life. As a young man on a visit to the royal court in Madrid, he once played badminton with the future king he would later work feverishly to undermine. As a general, he covered more miles and crossed more mountain ranges, swamps and deserts than Hannibal, Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great — but he spent his final years in obscure poverty.

“Few heroes in history have been dealt so much honour, so much power — and so much ingratitude,” Arana writes. Arana, former editor of the Washington Post Book World, is the author of four books, including two novels and the memoir “American Chica”, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. She brings great verve and literary flair to her biography of Bolivar. Bolivar was born into one of South America’s wealthiest families. But he was also orphaned at a young age and briefly ran away from his court-appointed guardian to live among the street urchins and ruffians of Caracas.

To his good fortune, the young Bolivar found some outstanding teachers in Caracas, including Simon Rodriguez, a follower of Rousseau, Locke and Voltaire. As he grew into adulthood, Bolivar travelled widely. Arana’s account of his journey through 19th-century America and Europe is reminiscent of Ernesto “Che” Guevara’s famous motorcycle wanderings in the 20th century.

In Paris, Bolivar catches a glimpse of Napoleon, socialises with the grand dame Fanny du Villars and meets the legendary naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, personalities Arana vividly brings to life. He hikes the Alps, following the footsteps of Rousseau. In Rome, he meets Pope Pius VII but refuses to kneel and kiss the pontiff’s sandal.

Later, he climbs one of Rome’s hills and looks down at the ruins of the ancient city with his old teacher Rodriguez. Bolivar ponders the failure of the Roman republic and thinks about Latin America’s servitude to Spain.

“Suddenly, eyes bright with emotion, he ... sank to his knees,” Arana writes. At that moment, the 22-year-old Bolivar swore he would liberate his country. Bolivar was only 30 when, in 1813, he first led rebel troops into Caracas, a city he would conquer and lose to the royalists several times during a 14-year war of independence.

Arana’s book is no hagiography. Her Bolivar is brilliant and courageous but also capable of great cruelty. She details the horrors of his early “war to the death” against the Spanish royalists, which quickly devolved into a kind of race war, in which thousands of civilians were executed by both sides.

“Spaniards were being dragged to the dungeons, made to surrender their wealth to patriot coffers,” Arana writes. “The unwilling were taken to the marketplace and shot.”

The revolutionary wars unfolded as an often-dizzying litany of shifting alliances and bloody battles, but Arana describes them all with an eye to the cinematic, her scenes filled with one well-crafted character study after another.

Eventually, Bolivar’s fair-skinned, Creole-led rebels were forced to embrace the cause of blacks and mixed-race people to win their war against the crown. The region’s slaves won emancipation a half-century before their counterparts in the United States.

In the end, Bolivar’s early Latin American democracies failed, primarily, because of the legacy of colonial Spain. To fill royal coffers and keep their colonies weak, the Spanish crown prohibited printing presses and most industry in Latin America. Unlike the New Englanders who created a nation in North America, Spain’s colonies had no experience of local self-rule.

“In his darkest hours, Bolivar wondered whether his America was truly ready for democracy,” Arana writes. His vision of continental unity, of a confederation of Latin American states, fell apart amid the regional conflicts and the power of local caudillos. And in peace, Bolivar badly blundered as a ruler.

“But for all his flaws,” Arana concludes, “there was never any doubt about his power to convince, his splendid rhetoric, his impulse to generosity, his deeply held principles of liberty and justice.”

Bolivar: American Liberator

By Marie Arana,

Simon & Schuster, 604 pages, $35