Obama, Romney tax plans are pie-in-the-sky

Both candidates are unwilling to reveal how the numbers will add up

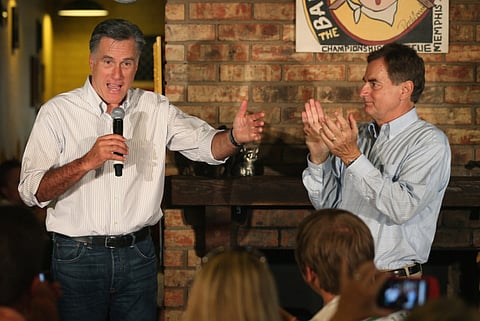

Washington: US presidential elections often produce half-baked proposals. The campaign websites of President Barack Obama and Republican rival Mitt Romney are loaded with 10-point plans to reform everything from education and Social Security to energy policy.

But not their tax plans. Both offer the vaguest of nostrums for the most important issues of our day: What size government do we want? How will we pay for it? And how should the burden be fairly distributed? Rather than engage in serious discussions of such overarching questions, the candidates offer confection.

Romney says he would reduce or eliminate the taxes most of us currently pay. The 2001 and 2003 tax cuts adopted under President George W. Bush? Extend them all. Individual income-tax rates? Reduce them by 20 per cent across the board. Dividends and capital gains taxes? Eliminate them for most taxpayers, and keep the current low rates for those with high incomes.

While he’s at it, the former Massachusetts governor would end the estate tax, repeal the alternative minimum tax, and ditch the higher tax rates enacted with Obama’s health care reform legislation. Here’s the cherry on top: Romney says he would offset the huge revenue losses dollar-for-dollar, and still keep the tax code’s progressivity.

Mathematically impossible

If it sounds too good to be true, that’s because it is. Romney hasn’t said how he would accomplish all of this and still not worsen the deficit or make the tax code less progressive, probably because it’s mathematically impossible.

A Tax Policy Centre study released last week estimates that such a plan — Romney provides so little detail it isn’t possible to precisely score it — would reduce tax revenue from individuals by $360 billion (Dh1.3 trillion) in 2015.

To get to revenue neutrality, Romney’s plan must have an equal amount of reductions in popular tax benefits, including the mortgage interest deduction, the exclusion for employer-provided health insurance, the deduction for charitable contributions, and benefits for low- and middle-income families such as the earned income-tax credit and child tax credit. For Romney’s plan to make sense, taxpayers would have to give up 65 per cent of their tax preferences, the study concludes. Charitably speaking, clawing back that level of tax breaks would be politically difficult.

The analysis also concludes that Romney’s tax cuts would predominantly favour upper-income taxpayers. Those earning more than $1 million would see their after-tax income increased the most, by 8.3 per cent (for an average tax cut of about $175,000). Taxpayers with incomes between $75,000 and $100,000 would see somewhat smaller increases of about 2.4 per cent (for an average tax cut of $1,800). The after-tax income of taxpayers earning less than $30,000 would actually decrease by about 0.9 per cent (for an average tax increase of about $130). It’s no wonder Romney doesn’t want to detail how he would make his numbers add up.

Obama also has a tax plan, and it’s almost as sketchy. It can be summed up as “soak the rich.” In keeping with his pledge not to raise taxes on the middle class, Obama would extend the Bush tax cuts only on income up to $250,000 for married couples. He would increase the top tax rate to 39.6 per cent from 35 per cent and end tax breaks for hedge fund and private equity managers.

Most famously, Obama proposes a Buffett rule, named after investor Warren Buffett, which would require Americans earning more than $1 million to pay an unspecified minimum tax rate.

Millionaire’s tax

The millionaire’s tax would affect about 0.3 per cent of taxpayers, or fewer than 450,000 people. Based on 2009 figures from the Internal Revenue Service, even doubling the tax rate on the richest of the rich would bring in about $190 billion a year, or 1.3 per cent of gross domestic product — far short of the $4 trillion over 10 years that most economists and deficit-reduction panels conclude is needed to keep the national debt sustainable.

Obama hasn’t spelled out where he would find most of those trillions. His 2013 budget plan would raise $206 billion over 10 years by treating dividends, now taxed at 15 per cent, as ordinary income for married couples making more than $250,000 a year. We applaud this idea, yet Obama has done little to build support behind it while campaigning, or to advance it in Congress.

To attack the $15 trillion mountain of publicly held debt, he’ll have to break his campaign promise and go where the money is — the middle class. In 2010, the average federal income-tax rate for a median-income family was 4.55 per cent, according to the Tax Policy Centre. From 1955 until 2007, that rate hadn’t been lower than 5.34 per cent.

Just as Romney must shed his pie-in-the-sky promises, Obama needs to come clean with middle-class Americans by telling them their taxes, now at record-low rates, will need to be raised.