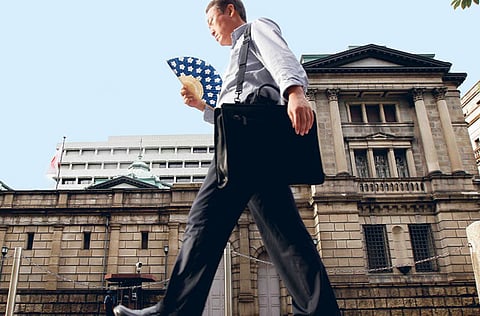

Emerging markets face yen deluge

Japan's currency offloading could likely force rash of capital control measures

London: Japan's yen-selling intervention represents a new headache for emerging markets already battling with huge capital inflows and could set off another round of steps to control the floodgates.

Japan spent an estimated $20 billion (Dh73.4 billion) in a single day of intervention on Wednesday and pointedly did not drain yen funds, leaving extra liquidity in the domestic banking system.

With banks in Japan and the rest of the developed world proving reluctant to lend to businesses and households domestically, this liquidity could eventually leave Japan — where a stagnant economy has kept interest rates near zero for the past decade — in a search for yield.

With borrowing costs in the developed world stuck near zero and speculation of further easing, emerging markets stand out as the top destination.

The resulting impact on inflation would be troublesome for emerging economies, which are generally recovering faster, and where the Institute of International Finance expects to see inflows of over $700 billion in 2010.

Policy tightening measures to curb inflation would attract even more flows, creating a vicious circle.

"A huge pool of liquidity is being created in developed economies and Japan is just another drop in that pool. Ideally you want this liquidity lent out to the domestic economy but some of it will end up in emerging economies," said Michala Marcussen, head of global economics at Societe Generale.

Trigger for controls

She said this could trigger a new round of restriction to capital flows, following those in Latin America in the 1970-80s, in Asia in the early 1990s and emerging Europe in the 2000s.

"We've already seen a couple of policy measures taken by various countries. We could see more. It could potentially lead to a fourth wave of capital controls," Marcussen said.

Fund tracker EPFR data shows emerging equity and bond funds saw inflows of $73.49 billion so far this year, already approaching last year's total inflows of $75 billion.

Brazil, which already imposes tax on inflows, was the first one to threaten more action.

Hours after Japan intervened, Brazil's Finance Minister Guido Mantega said he would not sit on the sidelines "watching the game" while others weakened their currencies at the expense of Brazil.

"We're going to take appropriate measures to stop the real from appreciating," he said. "We're watching every market, every part, for inflows... If inflows come we'll buy it all. We're not going to leave any excess of dollars in the market."

Japanese retail investors already have huge stakes in Latin America, especially Brazil, with one in five polled by Reuters favouring Brazilian stocks.

Brazil has put words into action, calling auctions twice a day to buy dollars in the spot market and increasing the amount it buys. Last Thursday alone, the central bank purchased more than it did during the whole of February.

Next possible steps include an auction of reverse swaps, a form of derivative which has the same effect as buying dollars in the futures market.

Columbia intervened in its market on Wednesday, kicking off a four-month programme to buy at least $20 million a day to help ease the rise of its currency.

Other countries who moved to curb local currency strength this week include South Korea and Thailand.

"It's the latest episode of ... the ‘silent war' which is taking place in global currency markets," said Andre Perfeito, economist at Gradual Investimentos in Sao Paulo.

The International Monetary Fund has endorsed capital controls as a way to curb capital surges, which some economists say have prompted emerging economies to adopt them.

Sovereign fund moves

Instead of stemming it, some countries are exploiting the benefit of capital inflows, using extra foreign exchange reserves accumulated by intervention to create a sovereign wealth fund (SWF). The $3 trillion SWF industry is now seen doubling in less than 10 years.

Back in 2007, China issued 1.55 trillion yuan in special bonds to buy about $200 billion of central bank reserves to create China Investment Corporation (CIC). That sum has grown to $300 billion and the CIC has been lobbying for additional funding.

South Korea plans to inject more than $5 billion into its SWF. Brazil said it could use the SWF to absorb extra dollars from a planned share offering of Petrobras.

Authorities are under pressure to effectively manage reserves, which is essentially national savings, and also maintain financial stability by not taking too much risk.

"One way of squaring this circle is to set up a SWF with a very clear mandate to manage long-term national savings," said Andrew Rozanov, head of sovereign advisory at Permal Investment Management.

Swap option

Rozanov, who coined the term sovereign wealth fund in 2005, suggests a one-off swap of funds between dollar-heavy reserves and national pension funds that tend to have a high home bias.

"[A swap] may be one way to redeploy excess FX [foreign exchange] reserves to be managed more optimally in a more appropriate long-term investment vehicle," he said. "It would also be a sound way to achieve better diversification of national savings and to help monetary authorities shrink reserve assets."

- $73.4b inflows into emerging equity and bond funds this year

- $75b inflows into emerging markets last year