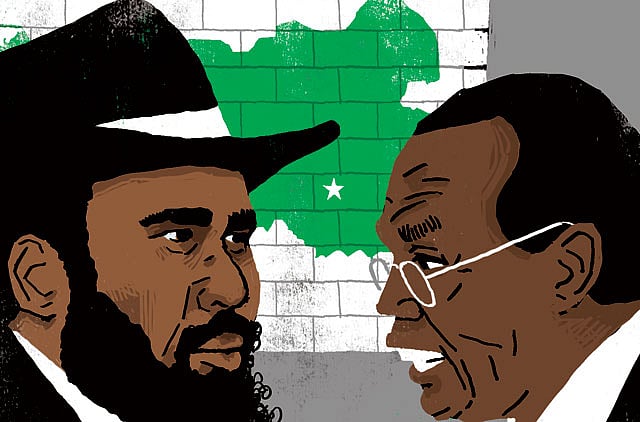

When South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir used a presidential decree in July this year to dismiss his cabinet, including vice-president Riek Machar, many worried that it signalled too clearly the lack of political will to seek compromise over growing political differences within the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) party. When the president appeared on state television on December 16, wearing a full army uniform in exchange for the familiar black suit and cowboy hat, denouncing Machar for having allegedly staged a coup, the country seemed to have moved dangerously close to civil war. Since then, hundreds of people have died in Juba and other state capitals following fighting between opposing Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) factions and other armed groups, with new evidence now emerging of alleged ethnic killings. More than 30,000 South Sudanese are reported to have sought refuge in United Nations compounds, while thousands of others are displaced fleeing the violence across the country. As of December 21, the army’s spokesman Philip Aguer confirmed that the Commanders of the fourth and the eighth division of the army had defected and that the government had lost control over large parts of Jonglei and Unity state.

These events represent the worst crisis South Sudan has faced since independence. The first two years of the country’s existence were overshadowed by a prolonged economic crisis due to the shut-down of oil production as well as tensions with Khartoum over numerous issues including the central region of Abyei and oil transit fees. But the struggle for political power within the ruling party, and particularly between its two top leaders, has been broiling in the background, impeding the government’s ability to effectively address its growing pains.

Kiir’s and Machar’s history dates back decades. Both fought in South Sudan’s decade long civil war with Sudan. Kiir, hailing from the largest ethnic group, the Dinka, rose as a loyal commander through SPLA’s ranks to become the deputy of the SPLM’s founder and former leader John Garang. Machar, from the second largest Nuer community, also fought in the war, yet is known to have switched sides and to have fallen out with the SPLA in 1991. When Kiir took over the SPLM leadership after Garang’s sudden death in 2005, some raised concerns about his political capital and ability to unite South Sudan’s competing ethnic groups.

Ethnic rivalry between the Dinka and Nuer plays an important role in this crisis, yet the unfolding events are symptoms of a deepening political split within the government. According to local South Sudanese observers and media, Machar is not only backed by members of his own tribe, but also by a growing political coalition including the now detained former secretary general of the SPLM, Pagan Amum, a member of the Shilluk tribe, as well as Rebecca Nyandeng de Mabior, the widow of Garang, who himself was a Dinka. When Kiir dismissed Machar and the cabinet in July, many interpreted this sudden move as an attempt to silence growing scepticism of the president’s ability to lead the country.

Building political unity in South Sudan has been no easy task. The country is made up of dozens of ethnic groups, and competition over resources has always been fierce due to decades of war and extreme poverty. South Sudan’s institutions and political processes are still in embryonic stages, and are thus easily bypassed in favour of personalized rule and armed uprising. This most recent crisis presents a major set-back on the country’s slow and difficult journey towards nation building.

Going forward, the main question remains whether Kiir and Machar will resolve their differences through dialogue. In light of the increasing violence, foreign ministers and envoys have been arriving in Juba to urge for a political resolution. Both say they do not want civil war. Yet, there appears to be little genuine interest in finding common ground. Kiir has reluctantly stated that he is ready to sit down and talk. Machar, who has been on the run since the announcement of the alleged coup, has urged for the violence to stop but has commented via social media that “Salva Kiir must leave.”

Even if the two men yield to the pressure of the international community and commence dialogue, it is questionable whether they will be able to achieve true compromise that can mend the current tensions within the party. Furthermore, given the fragmentation of the SPLA and other armed groups, it is uncertain whether such dialogue will lead to an immediate cessation of fighting on the ground. Machar has yet to publicly confirm leadership of the defected armed elements, and it is uncertain to what extent he would be able to mediate a ceasefire.

On the other hand, if the parties do not manage to resolve their differences through negotiation, the consequences for the world’s youngest country could be severe. If politically sidelined, Machar could move to assume leadership of the armed uprising and the country could risk slipping into full-scale civil war.

Continued fighting could leave South Sudan isolated and possibly without much-needed resources. The international community has already moved to evacuate its non-essential staff and US President Barack Obama has warned that the US and other donors will withdraw funding over a military coup. With more than 30 per cent of the government’s budget depending on foreign aid, South Sudan’s already vulnerable population will be left without much-needed basic services and the government will struggle to maintain basic operations.

South Sudan’s oil production can also be at risk if fighting continues. Given that 98 per cent of the government’s revenue comes from the oil sector, all parties understand that control over the oil fields in the border areas with Sudan is of strategic importance. According to the SPLA, much of Unity state, which contains the country’s main oil producing areas, is already under rebel control.

The continued flow of South Sudanese oil via Sudan’ infrastructure is also in Khartoum’s best interest, as the government there is in dire need of the transit fees to fuel its cash-starved economy. If the fighting in South Sudan continues, Sudan is likely to take sides sooner or later to safeguard its own interests, which will further deepen the divide within South Sudan and possibly endanger the implementation of bilateral agreements to bring fragile North-South relations back on track.

Simona Foltyn has a Masters in Public Affairs from Princeton University focusing on economic policy and has lived and worked in both Sudan and South Sudan.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.