Breakthrough mRNA vaccine promises a cure for killer pancreatic cancer

Early trial results suggest tailor-made jabs could stop the deadly disease from returning

The positive results of a new vaccine have raised hopes of a cure for pancreatic cancer. One of the deadliest cancers with limited treatment options, the survival rate of pancreatic cancer patients is abysmally low despite the medical advances of the last two decades. That makes the messenger RNA vaccine [the same technology used to make the COVID-19 vaccines of US firms Pfizer and Moderna] a major medical breakthrough in treating pancreatic cancer.

The vaccine autogene cevumeran produced promising results in a small trial involving people whose cancers were detected early. Half of the 16 patients remained cancer-free 18 months after their tumours were removed and given the mRNA vaccine.

Medical professionals are excited since the results showed that the custom-made vaccine could train the human immune system to kill pancreatic cancer cells by revving up immune cells that target tumours.

This is just the Phase I trial; more extensive trials are required to confirm its efficacy. Yet, considering the high mortality, the vaccine offers genuine hope.

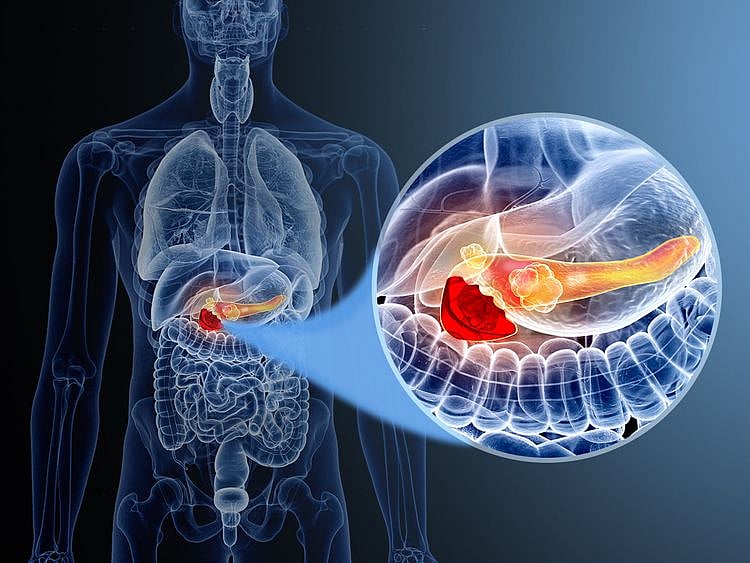

Here’s a look at the pancreas, its functions and how the vaccine fights pancreatic cancer.

What is the pancreas?

The pancreas is a vital organ located behind the stomach in the back of the abdomen, near the gall bladder. Around 15cm long, it plays a crucial role in digestion by producing hormones, including insulin, and enzymes to digest fats, carbohydrates, and proteins.

What’s pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic cancer results from uncontrolled cell growth in a part of the pancreas. There are no early signs until cancer reaches advanced stages. Even at advanced stages, some pancreatic cancer symptoms can be subtle, according to Healthline.

Pancreatic cancer affects more males than females. Although it can occur at any age, pancreatic cancer is more likely to appear after age 55.

What are the types of cancer?

There are two main types of pancreatic cancer: pancreatic adenocarcinoma and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours.

Cancer that begins in the ducts of the pancreas is called pancreatic adenocarcinoma or pancreatic exocrine cancer. This is the most common type.

When cancer forms in the hormone-producing cells (neuroendocrine cells) of the pancreas, it is known as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours or pancreatic endocrine cancer. It is quite rare.

How widespread is this cancer?

Around 460,000 people worldwide are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer each year, leading to nearly 430,000 deaths annually, according to the New York-based Cancer Research Institute.

Some reports say that the number of new pancreatic cancer cases and deaths will double by 2030.

What are the possible symptoms?

Some symptoms that appear in advanced stages include jaundice and abdominal pain. Pancreatic cancer can also affect your blood sugar and lead to diabetes or worsening of pre-existing diabetes.

There are no specific pancreatic cancer symptoms. The disease can cause some of the following symptoms, according to the Healthline and Medical News Today:

What are the causes and risk factors?

The US-based Mayo Clinic, citing a large study, said the combination of smoking, diabetes and a poor diet dramatically increases the risk of pancreatic cancer.

Other risk factors include:

Why is pancreatic cancer so deadly?

Pancreatic cancer is the deadliest common cancer, as 90% of patients die within two years of diagnosis. It is the only cancer with a 5-year survival rate of below 10%. Part of the reason is the late diagnosis. And that results because of the absence of symptoms in the early stages. By the time pancreatic cancer is detected, 70 per cent of people are so ill that it is too late for any treatment, says Chris Macdonald, head of research at Pancreatic Cancer UK.

Currently, only limited effective treatments are available for patients with advanced diseases, especially those ineligible for surgery. “Pancreatic cancer is significantly more resistant to chemotherapy in comparison to other cancer types, leaving patients with fewer options when it comes to treating the disease in its earlier stages,” a report by the Cancer Research Institute says.

Is pancreatic cancer curable?

No, the disease is mostly incurable. But it has the potential to be curable if caught very early. Up to 10% of patients who receive an early diagnosis become disease-free after treatment, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

“Pancreatic cancer is not a death sentence,” says Horacio Asbun, chief of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Surgery at Miami Cancer Institute, Baptist Health South Florida. “While the prognosis is not good, there are new treatments and approaches being done all over the world … For the first time in a decade, we’re making a significant improvement in the overall longevity of patients that have pancreatic cancer,” the US-based doctor told Eat This, Not That! Health.

What’s the new pancreatic cancer vaccine?

The new vaccine is called autogene cevumeran, an mRNA-based individualised neoantigen-specific immunotherapy (iNeST), jointly developed by BioNTech with Roche Group member Genentech. Each vaccine, given by IV drip, is manufactured with mRNA specific to these proteins in that individual’s tumour.

The vaccine will stimulate the production of immune cells (T cells) that recognise pancreatic cancer cells and attack them. Since the T cells are on high alert to destroy cells with these proteins, the risk of cancer returning is reduced after the main tumour has been removed by surgery.

How is the vaccine customised for each patient?

After removing the pancreatic tumour from a patient, it is genetically sequenced to find mutations that produce neoantigen proteins that are alien the body’s immune system. The vaccine is made with mRNA specific to these proteins in the patient’s tumour, a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center report says.

After the vaccine is administered to a patient, it stimulates the immune cells to make the neoantigen proteins. The immune cells train the rest of the immune system (including T cells) to recognise and attack tumour cells that have the same proteins.

With the T cells on the look out to destroy cells with these proteins, the cancer may have less chances of returning, the report adds.

Is it a vaccine or a cure?

A vaccine’s job is prime the body’s immune system to fight a particular disease. Autogene cevumeran is a vaccine, because it aims to prevent the return of pancreatic cancer. The vaccine is administered after the cancerous part of the pancreas or the tumour is removed through surgery. This is to prevent the cancer from returning, which is why it is called a vaccine.

What are the results of the Phase 1 trial?

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center researchers, led by surgeon-scientist Vinod Balachandran, collaborated with BioNTech to develop the vaccine.

In the Phase 1 trial, 16 people were given the vaccine nine weeks after surgery to remove their tumours. There was no effective immune response in eight as cancer returned. But the vaccine elicited a good response in the other eight, and they continued cancer-free 18 months later.

The results of the groundbreaking trial were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology conference in Chicago in early June.

What do the vaccine results mean?

The Phase 1 trial is very small. More extensive trials with more people and longer duration will be needed to confirm the vaccine’s efficacy. More importantly, the Phase 1 trial included only people whose cancers were diagnosed and detected early enough to remove tumours. Only 10% of people are diagnosed with the disease at this stage, Chris Macdonald, head of research at charity Pancreatic Cancer UK, told the New Scientist. So it’s far too early to say whether the vaccine will be able to help people with more advanced pancreatic cancer.

The participants in the trial were also given chemotherapy and received a drug called atezolizumab (a checkpoint inhibitor), the New Scientist quoted Macdonald as saying. Some cancers prevent the immune system from attacking them, and checkpoint inhibitors block that signal, effectively releasing a natural brake on the immune system.

Will the vaccine keep cancer away?

It’s too early to say since more extensive trials are required to know that. The New Scientist report says: “If some cancer cells survived the combination treatment, they could evolve to resist the immune attack triggered by the vaccine. This is the reason why many tumours initially respond to treatments, but then evolve resistance.” That’s the risk with every cancer type, according to Macdonald.

When will the vaccine be available?

A vaccine will have to undergo several trials before approval from regulatory bodies. The pancreatic cancer vaccine has been only through Phase 1 trials. More trials are needed to confirm its efficacy.

Because the survival rates for pancreatic cancer are so low, regulators are likely to accelerate the approval process if larger trials are successful, the New Scientist report says.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.