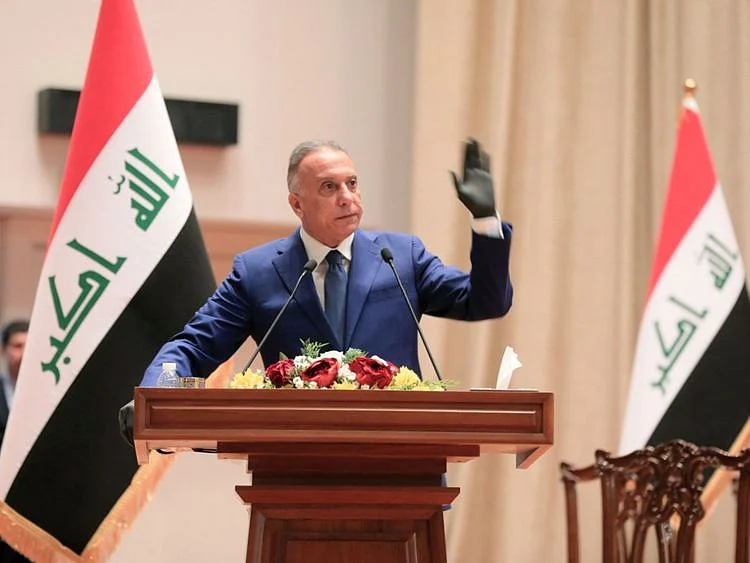

When Mustafa al-Kadhimi became Iraq’s prime minister on May 7, after five months of political deadlock in Baghdad, I argued his best chance of success was to fail fast.

The only way to clean the Augean stables of Iraqi politics was with the strong broom of a popular mandate — and that could only be obtained from elections. Thoroughgoing political and economic reforms would require a majority — or at least a plurality with which to build an irresistible coalition — in parliament.

Last week, the prime minister called for early elections — on June 6, 2021, a year ahead of schedule. But Iraq’s circumstances have deteriorated so much in the three months since he took office, Kadhimi will have a much harder time convincing Iraqis to give him a mandate to rule.

All the crises he inherited have deepened. The coronavirus pandemic, already alarming when Kadhimi was sworn in, has since only grown more frightening, forcing him to announce fresh lockdowns.

Extensive collateral damage

The Iraqi economy, having suffered extensive collateral damage from the oil war, has weakened. Powerful, Iran-backed militias have grown more brazen. Corruption, already ingrained in the body politic, seems to have metastasised across every aspect of the state.

Even the weather has been worse than expected. Iraq is now wilting in the hottest summer ever recorded, with temperatures nearing 52 degrees Celsius (125 Fahrenheit) in Baghdad and 53C (127F) in Basra last week.

The heat threatens to bring the protests against electricity and water shortages — a summer fixture in the Iraqi political calendar — to a fever pitch. Some demonstrations in Baghdad have already boiled over into clashes with security forces: Two protesters were killed last Monday.

Also Read

Iraq PM: Early elections to be held next JuneIraq raids pro-Iran militia accused of attacking US forcesIraqi hospitals become nexus of infection as coronavirus cases rise dramatically among doctorsIraqi extremism expert Hisham Al Hashemi killedGoverning Iraq through the next 10 months will present a series of Herculean challenges for Kadhimi. The first will be to get parliament to agree to the new election date. The political elite is thoroughly discredited and few parliamentarians have any hope of being reelected, so they will want to cling to their positions and privileges for as long as possible.

Not only must Kadhimi persuade a rafter of turkeys to vote for Thanksgiving, he also needs them to sign off on the roasting recipe: A new electoral law, whose broad contours were approved late last year, needs to be finalised before the vote.

Making lawmakers accountable

The law would allow Iraqis to vote for individual candidates rather than party lists. It represents the best hope for making individual parliamentarians more accountable to voters.

Likewise, Kadhimi needs parliament to approve a new election commission and to fill positions in the federal court that ratifies election results.

Plenty of lawmakers who have a stake in the current dysfunctional system will want to delay these changes. So too will Iran, which has a vested interest in perpetuating sectarian politics in order to preserve dominance in Baghdad. On the other hand, the US wants an end to Iraq’s sectarian system, but it has little leverage in parliament.

The prime minister has neither a strong political organisation to support him, nor a well-armed militia at his command. He has not been able to rally the country’s other powerful political force — the popular protest movement that brought down his predecessor — behind him.

An establishment figure

The protesters, most of them young Iraqis with little or no recollection of the Saddam Hussein era, are deeply suspicious of the political elite — and Kadhimi is very much an establishment figure.

By calling early elections, he has met at least one of their demands. The others, including improved government services, more jobs and less corruption, will be much harder to deliver.

The protests will likely grow if Kadhimi doesn’t address the electricity crisis. Fatih Birol, the head of the International Energy Agency, has warned that the power outages, combined with the economic downturn caused by low oil prices, threatens Iraq’s political stability.

But solutions cost money, and the Iraqi government’s revenue shortfall is no less acute than its power shortage. The global economic slowdown caused by the coronavirus pandemic has greatly reduced demand for oil, which means prices are unlikely to rise anytime soon.

Finance Minister Ali Allawi has said that revenues from oil have fallen to $3 billion a month, compared with $7 billion a month last year, forcing the country to seek help from the International Monetary Fund.

That IMF assistance can’t come fast enough. The government, far and away the country’s largest employer, is struggling to pay wages.

Caught between a fretful civil service, a fractious political class and a restive population, Mustafa Kadhimi can expect little respite in the 10 months ahead.

Bobby Ghosh is a columnist. He writes on foreign affairs, with a special focus on the Middle East

Bloomberg

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.