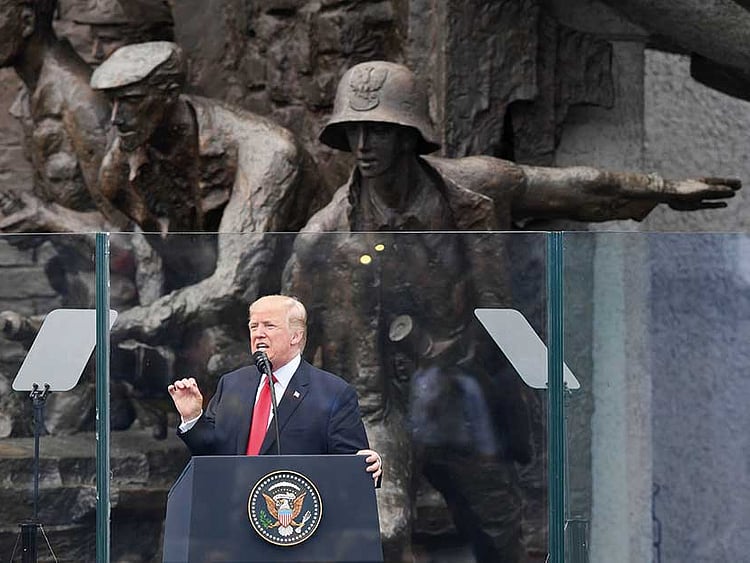

Trump’s defeat will not end populism in Europe

Continent needs immigrants for its economy but accepting immigration has become volatile

The victory of Joe Biden in the US presidential election has brought some hope of not only the revival of trans-Atlantic relations but also, the possibility of right-wing populism losing its momentum in Europe but no one should forget that the right-wing populism has thrived in Europe much before the Trump phenomenon in the US.

Populism is in simple terms is a philosophy that abhors pluralism. In 2016, the year in which the US elected Trump as its President, as a Pew survey had found out, while 58% of Americans thought that many different ethnic groups make a country a better place to live, in Europe only 22.8 % of the population held similar views. In 2018, a survey conducted by the European Commission found 40% of Europeans view immigration as a problem, not an opportunity.

Also Read

America will lead the world again under Joe BidenWhy water war is a big myth US Elections 2020: A new American president in two daysHow Abiy Ahmed can bring back peace to EthiopiaThe world is presently going through a third wave of large-scale human migration. In that first wave up to 1914, nearly 10 per cent of the population of the world moved from one country to another, mostly from one continent to another. The second wave of human migration started after the Second World War, caused by massive destruction and the redrawing of state boundaries, particularly in Europe.

The present and third wave is a combination of both voluntary and forced migration composed of a large section of the world population. In this wave, many more are not only migrating to other countries in search of jobs and better livelihood, but they are also moving in significant numbers to newly developing regions and transition economies in Europe.

Huge inter-regional migration

According to International Organisation for Migration, the total number of international migrants increased from 150 million in 2000 (2.8% of the world’s population) to 272 million persons in 2019 (3.5% of the world’s population). Europe alone hosts 82 million of these international migrants. A large number of people are not only migrating to Europe but also the region is experiencing huge inter-regional migration. In 2017, more than 22 million persons were living in one of the EU member states with the citizenship of another member state.

Migration to and within Europe however is not new. Several Western European countries had accepted large numbers of immigrants in the post-Second World War period. But, the migration in recent years has led to ethno-nationalist mobilisation by right-wing populist leaders that the continent hadn’t been witnessed before.

For more than a generation, Europe’s political elites had settled into a consensus on the issue of immigration. Their uniformity on these fundamental matters had kept the dissenting voices to the political fringe. However, in the last five years, this fringe has become increasingly mainstream. The so-called ‘Migration Crisis’ in 2015 has significantly changed the political reality across the European Union, between and within countries. In many European countries, the rise of right-wing populism has been fuelled by an anti-immigration political mobilisation based on the perceived or projected negative influence immigrants may have on their native ‘culture’.

Europe in a dilemma

Many new leaders have become popular in Europe by promising to protect their nationals against the ‘invasion’ of refugees and even other Europeans. However, Europe is in a dilemma; on the one hand, it needs immigrants for its economy but accepting immigration has become politically volatile.

As an eight-country survey in Europe in late 2017 suggests, the major concern about immigration among Europeans is whether immigrants would adopt their country’s customs and traditions. The identity of European countries is presumed to be altered by the change in the composition of the population due to the influx of immigrants. As an outcome, immigration is increasingly being framed by the populists as one of the main factors weakening national tradition and societal homogeneity.

As the populist parties in Europe use the threat to the ‘European way of life’ as a major tool to mobilise support, several studies in Europe find populists are more successful in the areas receiving low-skill immigration and failing in the localities with high-skill immigration. However, not only the economy of the present but also the uncertainty of the future influences the growth of populism.

The uncertainty about immigration’s impact on state capacity to ensure its citizens’ security and interests also acts as the driver of right-wing populist sentiments. Uncertainty makes the native Europeans believe it would be more prudent to overemphasise hypothetical threats linked to immigration and to prepare for the worst-case outcomes, which works for populists’ advantage.

Migration-fuelled populism

Migration-fuelled populism is not only a concern for individual member-state but European unity. Due to the UK’s Brexit mess, there is increasing support recently for the EU among the European public but at the same time, each European country becoming more patriotic, Xenophobic, and isolated. Many of them continue to disagree on how many immigrants to accept and how to settle them. The populist politicians and political parties have seized on the issue as the major mobilising agent for their political cause.

In the last five years, while left-wing parties in Europe have witnessed a massive drop in their support bases, right-wing populists have not only increased their popularity significantly but also many centrist parties have embraced populism. Populists are surging ahead in many countries like Belgium, Finland, Finland, Germany, The Netherland, Spain, and Sweden. Though the populists in Western and Northern Europe are still forced to operate under the robust democratic framework of the country, the countries in Eastern Europe like Poland and Hungary have not been so fortunate.

Trump’s departure will have a very limited impact on growing populism in Europe. With the increasing number of population migration, the Covid-19 pandemic has also brought a serious economic crisis to Europe. As the previous trends suggest, this will offer a fertile setting for right-wing populism to grow and prosper in Europe in the coming years, even without a Trump occupying the White House.

Ashok Swain is a Professor of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University, Sweden.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Network Links

GN StoreDownload our app

© Al Nisr Publishing LLC 2026. All rights reserved.